Key Findings

The Upper Valley of New Hampshire (Grafton and Sullivan Counties) and Vermont (Orange and Windsor Counties) is a cohesive region in many ways: for instance, workers flow across state borders and the demographic makeup of the area is similar across states. Yet the early childhood context of the Upper Valley has some sharp distinctions across state borders, many of which are tied to state policy decisions over time. This brief explores how state-level decisions manifest in the child care sector, contextualizing findings within the specific context of the Upper Valley as an interstate region.

Perhaps the most immediately visible difference between New Hampshire and Vermont’s early childhood landscape is the existence of public pre-kindergarten. New Hampshire remains one of only six states that does not have a state pre-kindergarten program, whereas Vermont enacted public pre-kindergarten effective July 2015. In 2021, the National Institute for Early Education Research ranked Vermont fifth in the nation for access to pre-kindergarten for four-year-olds—one of only seven states nationwide to enroll at least half of four-year-olds in state pre-kindergarten.1 Beyond just pre-kindergarten, however, New Hampshire and Vermont consistently make different choices within their early childhood serving systems from different staff-to-child ratios for certain age groups to different requirements for teacher qualifications.2

Upper Valley families have a median income of $82,900—statistically similar to the median income of families with children in Vermont statewide at $81,900—but lower than in New Hampshire at $100,800.3 While incomes are relatively high in the region, the median per-child cost for full-time child care in New Hampshire and Vermont ranges between $10,000 and $14,000 a year, depending on the child’s age.4 For Upper Valley families with two children, child care costs could consume one-third of family income or more.

Despite widespread high costs, families’ access to assistance is not uniform in the Upper Valley. The essential support for helping families afford child care is states’ child care financial assistance programs, also known as child care scholarships or subsidies. Although the primary funding source for child care assistance is the federal Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), the program is administered to states as a block grant, which allows states “flexibility within federal guidelines over key policy levers,”5 including determining income cutoffs for eligibility, co-payments required by families, and subsidy payment rates to providers. As such, implementation of child care scholarship programs looks very different within the Upper Valley, across state lines. The process for families is similar—apply for assistance, enroll child(ren) at any provider that accepts subsidies, and pay the required family contribution—although different eligibility guidelines and provider experiences likely create divergent family experiences across state lines.

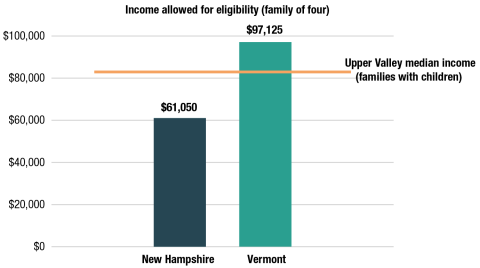

Vermont’s recently revamped scholarship program6 is significantly more generous than New Hampshire’s, which drives greater eligibility on the western side of the border. In short, a family of four is eligible for a scholarship in New Hampshire if their annual income is below $61,050. In Vermont, the same family could earn up to $97,128 and still qualify.7 Based on family income and family size qualifications,8 an estimated 52 percent of all Vermont households with young children are eligible for child care scholarships statewide.9 In New Hampshire, only an estimated 17 percent of households with young children meet the state’s income and family size eligibility requirements for child care subsidies. When New Hampshire’s income requirements are applied to Vermont households with young children, only 28 percent are eligible.

While income is not the only factor that determines eligibility—for instance, families must also demonstrate a need for care, like being employed—Figure 1 shows how the income cutoffs in each state compare with the median family income for Upper Valley families ($82,900). Based on those cutoffs, the half of Upper Valley families whose incomes fall below the median would all meet the initial income criteria for child care assistance in Vermont, although not all would in New Hampshire.

Note: Eligibility cutoffs current as of January 2023. Source: Carsey School of Public Policy analysis of 2020 American Community Survey, 5-year estimates; NH DHHS Family Assistance Manual; and VT Dept for Children & Families.

Because child care scholarships can bring high-quality care into reach for low-income families, state eligibility and implementation decisions are especially impactful for supporting equity in access. And because participation in the scholarship program is voluntary for providers, low-income families are further influenced by providers’ decisions to participate: families must rely on local providers accepting scholarships to access care in their communities.

