download the brief

Key Findings

Hidden in the shadows of New Hampshire’s opioid epidemic are the children who live with their parents’ addiction every day. They fall behind in school as the trouble at home starts to dominate their lives, they make the 911 calls, they are shuttled about to live with relatives or in foster care, and they face an uncertain future when their parents can no longer care for them.

In the United States, one in eight children under age 18, or about 8.7 million, live with at least one parent who has a substance use disorder.1 Although many of these children will not experience abuse or neglect, they are at increased risk for maltreatment and child welfare involvement compared with other children.2 Parents who seek treatment can recover, yet parents using opioids are often using other substances and confronting behavioral health issues that complicate recovery.

Having one or both parents using opioids can have negative consequences on child development. Such children show increased emotional or behavioral problems and difficulty with attachment and establishing trusting relationships. The family environment when a parent uses opioids is typically characterized by secrecy, loss, conflict, violence or abuse, emotional chaos, role reversal, and fear.3 Research shows that adverse childhood experiences such as a parent’s addiction and drug use increase the likelihood of the child using drugs by age 14 and of continuing use into adulthood.4 Stable connections and emotional bonding with a caregiver, be it a parent, grandparent, other relative, or child care provider, enable children to make social and emotional connections and build resilience that can buffer against the negative experience of living with a parent with a substance use disorder.

This brief examines parental substance use and who cares for children when their parents cannot. It uses data from the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services’ Division for Children, Youth, and Families (DCYF) Results Oriented Management and the Statewide Automated Child Welfare Information System (NH Bridges), and the American Community Survey (ACS).

DCYF Caseloads Increase

Concurrent with the rise of the opioid epidemic is a 21 percent increase in the number of child abuse and neglect reports accepted for assessment by DCYF, from 9,248 in 2013 to 11,197 in 2016 (Table 1).5 The proportion of assessments with a substance abuse risk factor (Box 1) increased from 41 percent in 2013 to 51 percent in 2016. Assessments with at least one allegation of substance use also increased after 2013. Rising caseloads are occurring throughout the state, with all district offices seeing an increase in the number of assessments since 2013 and a rise in the proportion of assessments at risk for substance use (Table 2).

Child Removal Associated With Substance-Related Allegations Doubled in Five Years

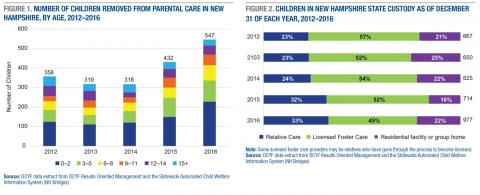

The number of children or youth removed annually from parental care increased by 53 percent between 2012 and 2016, from 358 to 547 (Figure 1). An increasingly larger proportion of children who were removed were under 3 years old, representing 42 percent of removals in 2016.

Substance-use-related issues are increasingly present in the lives of the children and youth who are removed from parental care. For example, 60 percent of children or youth removed from parental care in 2016 had a substance-related allegation in their assessment, double the percentage in 2012 (30 percent).6 Further, an increasing number of children or youth removed from parental care were born drug-exposed: 5 percent of children removed from parental care were born drug-exposed in 2016, up from 2 percent in 2012. The number of infants diagnosed with neonatal withdrawal, known as neonatal abstinence syndrome or NAS, in New Hampshire increased fivefold between 2005 and 2015, from 52 to 269.7 Working with hospitals, maternal health clinics, and pediatricians to encourage referrals to home visiting and services for families of newborns diagnosed with NAS, as well as encouraging parents to seek treatment, could be an important step to preventing child abuse and neglect and the removal of children from parental care.

Many children in state custody experience trauma and instability. Many are in need of mental health services, counseling, therapy, or child-parent psychotherapy. Children with stable connections and emotional bonding with a caregiver are able to make social and emotional connections and build resilience. Grandparents, relatives, foster parents, or quality child care providers can offer that emotional bonding to help children living in turbulent situations.

Voluntary and Preventive Services Limited By Lack of Funding

Most assessments do not end in a finding of child abuse or neglect: fewer than 6 percent of the 11,048 closed assessments resulted in a substantiated finding in 2016.8 Yet many showed substantial risk of parental substance use. Because of budget cuts in 2012 for community-based services, resources are more limited for voluntary or preventive services for families with a potential risk of child neglect.

