download the primer

Key Findings

The Carsey School of Public Policy’s Granite Guide to Early Childhood series highlights issues surrounding early care and education in New Hampshire by synthesizing evidence on a set of interconnected topics. This primer focuses on the cost of child care for New Hampshire families. For more detail about the series, including its other featured topics, visit this link.

Child Care Prices Top $32,000 in New Hampshire

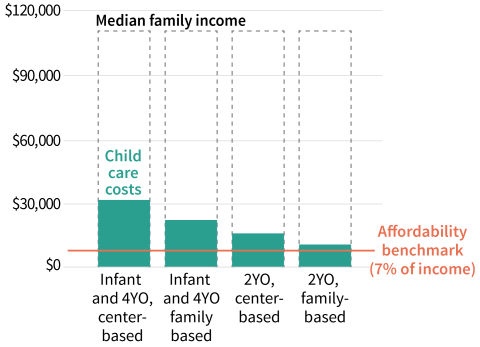

In 2023, the average price of full-time, center-based care for an infant and a four-year-old in New Hampshire was nearly $32,000 a year. Equivalent to 28 percent of median family income for New Hampshire households with children under 5 ($112,230),1 this is four times the 7 percent threshold that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has deemed affordable. At current prices, a New Hampshire family with two young children would need to earn $455,257 a year for the average price of early care and education (ECE)2 to remain “affordable.”

As is true nationwide, New Hampshire child care prices have risen substantially over time. For Granite Staters, the price jumped 48 percent between 2013 and 2023, with a meaningful uptick post-pandemic.3 Consistent over time, however, is variation in price by setting and age, with center-based care typically costing more than family-based care, and care for younger children more expensive than care for older children. Costs also vary within the state; the 2021 and 2024 Market Rate Surveys found that rates are highest in the southern and eastern parts of the state, and lowest in the north.4

Source: Child Care Aware 2024 and author analysis of American Community Survey (ACS) 2022 5-year estimates for New Hampshire. Note: Median income is calculated among families with children under age 5 in the household.

Affordability Is a Challenge for All, but High Costs Perpetuate Inequity

Families struggle to afford child care statewide. Although not necessarily representative of all families, respondents to three different New Hampshire Preschool Development Grant (NH PDG) Family Needs Assessment surveys (2020, 2021, and 2022) named affordability as their biggest child care challenge. Costs may prevent families from enrolling altogether; although little state-specific data exist, evidence suggests that low-income families in New England and nationwide are less likely to use child care than their higher income counterparts. Research through the state’s Early Childhood Equity Movement describes the tradeoffs Granite State families make as they try to balance ECE with other critical bills amid lower incomes.

There is also some evidence that the pressures of unaffordable care disproportionately disadvantage families of color. Research from the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston found that capping child care costs at 7 percent of income would reduce poverty rates, but especially among Black and Hispanic New Englanders. Data on child care affordability in New Hampshire by race is limited.

High Cost of Child Care Fuels Difficult Decisions

Evidence suggests that families face difficult decisions amid a shortage of affordable ECE options. Census Bureau data suggest that in early fall 2024, nearly 16,000 Granite Staters were not working because they were caring for a child who was not in “school or daycare,” a number that has been relatively stable for the last few years. Although some families stay home with children by choice, others’ labor force activity is constrained by child care. For instance, national research finds that about one-third of low-income families left or lost a job due to inadequate child care in 2021.

For families who cannot exit the workforce (often including single-caregiver families), high ECE costs mean adults must contend with less-than-ideal options. Research in the Upper Valley of New Hampshire and Vermont suggests that families cope by using fewer days or hours of care or opting for a different arrangement than they preferred. The same research found that more than half of the Upper Valley’s working-parent sample wanted more child care than they had, and that the most common limiting factor was cost.

Scholarship Program a Key Support, but Can’t Fully Relieve Financial Strain

Perhaps the most important relief from high ECE costs is the New Hampshire Child Care Scholarship Program (NH CCSP), available to families with incomes below 85 percent of the state median (about $113,000 a year for a family of four in 2024). Yet prices are often unaffordable for families who are ineligible for the CCSP, particularly those just out of range of eligibility, part of a persistent national pattern too. Without an alternate federal or state investment mechanism, relief for families ineligible for the NH CCSP is largely limited to ECE providers charging families less than the actual cost of operating so that families in their area can afford to enroll their children. As a strategy for aiding families, this approach is unsustainable, deepening the sector’s economic fragility and reducing resources available to its workforce.

About the Authors

- Tyrus Parker is a research scientist at the Center for Social Policy in Practice at the Carsey School of Public Policy.

- Jess Carson is the director of the Center for Social Policy in Practice and a research assistant professor at the Carsey School of Public Policy.

Acknowledgments

This series was made possible through generous funding and partnership from the Couch Family Foundation.5

© 2024. University of New Hampshire. All rights reserved.