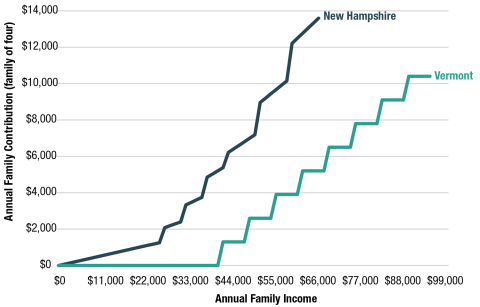

Beyond differences in eligibility for assistance, the expected contribution of New Hampshire and Vermont families receiving assistance varies substantially. In New Hampshire, “all families must contribute to the cost of care”10 when participating, through a mechanism called a “cost share.” In New Hampshire, cost shares increase at different increments of income-to-poverty ratios, so that the lowest-income participants pay 4.75 percent of their income to their child(ren)’s care, and the highest income participants pay 20 percent via cost share. In Vermont, the lowest income families pay $0, with the highest-income participants topping out at $200 weekly.11

The result of the states’ different approaches is that Vermont requires much smaller family contributions along the income spectrum than New Hampshire does. For instance, a two-parent, two-child family at 250 percent FPG ($69,374 per year) would be assigned an annual cost share of more than $10,000 in New Hampshire, and just $3,900 in Vermont. Figure 2 shows how the annual family contribution for a family of four shifts with income in each state.

Source: Carsey School calculations using NH DHHS Family Assistance Manual and VT Dept for Children & Families.

Box 2. Measuring Income Cutoffs for Eligibility

Poverty and income in the United States are measured in multiple ways. One such measure is the federal poverty guidelines (FPG), issued by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The FPG are a simplified version of the Census Bureau’s statistical measure of official poverty rates, and are mainly used for administrative purposes like determining whether a family is eligible for certain social safety net programs.12 The FPG are used to determine eligibility for child care financial assistance and to identify required family contribution levels. For 2022, the FPG for a family of four was $27,750, and did not vary by state.

In other settings, including several recent policy proposals, income eligibility is determined using statewide median income (SMI), the point at which half of all households in a state have incomes that are higher, and half have incomes that are lower (in 2021, SMI in New Hampshire was $88,465; $72,431 in Vermont). For policy purposes especially, it is common to set eligibility thresholds at some percentage of SMI. For instance, households under 80 percent of SMI in New Hampshire have incomes below $70,772 and below $57,945 in Vermont.13

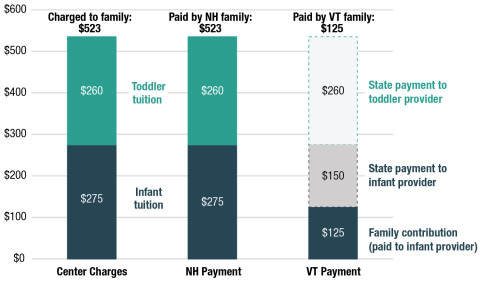

To better understand the implications of these gaps for real families, Figure 3 describes a hypothetical child care scenario for a family living in the Upper Valley. The family earns $75,000 per year and has a 6-month-old (infant) and a two-and-a-half-year-old (toddler). The family enrolls their children full time in a licensed child care center on the Vermont side of the Upper Valley. The provider has a three STep Ahead Recognition System (STARS) quality rating (the average across all Vermont providers) and charges tuition equal to the 75th percentile of three-STAR licensed centers statewide: $275 per week for the infant and $260 per week for the toddler. With the same income and receiving the same care for their children, whether the family lives in Vermont or New Hampshire will drastically alter what the couple owes for child care.

Note: Eligibility cutoffs current as of January 2023. Source: Carsey School of Public Policy analysis of 2020 American Community Survey, 5-year estimates; NH DHHS Family Assistance Manual; and VT Dept for Children & Families.

Because the family’s income is above the poverty level, they are ineligible for a child care assistance if they live in New Hampshire. They will pay the full $523 per week owed to their children’s child care providers. However, if the family lives in Vermont, they are easily income-eligible for assistance. At their income level, Vermont assigns the couple a weekly family share of $125—per family, not per child.14 The family contribution is paid to the youngest child’s provider first, then the state covers the remainder plus the entirety of the toddler’s tuition. As a result, the family’s final weekly bill is $125.