Reinstating funding for voluntary and preventive services for unfounded cases in which there is nevertheless reasonable concern for potential child abuse or neglect will help families access the services they need and spot issues before they spiral into problems. The New Hampshire legislature recently passed a bill that would allow the Department to encourage families with unfounded but with reasonable concern for possible child abuse or neglect to seek voluntary services. The bill also appropriates funds for voluntary services and community-based prevention programs under the Child Protection Act.9

Seeking treatment can lead to recovery and can be essential to the well-being of children. One barrier to seeking treatment is cost;10 another is not having paid leave from work to cover the time needed to participate in outpatient or inpatient treatment programs. In New Hampshire, 37 percent of workers lack access to paid leave to tend to their own illness; this figure rises to 51 percent among families earning less than $60,000 per year.11 A bill considered, but not passed, by the New Hampshire legislature would create a paid family and medical leave insurance program.12

A third barrier to seeking treatment is lack of child care: parents may not be able to seek treatment if their child is not in a stable child care program. Current rules stipulate that recipients of child care scholarships maintain employment, and a New Hampshire bill recently passed will allow parents to maintain their scholarship while participating in a mental health or substance abuse treatment program.13

Who cares for the children?

Many grandparents (Box 2), aunts, uncles, siblings, other extended family, and close friends step forward to care for children when their parents cannot. With the rise in opioid use, more relatives are being called upon because parents have died, are incarcerated, are using drugs, are in treatment, or are otherwise unable to take care of children.14 The child welfare system relies on grandparents and relatives to foster children. National data show that 29 percent of all children in foster care are living with relatives,15 but, since many children being raised by relatives reside outside the formal foster care and DCYF system, the role of relatives in caring for children is likely much greater.16

DCYF data show that at the end of 2012, 667 children were in New Hampshire state custody and placed in out-of-home care. By 2016, this number had risen to 977, an increase of 46 percent (Figure 2). Almost half of the children in out-of-home care in 2016 were living with a licensed foster care provider,17 one-third were living with a relative, and one-fifth were living in a residential facility or group home. The percent of children living with a relative increased from 23 percent to 33 percent from 2012 to 2016.

Services Available to Caregivers

Understanding the needs of grandparents raising grandchildren is important to help stabilize children who have been affected by parental opioid use. In June 2017, New Hampshire established a Grandfamily Study Commission to review data on barriers facing grandparents who are raising children, identify the causes of the barriers, and develop corrective action for addressing issues facing grandfamilies.19

As Table 3 shows, 49 percent of grandparents raising grandchildren in New Hampshire are living at twice the poverty level or lower, which means they likely struggle to make ends meet. Some of these grandparents are likely eligible for government supports, yet anecdotal evidence suggests that grandparents lack knowledge about services available to them as care providers. Government supports and services available for eligible grandparents and relatives caring for children include housing or child care assistance, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly the food stamp program). Children may be eligible for child-only TANF when the grandparents are not. For those grandparents struggling to make ends meet, but not eligible for government assistance, the addition of children into the household can result in financial stress.

Relatives who choose to establish a licensed relative foster home are eligible to receive financial assistance and additional support services. Depending on the age of the child, foster caregivers are eligible to receive between $16.59 and $21.41 per day for food and necessities, and $1.11 per day for clothing.20 Other benefits for foster children include counseling or health care, and caregivers may be eligible to receive child-care-related services such as transportation, financial assistance, child care payment assistance, and respite care.21

Grandparents raising grandchildren are under a lot of stress as they take on their new caregiver role and simultaneously grieve the plight of their adult child. Support groups for grandparents raising grandchildren have begun forming throughout the state. These are often organized by community-based nonprofit organizations, such as family resource centers, responding to their clients’ needs. The groups offer caregivers a chance to connect with others in similar situations, provide access to information about the legal and education system, give referrals for mental health providers for the grandparents and their grandchildren, and offer information regarding services. Research shows that when grandparents receive services, children perform better, both socially and mentally, and experience increased stability and permanency.22 Increasing the availability of grandparent support groups throughout the state could improve children’s stability and access to services.

One potential barrier to grandparents seeking TANF, despite financial need, is the TANF rule stipulating that the Division of Child Support Services may petition child support from the parents to reimburse the TANF funds. Grandparents may not seek TANF to avoid a strain on their relationship with their adult child, especially if the grandparent is seeking custody or guardianship.

