Key Findings

The Carsey School of Public Policy’s Granite Guide to Early Childhood series highlights issues surrounding early care and education in New Hampshire by synthesizing evidence on a set of interconnected topics. This primer focuses on New Hampshire’s “supply” of child care. For more detail about the series, including its other featured topics, visit this link.

Child Care Centers: Predominant Portion of New Hampshire’s ECE Supply

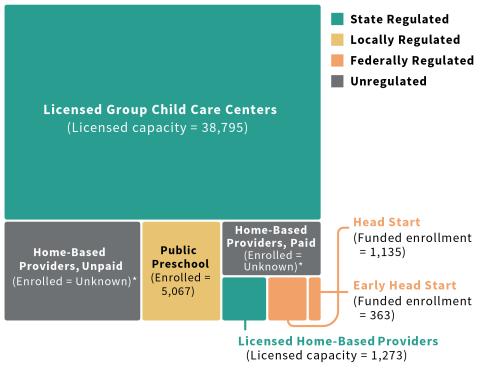

New Hampshire’s early care and education (ECE) landscape spans a variety of settings (see Figure 1). Most of the state’s child care for children under age 5 is supplied by 646 licensed child care providers, largely (83 percent) licensed child care centers.1

New Hampshire’s ECE offerings are regulated to different degrees. Along with licensed child care centers, the state also oversees a smaller set of licensed home-based providers. Some local school districts offer preschool programming, primarily serving children with disabilities with IDEA Part B funds and locally raised supplemental funds, serving about 5,000 children statewide. About 1,500 Head Start and Early Head Start slots round out the state’s regulated offerings.2 In addition, two types of unregulated home-based care meet family needs, including providers who are unlicensed and unpaid (e.g., relatives) and providers who are unlicensed but paid (e.g., license-exempt providers, babysitters).

However, total regulated capacity does not necessarily represent the number of children using that kind of care, nor its true availability. For instance, in 2023, New Hampshire Head Start served fewer children than the number of funded slots. Additionally, many licensed providers face workforce constraints that prevent them from filling all available slots. The Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated these issues, causing temporary closures and lasting impacts on child care availability. Data from 2021 suggests that one-in-three of New Hampshire’s licensed slots was unfilled.

Source. Author analysis of 2024 New Hampshire Child Care Licensing Unit data; 2024 NH PDG Preschool study; 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education; and 2023 Office of Head Start Program Information Reports. Notes.3

A Geographic Consolidation of Slots

Between 2017 and 2024, New Hampshire’s licensed child care capacity increased by 5.6 percent, while its count of licensed providers shrunk by 13 percent. This mismatch is attributable to the greater rate of closure among home-based providers, part of a larger trend in New Hampshire and nationwide. About one-in-ten New Hampshire households with children under age 5 use regulated home-based care,4 making this an important option for families. Whether by choice or constraint, home-based care can fill gaps left by centers, often offering care in more rural places, communities of color, and immigrant neighborhoods, as well as care for lower income families and families with infants and toddlers. Home-based providers tend to offer more flexible and non-traditional hours, and care that is culturally congruent with the families they serve.

While available slots didn’t shrink like provider counts, families now have fewer choices and longer distances between providers. In 2017, providers serving children under 5 were located in 182 New Hampshire zip codes. By 2024, this fell to 173 zip codes, with closures disproportionately impacting less-populous zip codes.5 While families don’t necessarily need care in their own zip code, these losses strain an already-inadequate supply. Earlier work in New Hampshire found about one licensed child care slot for every three children who lived within a 20-minute drive. Availability for the youngest Granite Staters is especially challenging: in 2024, while 99 percent of New Hampshire providers offered school-age care, just 56 percent served infants. These shortages are visible to New Hampshire families, who most commonly chose “no openings” (along with “not affordable”) as challenges they faced when seeking care.

Complex Systemic Challenges Drive ECE Offerings

The availability of child care slots is intricately connected to broader issues such as the state’s ability to recruit and retain early childhood educators, and the cost of care for families. Increasing equitable access to quality and affordable child care for New Hampshire families regardless of geographic location will require both short- and long-term efforts to address these systemic issues.

About the Authors

- Jess Carson is the director of the Center for Social Policy in Practice and a research assistant professor at UNH’s Carsey School of Public Policy.

- Harshita Sarup is a research scientist at the Center for Social Policy in Practice at UNH’s Carsey School of Public Policy.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by New Hampshire’s Preschool Development Grant, sponsored by the Administration for Children and Families (Award# 90TP0110). Additional project support was provided by the Couch Family Foundation.6

© 2024. University of New Hampshire. All rights reserved.