The implications of this cost savings for a moderate-income family are enormous over the course of a year. With nearly $400 in child care costs covered by the state each week, living in Vermont means that the family saves more than $20,000 per year in child care costs, which is more than one-quarter of their total income.15 It is easy to see how child care costs affect families’ employment-related decisions—is it worth it for a parent to stay at home instead?16

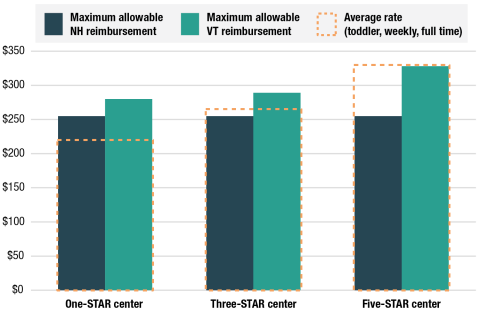

Beyond implications for families, inter-state policy differences also affect child care providers via the value of reimbursements that they receive when enrolling families utilizing scholarships. In all states, the value of a child care scholarship is determined not by the enrolling provider’s tuition, but rather, is capped at a state-selected maximum rate.17 While the federal government recommends that states set subsidies at the 75th percentile of child care costs according to their market rate survey, not all states do.18

Vermont’s recent program revisions bring reimbursements up to the 75th percentile, but New Hampshire reimburses at a lower rate, at the 60th percentile for children under age three and the 55th percentile for children over age three.19 In addition, Vermont varies its reimbursement rates according to the provider’s quality rating on the statewide STARS program. Providers at the “one-STAR” level receive the baseline (75th percentile) reimbursement, with incrementally higher reimbursements for higher-rated providers.20 New Hampshire has a different statewide quality recognition system, called Granite Steps for Quality, but reimbursement rates do not vary based on quality.21

xxx

Because higher quality providers tend to charge higher rates, this tiered reimbursement structure means that Vermont subsidies cover a fuller proportion of child care costs across the quality spectrum. Figure 4 shows the cost of enrolling a toddler full-time in a one-, three-, or five-STAR Vermont center (in orange). Because only residents can participate in a state’s scholarship program, scholarship assistance for enrollment in a Vermont center would be different for a family living in New Hampshire versus one living in Vermont. With either state’s scholarship, the family’s reimbursement could easily cover the average cost of a one-STAR center. But the maximum reimbursement rate of a New Hampshire scholarship would fall $10 short of covering tuition costs in a three-STAR center, and $75 short in a five-STAR center each week. As a result, the New Hampshire family could be required to pay that difference in the form of a co-pay each week. If the provider chose not to assess a co-pay, that discrepancy would be a consistent revenue loss.22

Although charging co-pays to families would help prevent revenue loss, providers aren’t always willing to do so. One Upper Valley child care provider, located on the New Hampshire side of the border said:

Note: Actual maximum reimbursements will be slightly lower in New Hampshire, as the family’s (income-dependent) required cost share is deducted from the allowable reimbursement before payment to the provider. Source: Carsey School calculations using NH DHHS Family Assistance Manual; VT Dept for Children & Families; & VT 2019 Market Rate Survey.

“That’s the other thing the state doesn’t explain to parents, is our tuition might be, say, $245 for a child…but the state’s maximum allotment might be $216. So the parents have to pay the difference… [the state is] not even up to the times, you know, [with] the way tuition is in the state. That would be helpful if they raise those rates [so] then we don’t have to charge parents…My families in this community…they can’t afford to pay that. They’re not doctors and nurses. They’re standard factory workers and retailers…They just can’t sustain that.”

At the same time, the provider recognized that leveraging a co-pay would mean, “I could easily give a staff member a dollar raise,” demonstrating how providers are put in the position to choose between the financial wellbeing of their staff and the families they serve.

Despite the significant support that subsidized child care can offer to individual families, the program is not a panacea in either state. According to the 2021 New Hampshire market rate survey, about half of surveyed providers received Child Care Development Fund scholarship reimbursements from the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) for care offered the prior day, while two-thirds received reimbursements at some point in the prior two years.23 In Vermont, it is not clear what number of providers participate in the Child Care Financial Assistance Program,24 but providers in either state may have reason to not accept families utilizing assistance.