Another issue concerning grandparents and relatives caring for children is financial support for child care. Forty-five percent of grandparents are employed, and many are low-income and thus perhaps eligible for child care scholarships. Maintaining a strong emotional connection with a child care provider can provide stability for children who are experiencing family turmoil.23 Anecdotal evidence suggests that child care staff and administrators are in need of trauma-informed care training, as children in their care are increasingly exhibiting behavioral health issues.

Conclusion

The opioid epidemic in New Hampshire has strained not only the families coping with addiction but also the service providers who work with children and families. Founded and unfounded cases of child abuse and neglect increasingly involve substance-use-related allegations or a noted risk for substance use. Providing services to families where there is reasonable concern for potential child abuse or neglect can help families access the services they need and identify issues before they escalate into problems. The major barriers preventing parents from seeking substance use treatment—cost, the limited availability of family leave, and the limited availability of child care—need to be addressed and in some cases were by proposed legislation.

When parents cannot provide care, children need support systems in place and stable connections so they can develop the capacity for emotional bonding and build resilience. Prevention and intervention efforts targeting children and youth may be beneficial in reducing the impact of parental opioid use.

Data

The Division for Children, Youth, and Families uses the Results Oriented Management database and the Statewide Automated Child Welfare Information System (NH Bridges) for keeping records on children and families involved with child protection and juvenile justice services. All required child welfare information is recorded, and the system is used to augment case management, workload management, budgeting, and resource management. NH Bridges can identify the status, demographic characteristics, case plan goals, and location of every child in state custody. Results Oriented Management is a feature-rich online report application that uses NH Bridges data to populate reports for staff. Data presented in this brief were extracted from NH Bridges by Allison Parent, senior data manager at DCYF.

This brief also analyzes American Community Survey data from 2014 and 2015 collected by the U.S. Census Bureau and obtained from the IPUMS files compiled by the Minnesota Population Center. The ACS collects information about whether the respondent is currently responsible for most of the basic needs of any grandchild(ren) under the age of 18 living in the same household or apartment, and demographic and economic information. All analyses are weighted using person-level weights provided by the Census Bureau.

Box 1: What are child abuse and neglect assessments?

Child protective service workers (CPSW) in the Department of Children, Youth, and Families provide services to families who may have experienced child abuse or neglect. The primary goal of the CPSW assessment is to ensure the safety of the child or children. Thoughtful planning of a child abuse or neglect assessment is critical in order to assess any immediate danger to the child and to maximize the safety of the child, other family members, and the CPSW during the assessment.

An assessment worker is tasked with determining whether an allegation of maltreatment is substantiated or not (founded or unfounded). There are many factors considered in the process, including substance abuse risk factors and allegations of substance abuse. A family is determined to have a substance abuse risk factor if there is potential excessive substance use or potential relapse of any person in the family; however, there is not necessarily evidence of the substance use being the main reason for the assessment. The presence of substance abuse allegations means there are direct concerns for child abuse and/or neglect precipitated by substance use that need to be further assessed. Substance use means the ingestion of alcohol, misused prescription/over the counter medications, inhalants, and illicit drugs (cannabis, hallucinogens, opioids, stimulants, or sedative hypnotics).

Box 2: The Profile of Grandparents Raising Grandchildren in New Hampshire

The American Community Survey collects data on the number and characteristics of grandparents who are responsible for the basic needs of grandchildren under the age of 18 who are living with them. In 2016, an estimated 7,983 grandparents were raising grandchildren in New Hampshire,18 though not all were raising them due to parental substance use-related reasons.

In New Hampshire, the majority of grandparents raising grandchildren were female, married, and white, non-Hispanic (Table 3). Seventy-three percent were 45 to 64 years old, and one-fifth were 65 and older. Sixty percent resided in a rural area.

In terms of education, 72 percent of grandparents raising grandchildren had a high school degree or less, and just over half were not employed. While 11 percent of grandparents lived in poverty, another 38 percent lived just above poverty (between 100 percent and 199 percent of poverty), meaning they were economically vulnerable and perhaps eligible for government assistance programs.

Endnotes

1. R.N. Lipari and S.L. Van Horn, “Children Living With Parents Who Have a Substance Use Disorder,” CBHSQ Report (Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2017).

2. Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, “New Directions in Child Abuse and Neglect Research” (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2014).

3. Laura Lander, Janie Howsare, and Marilyn Byrne, “The Impact of Substance Use Disorders on Families and Children: From Theory to Practice,” Social Work in Public Health 28 (2013): 194–205.

