download primer #3

Key Findings

The Carsey School of Public Policy’s Granite Guide to Early Childhood series highlights issues surrounding early care and education in New Hampshire by synthesizing evidence on a set of interconnected topics. This primer focuses on New Hampshire’s child care workforce. For more detail about the series, including its other featured topics, visit this link.

New Hampshire’s early care and education (ECE) workforce operates within an intricate system of standards, credentialing requirements, and quality rating systems, as is true nationwide.1 Yet, even with these stringent requirements, the workforce remains substantially underpaid, and when adjusted for the cost of living, New Hampshire child care workers have the second-lowest wages in the country. Despite high job satisfaction and finding their work rewarding, many also feel burnt out and don’t expect to stay in their jobs. These challenges lead to high turnover and workforce shortages in the ECE sector, jeopardizing the state’s ability to meet family needs.

Granite State Child Care Workforce Is Well Educated but Undercompensated

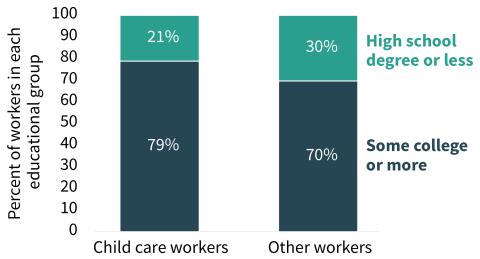

Child care workers in the Granite State are well educated. Seventy-nine percent have at least some college education, compared to just 70 percent of the general workforce (Figure 1). Child care workers are more likely than those in other occupations to graduate from high school and go on to college, though they are somewhat less likely to hold a bachelor’s degree.

Source: Author analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2018–2022. Notes2

Despite their high educational attainment, New Hampshire’s child care workers have low earnings. Census Bureau data used here show the median annual salary among early educators working full-time is $29,185, compared to $58,923 for Granite Staters in other occupations (Figure 2). Further, more education does not translate into higher earnings for child care workers like it does for other workers. Child care workers with some college earn less than 1 percent more than child care workers overall. In contrast, those in other occupations experience a 14 percent premium for some college. Although the child care workforce is younger than workers overall, these differential returns persist even after accounting for age.3

Source: Author analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2018–2022. Median earnings are reported in 2022 dollars. Notes.4

Underpaid Child Care Workforce Reveals and Compounds Sector Challenges

Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that short-order cooks have the closest average salary to child care workers; animal caretakers earn almost five percent more.5 The mismatch among pay, education, and job responsibility reveals a structural issue: individual workers earn so little because child care providers’ main revenue comes from tuition paid by families, and those families cannot afford to pay more.

Unsurprisingly, the sector faces workforce shortages, a higher-than-average turnover rate, and is unable to operate at full capacity. If a child care worker were to purchase center-based care for their own infant and four-year old, this expense would utilize 98.6 percent of the average New Hampshire child care worker salary.6 New Hampshire, like the rest of the nation, faces a challenge, as families pay too much and early educators earn too little.

Appropriate Compensation for Early Educators Is Key for Addressing Sector Woes

A low-paid child care workforce is not unique to New Hampshire. Nationwide, one-third of child care workers were food insecure in 2020, and about half of child care workers participating in the 2020 New Hampshire Preschool Development Grant (PDG) needs assessment worried about paying bills. About one-quarter of PDG respondents who planned to change jobs said they would do so to secure better-paying positions. Nationwide, 16 percent of child care workers do not have health insurance.

An underdeveloped state data infrastructure, while not unique to New Hampshire, precludes a basic workforce portrait. However, Census Bureau data reveal that 90 percent of New Hampshire’s child care workers are women, and 41 percent have children.7 The occupation’s low wages not only reinforce gender-based pay inequities, but also limit care options for early educators’ own children. National data also suggest that pay within the sector is uneven, worse for educators of color and those working with the youngest children. Recently, efforts to address pieces of the challenge are emerging in New Hampshire, including legislation to expand child care scholarship eligibility among child care professionals. Continued efforts to address workforce inequities will be essential for the future of New Hampshire’s early care and education ecosystem.

About the Authors

- Rebecca Glauber is a professor of sociology at the University of New Hampshire.

- Jess Carson is the director of the Center for Social Policy in Practice and a research assistant professor at the University of New Hampshire’s Carsey School of Public Policy.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by New Hampshire’s Preschool Development Grant, sponsored by the Administration for Children and Families (Award# 90TP0110). Additional project support was provided by the Couch Family Foundation.8

© 2024. University of New Hampshire. All rights reserved.