First, accepting scholarships entails some degree of administrative burden for providers. One Vermont provider identified considerable differences across state lines, saying:

“When I was asked to do it [accept a subsidy from a New Hampshire family]…it was maddening. [I thought,] ‘I just can’t do this for one kid, because it’s just too much.’ Too time consuming. And Vermont had, and still has, what I consider, an easy system.”

Payment processes have varied by state over time too. One provider noted:

“It’s been a really long time since I’ve had a child on New Hampshire subsidy, but when they were…it was a lot harder, because it was recorded differently. They paid differently. Where Vermont was a set amount they sent you [even if] the kid was sick…New Hampshire was something like if the kid was sick and out then the parent had to pay. Which is a hardship on the family. I always felt bad saying, ‘I’m sorry your kid was sick this week. Now you owe me money.’”

Importantly, child care scholarships have historically had low reach among eligible populations. Although it is not yet clear to what extent the revised Vermont program is reaching eligible families, data from 2019 show that fewer than 5,000 unique children were served by the Child Care Financial Assistance Program25 and about 7,700 children were served by the NH Scholarship Program.26 These service counts amount to between 16 and 18 percent of each state’s population under 200 percent of the poverty line and under 13 years old.27 Although different factors influence eligibility and uptake, including families’ employment situations and the age of their children, this count suggests that the reach is incomplete (true also nationally, where scholarships reached just 16 percent of eligible children in 2019).28

Part of the reason for low scholarship use is likely to be challenges on the family enrollment side, rather than the provider acceptance side. In New Hampshire, there is some evidence that families may not be aware of the child care scholarship program, and if they are, may believe they are ineligible.29 Families may find the paperwork burdensome, or that even with a scholarship the combined cost share and co-payments still make care prohibitively expensive. These tensions highlight the ways care may not be accessible even for those with scholarships, particularly under new, multidimensional definitions of “access,” stating access to care means “that parents, with reasonable effort and affordability can enroll their child in an arrangement that supports the child’s development and meets the parents’ needs.”30

Data from the state of New Hampshire indicate that most of the applications for child care scholarships that are processed each month result in a denial. Between March 2020 and May 2022 (the most recent data available), 71 percent of applications processed were denied. While the data contain limited detail about reasons for denial, about one-third are due to incomplete paperwork, and around one-in-eight are due to the family exceeding income eligibility. More than 40 percent are denied for “other reasons” for which no additional detail are available.31

This brief focuses on child care scholarships, which indeed have potential to be a sustainable contributor to a robust early childhood sector. Existing research from the Urban Institute suggests that reliable funding is a main reason that providers accept scholarships, while low rates and administrative burden are the most common reasons they do not.32 Proposed legislation in both New Hampshire and Vermont would increase the reimbursement rates offered to providers, although with drastically different levels of impact. In New Hampshire, for instance, a new bill proposes to bring reimbursements to the 75th percentile of the market rate.33 In Vermont, proposed legislation would require the state to reimburse providers for the total cost of care, rather than a share of market rate costs.34 Both states propose payments based on enrollment, rather than attendance.

To support families, both states have legislation proposed that would expand eligibility for scholarship (to about $75,000 in New Hampshire and $125,000 in Vermont). Vermont proposes dropping the requirement that families be seeking employment to become eligible for scholarship and would remove required contributions for families below 185 percent of the poverty guideline.

Importantly, Vermont’s proposed legislation identifies specific and concrete mechanisms for centering equity in its scholarship program, as recommended by the Alliance for Early Success and others.35 This includes establishing an expert-guided approach to outreach and engagement of underserved communities and the establishment of state funds specifically reserved for funding scholarships to families whose immigration status might preclude them from participating in the existing scholarship program. Vermont’s multi-pronged approach to widen eligibility, enhance participation among underserved families, and maximize reimbursement for providers align with many of the policy strategies outlined by national child care experts. These kinds of system-level changes hold promise for better supporting both families in need of care and child care providers.

Data on child care scholarship eligibility are sourced from administrative documents from the Vermont Department for Children and Families, Agency of Human Services and the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, cited throughout. Calculations are created using eligibility thresholds in effect as of January 2023; new eligibility thresholds go into effect in Vermont on February 26, 2023. Child care scholarship eligibility estimates were derived from ACS 2020 1-year microdata via IPUMS (Steven Ruggles, Sarah Flood, Ronald Goeken, Megan Schouweiler, and Matthew Sobek. IPUMS USA: Version 12.0 ACS 1-year 2020. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2022. https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V12.0). Quotations are drawn from interviews with child care providers in the Upper Valley collected by the Carsey School in 2022 and 2023, under a protocol reviewed and approved by the University of New Hampshire’s Institutional Review Board (UNH IRB #FY2023-27).