4. Shanta R. Dube, Vincent J. Felitti, Maxia Dong, Daniel P. Chapman, Wayne H. Giles, and Robert F. Anda, “Childhood Abuse, Neglect, and Household Dysfunction and the Risk of Illicit Drug Use: The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study,” Pediatrics 111, no. 3 (2003): 564–72.

5. About 20,000 reports of potential child abuse and neglect were made to the DCYF in 2016. Each report is screened to determine whether it is accepted for an investigation to assess child abuse or neglect.

6. Substance-related allegations include parental substance or drug abuse, or poisoning/noxious substances. Poisoning and noxious substances may be intentional or not, and include both illegal substances and household items.

7. Kristin Smith, “As Opioid Use Climbs, Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome Rises in New Hampshire,” Regional Brief No. 51 (Durham, NH: Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire, 2017).

8. This number differs from the total number of accepted assessments in 2016 because DCYF has 60 days to consider and close an assessment; thus, some accepted assessments in 2016 were not closed in 2016.

9. Senate Bill 592, relative to child welfare.

10. E. Park-Lee, R.N. Lipari, S.L. Hedden, E.A.P. Copello, and L.A. Kroutil, “Receipt of Services for Substance Use and Mental Health Issues Among Adults: Results From the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health,” September 2016, https://samhsa.gov/data/.

11. Kristin Smith and Nicholas Adams, “Paid Family and Medical Leave in New Hampshire: Who Has It? Who Takes It?” National Brief No. 105 (Durham, NH: Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire, 2016).

12. House Bill 628, relative to a family and medical leave insurance program.

13. Senate Bill 570, relative to the work requirement for the child care scholarship program.

14. Generations United, “Raising the Children of the Opioid Epidemic: Solutions and Support for Grandfamilies,” 2016.

15. “AFCARS Report, Preliminary FY2014 Estimates,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children, Youth, and Families, Children’s Bureau, 2015.

16. According to U.S. Census Bureau data, 15,371 (+/-1,096) grandchildren under 18 live with a grandparent householder in New Hampshire; however, the data do not distinguish if a parent is present in the grandparent household; see American Community Survey 2016 One-Year Estimates, “Table B10001: Grandchildren Under 18 Living With a Grandparent Householder by Age of Grandchild.”

17. Some licensed foster care providers may be relatives who have gone through the process to become licensed.

18. American Community Survey One-Year Estimates, “Table B10050: Grandparents Living With Own Grandchildren Under 18 Years by Responsibility for Own Grandchildren by Length of Time Responsible for Own Grandchildren for the Population 30 Years and Over,” 2016.

19. Senate Bill 148 established a commission to study grandfamilies in New Hampshire in 2017.

20. Rates are higher for specialized, emergency, or crisis foster care.

21. DCYF website, https://www.dhhs.nh.gov/dcyf/relativecaregivers.htm.

22. A. Garcia, A. O’Reilly, M. Matoin, M. Kim, J. Long, and D. Rubin, “The Influence of Caregiver Depression on Children in Non-Relative Foster Care Versus Kinship Care Placements,” Maternal and Child Health Journal 19, no. 3 (2015): 459–67; W. Crum, “Foster Parent Parenting Characteristics That Lead to Increased Placement Stability or Disruption,” Child and Youth Services Review 32 (2010): 185–90.

23. Martha Farrell Erickson, L. Alan Sroufe, and Byron Egeland, “The Relationship Between Quality of Attachment and Behavior Problems in Preschool in a High-Risk Sample,” Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 50, no. 1/2 (1985): 147–66, doi:10.2307/3333831.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Michael Ettlinger, Curt Grimm, Michele Dillon, Beth Mattingly, Amy Sterndale, Laurel Lloyd, and Bianca Nicolosi at the Carsey School of Public Policy; Michele Merritt and Rebecca Woitkowski at New Futures; MaryLou Beaver at Kids First Consulting; Deborah Schachter at the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation; Allison Parent, Jake Leon, and Joseph Ribsam at the Division for Children, Youth, and Families; and Patrick Watson for substantive comments and editorial contributions. The author also thanks Allison Parent at DCYF for providing the data, and the numerous individuals who answered the author’s questions.

This Carsey brief was funded by New Futures Kids Count and the Carsey School of Public Policy. The New Futures Kids Count research was funded in part by the Annie E. Casey Foundation. We thank them for their support but acknowledge that the findings and conclusions presented in this report are those of the author(s) alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Foundation.