This brief focuses on child care scholarships, but data availability limitations affect our ability to draw full conclusions about scholarships and access in the Upper Valley. Specifically, neither state could share provider-level data on scholarship acceptance and receipt upon request. Having provider-level data on scholarship acceptance could support screening for potential spatial mismatches between the location and type of providers that accept scholarships and concentrations of potentially eligible families. Further analyses could examine, for instance, how the location and characteristics of providers accepting scholarships might align with the distribution of families of color, in occupations with nontraditional work hours, or who are English language learners as part of an equity-focused analysis of access.

In addition, although scholarships are important, the program is not the only mechanism for investing in early childhood. Unfortunately, neither New Hampshire nor Vermont has a unified method for accounting for child-focused spending that would allow for comprehensive comparisons of non-scholarship funding streams across states. A 2020 Vermont Needs Assessment describes why such details may not be available at the state level: “Vermont does not have a universal early childhood budget that identifies the resources, finances, and supports allocated across all early childhood programs and services. There is a lack of resources (person time and political will) available to crosswalk all budget data sources to create such a budget and use it to inform decision-making.”36

- The National Institute for Early Education Research. “The State of Preschool 2021.” State Preschool Yearbook. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Graduate School of Education, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. https://nieer.org/state-preschool-yearbooks-yearbook2021.

- Vermont licensing regulations via “Licensing Regulations for Center Based Child Care and Preschool Programs.” Department for Children and Families, Agency of Human Services. https://outside.vermont.gov/dept/DCF/Shared%20Documents/CDD/Licensing/CC-CenterBased-Regs.pdf.

- Difference between Upper Valley and Vermont median family incomes is not statistically significant. Carsey School of Public Policy analysis of 2020 American Community Survey 5-year estimates.

- Calculated using the most recent market rate surveys for each state: Michael Kalinowski, Fanny Kalinowski, and Isabella Kalinowski. 2021. “2021 New Hampshire Child Care Market Rate Final Report.” DHHS Contract Activity 42117810. Concord, NH: Department of Health and Human Services, State of New Hampshire. https://www.dhhs.nh.gov/sites/g/files/ehbemt476/files/documents/2021-11/2021-mrs-final-report.pdf; and “Vermont 2019 Child Care Market Rate Survey and Cost of Care Report: Executive Summary.” 2019. Waterbury, VT: Child Development Division, Department for Children and Families, Agency of Human Services. https://outside.vermont.gov/dept/DCF/Shared%20Documents/CDD/Reports/CC-MRS/CC-MRS-Report-2019.pdf.

- “OCC Fact Sheet.” 2022. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Child Care. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ/fact-sheet.

- https://outside.vermont.gov/dept/DCF/Shared%20Documents/CDD/CCFAP/CCFAP-Rate-Structure-Presentation.pdf

- In New Hampshire, the program has “two-tiered” eligibility, meaning that to qualify for assistance, a family must earn below a certain amount; once eligible, the family can earn slightly more money before losing their child care support, to allow “time to transition toward financial independence.” See https://www.dhhs.nh.gov/fam_htm/html/935_gross_monthly_income_limits_fam.htm. The initial eligibility cutoff in New Hampshire is 220 percent of the federal poverty guidelines (FPG), which translates to $61,050 per year for a family of four. To remain eligible, family income must not exceed 250 percent of the FPG ($69,375). In Vermont, the child scholarship program is open to families with higher incomes—up to 350 percent of FPG, or $97,128 per year for a family of four. Vermont calculations in this brief utilize eligibility thresholds in effect from July 2022 into February 2023 and do not account for the revised guidelines in effect February 26, 2023. For Vermont income guidelines, see https://outside.vermont.gov/dept/DCF/Shared%20Documents/Benefits/CCFAP-Income-Guidelines.pdf. For federal poverty guidelines, see https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines/prior-hhs-poverty-guidelines-federal-register-references.

- Note that each state has additional eligibility requirements not considered here, such as the accepted service need requirement in Vermont (https://dcf.vermont.gov/benefits/ccfap), and similar work/school requirements in New Hampshire (https://www.nh-connections.org/families/child-care-scholarship/). Vermont income guidelines available at: https://outside.vermont.gov/dept/DCF/Shared%20Documents/Benefits/CCFAP-Income-Guidelines.pdf; New Hampshire income guidelines available at: https://www.nh-connections.org/uploads/2022/06/Form-2532-Child-Care-Scholarship-Income-Eligibility-Levels-2022.pdf

- Note that while state policy guidelines use family income and family size for eligibility thresholds, these thresholds were applied to household income and size measures in ACS 1-year 2020 microdata (using household experimental weights recommended for 2020 analyses and replicate weights).

- https://www.dhhs.nh.gov/fam_htm/html/938_cost_share_and_provider_co_pay_fam.htm

- https://outside.vermont.gov/dept/DCF/Shared%20Documents/Benefits/CCFAP-Income-Guidelines.pdf

- “Poverty Guidelines.” 2022. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines.

- Carsey School of Public Policy analysis of U.S. Census Bureau 2021 American Community Survey (one-year estimates).

- https://outside.vermont.gov/dept/DCF/Shared%20Documents/CDD/CCFAP/CCFAP-Rate-Structure-Presentation.pdf

- Of course, while child care scholarships are not the only factor that varies across state lines—for instance, housing costs, the presence of an income tax, and property taxes also vary across state lines—this exercise illustrates a potentially important factor in families’ decision-making around where to live.

- Schochet, Leila. 2019. “The Child Care Crisis Is Keeping Women Out of the Workforce.” Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/child-care-crisis-keeping-women-workforce/

- https://www.dhhs.nh.gov/fam_htm/html/937_reimbursement_rates_fam.htm; https://outside.vermont.gov/dept/DCF/Shared%20Documents/CDD/CCFAP/CCFAP-Capped-Rates-Effective-07.03.2022.pdf

- “CCDF Payment Rates—Understanding the 75th Percentile.” 2017. National Center for Child Care Subsidy Innovation and Accountability Brief. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Child Care. https://childcareta.acf.hhs.gov/resource/ccdf-payment-rates-understanding-75th-percentile.

- “State of New Hampshire: Inter-Department Communication.” December 4, 2019. https://dhhs.nh.gov/sr_htm/html/sr_19-23_dated_11_19.htm.

- https://outside.vermont.gov/dept/DCF/Shared%20Documents/CDD/CCFAP/CCFAP-Rate-Structure-Presentation.pdf

- https://www.nh-connections.org/families/quality-care-matters/

- Beyond reimbursement levels, definitional differences emerge across state lines, affecting reimbursements defined by child age and level of enrollment; Vermont’s definitions tend to be more generous. For instance, Vermont providers serving infants receive the higher infant reimbursement rates until a child is 24 months old; in New Hampshire, infants transition into the “toddler” category at 18 months. Whereas Vermont reimburses providers for full time versus part time care, New Hampshire carves part time into two groups, that include half time and a lower-reimbursed part time category. Vermont also adds an “extended time” reimbursement for children in care more than 50 hours per week. “Child Care Financial Assistance State’s Capped Rates: Effective July 3, 2022.” Waterbury, VT: Child Development Division, Department for Children and Families, Agency of Human Services and https://www.dhhs.nh.gov/fam_htm/html/937_reimbursement_rates_fam.htm.

- Kalinowski, Michael, Fanny Kalinowski, and Isabella Kalinowski. 2021. “2021 New Hampshire Child Care Market Rate Final Report.” DHHS Contract Activity 42117810. Concord, NH: Department of Health and Human Services, State of New Hampshire. https://www.dhhs.nh.gov/sites/g/files/ehbemt476/files/documents/2021-11/2021-mrs-final-report.pdf

- Information is limited on the number of sites that receive CCFAP reimbursement in Vermont. All licensed and registered sites are asked to complete a Provider Rate Agreement upon opening and every two years after that reports their market rates and “agrees to the expectations of receiving CCFAP,” however, it is not clear that all sites fill out the agreement, nor that all sites that “agree” actually receive CCFAP. The 2019 market rate survey describes the number of programs with a Provider Rate Agreement (PRA) by age group, but sites are not uniquely identified, making a tally of those with active PRAs impossible. See “Vermont 2019 Child Care Market Rate Survey and Cost of Care Report: Executive Summary.” 2019. Waterbury, VT: Child Development Division, Department for Children and Families, Agency of Human Services. https://outside.vermont.gov/dept/DCF/Shared%20Documents/CDD/Reports/CC-MRS-Summary-2019.pdf.

- Point in time count, as of October 1, 2019. Via https://vermontkidsdata.org/data/datasets/unduplicated-count/.

- Greenway Strategy Group. 2022. “Strategic Plan Analysis Findings.” April 12, 2022.

- Using 200 percent of poverty as an approximation of eligibility in New Hampshire and under the prior Vermont program rules. Count of low income children are weighted estimates derived from the 2019 American Community Survey microdata; population data verified using single-year of age data via the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2020 Population Estimates Program.

- Chien, Nina. 2022. “Factsheet: Estimates of Child Care Eligibility and Receipt for Fiscal Year 2019.” Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/child-care-eligibility-fy2019.

- Carsey School of Public Policy analysis of 2022 New Hampshire Preschool Development Grant Family Needs Assessment Survey.

- Definition first appears in Friese, Sarah, Van-Kim Lin, Nicole Forry, and Kathryn Tout. 2017. “Defining and Measuring Access to High Quality Early Care and Education: A Guidebook for Policymakers and Researchers.” OPRE Report 2017-08. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. See also Paschall, Katherine, Elizabeth E. Davis & Kathryn Tout. 2021. “Measuring and Comparing Multiple Dimensions of Early Care and Education Access.” OPRE Report 2021-08. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Data were obtained upon request to the Bureau of Family Assistance and cover the period of April 2020 to May 2022. Data were analyzed across this full period and also into six month-periods covering April 2020 through September 2020, October 2020 through March 2021, April 2021 through September 2021, and October 2021 through March 2022, with no meaningful differences in patterns over any period.

- Rohacek, Monica and Gina Adams. 2017. “Providers in the Child Care Subsidy System: Insights into Factors Shaping Participation, Financial Well-Being, and Quality.” Research Report. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/95221/providers-and-subsidies.pdf.

- See the introduced SB 237-FN: https://legiscan.com/NH/text/SB237/id/2660658/New_Hampshire-2023-SB237-Introduced.html

- See the introduced S.56: https://legislature.vermont.gov/Documents/2024/Docs/BILLS/S-0056/S-0056%20As%20Introduced.pdf

- Alliance for Early Success. 2020. “Build Stronger: A Child Care Policy Roadmap for Transforming Our Nation’s Child Care System.” https://earlysuccess.org/ChildCareRoadmap. Note that the Alliance is a network of early-childhood policy advocates at state and national levels. Two Let’s Grow Kids-affiliated advocates from Vermont are listed as “State Allies” in the “Build Stronger” report.

- Vermont’s Early Childhood Data & Policy Center. 2020. “Vermont’s Early Childhood Systems Needs Assessment 2020: Data Gaps.” https://vermontkidsdata.org/data/data-gaps/.

The authors are incredibly grateful to the early childhood educators in the Upper Valley who were willing to share their expertise and valuable time to help us better understand their needs. Additional thanks to state administrators in New Hampshire and Vermont who entertained our data requests, to Carsey School staff Kamala Nasirova and Ben Hammer for research support, and to Laurel Lloyd and Bailey Schott at the Carsey School for layout and communications support.

This work was made possible through generous funding and partnership from the Couch Family Foundation.

This brief is part of a series of work funded by the Couch Family Foundation aiming to explore the early childhood education and care landscape of the Upper Valley. See the Related Links for the other two briefs in this series.

Sarah Boege, MPP, is a senior policy analyst with the Center for Social Policy in Practice at the Carsey School of Public Policy. Sarah supports Carsey research through data collection and analysis, GIS mapping, and translating and disseminating research findings. At the core of their past and current work is the use of research to inform more equitable and accessible policy, practice, and decision-making.

Jess Carson, PhD, is the director of the Center for Social Policy in Practice and a research assistant professor at the University of New Hampshire’s Carsey School of Public Policy. Jess studies how policy affects people, focusing on how legislative and administrative decisions shape access to resources available through work, the social safety net, and community settings.