Key Findings

The COVID-19 pandemic led to abrupt and momentous changes in economic and social systems beginning in March 2020 with widespread lockdowns in the United States. As “the workforce behind the workforce,” the early childhood education and care1 field was uniquely affected, navigating new requirements, substantial health concerns, and intensified staffing challenges, all in the context of an already-struggling sector.2 The pandemic offered states access to new temporary funding streams and served as a policy testing ground for many in the early childhood education and care sector. As the Upper Valley region of New Hampshire (Grafton and Sullivan Counties) and Vermont (Orange and Windsor Counties) straddles two state policy climates, pandemic responses and investments within the region varied. Yet the remaining needs post pandemic are felt across state borders: the temporary funding was not a panacea. This brief explores the pandemic era decisions and investments each state made to support the early education and care sector and describes some of the challenges ahead for the field.

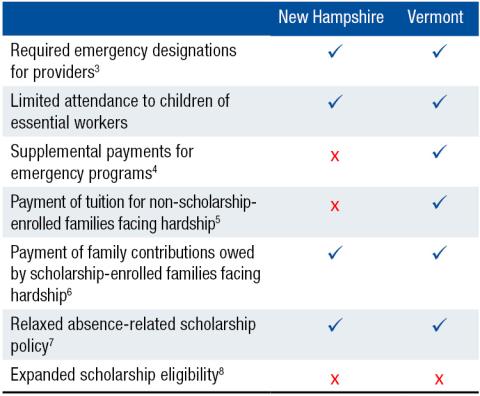

Early in the pandemic, states were tasked with designing responsive operational guidelines for child care. Responses varied by state, but often included mandated closures, emergency designation requirements for providers, rights to hazard pay for staff, and flexibility in payments for child care scholarship participants during closures or absences. Examples of New Hampshire’s and Vermont’s pandemic-era policy responses are described in Table 1.

Note: Enacted policies were often temporary and not temporally aligned across states.

COVID Relief for the Early Childhood Education and Care Sector

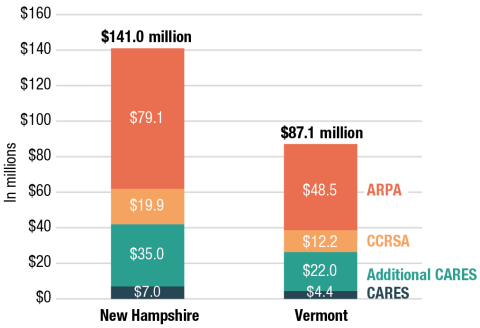

Federally funded relief for the child care sector has been appropriated in three key pieces of legislation since the start of the pandemic. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act), signed into law March 27, 2020, was the first to include child care-specific funding, with $3.5 billion in supplemental appropriations for the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG).9 Additional monies from CARES Act Coronavirus Relief Funds (CRF) awarded to states could be allocated toward child care-specific programs, which both New Hampshire and Vermont chose to do. Another $10 billion in support for the sector came via the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (CRRSA) in December 2020, followed by a final $39 billion via the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) in March 2021.10 Across the three packages, $141 million entered the sector in New Hampshire and $87 million in Vermont, as shown in Figure 1. Beyond child care-specific funding, child care providers could also apply for funds from more general programs, like those targeted to nonprofits or small businesses that each state enacted with its CARES Act funds.

Note: While this brief focuses only on child care providers serving at least some children under age five, relief funds in this figure were also available to providers serving only older children too, including through after school programs and summer camps. Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Child Care; New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services; Vermont Department for Children and Families; and the Bipartisan Policy Center.

To explore patterns in relief fund receipt, we requested provider-level records of pandemic relief funds from each state. Unsurprisingly, given the rapid deployment of these programs and intense administrative burden, neither state had records that linked the multiple funding mechanisms to specific recipients, nor had capacity to create such records upon request. Since only recipients of CARES Act funds were reported publicly in each state, we identified recipients of CARES and additional CARES funds for programs with available data11 from both states and parsed the child care providers out of the lists of all recipients in each state. Pandemic relief data here (Figures 2 and 3) thus only include a fraction of all child care relief dollars dedicated to the sector and describe the patterns of the earliest deployment of relief in the sector.

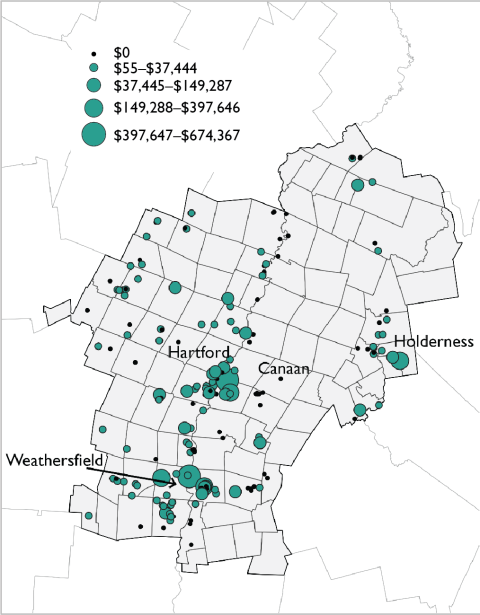

Upper Valley providers (open and serving at least some children under age five in 2021) received $5.2 million in the CARES Act funding programs examined here, representing a critical initial investment as providers faced both increased costs and lost revenue. Just over half (54 percent) of those dollars flowed into the New Hampshire side of the border, home to 42 percent of the region’s providers.

Among the 199 Upper Valley providers, more than half (53.8 percent) received at least some CARES Act funding. A greater share of providers on the Vermont side of the Upper Valley received funds (61.7 percent versus 42.8 percent on the New Hampshire side). However, on average, providers on the New Hampshire side of the border each received more funding, at $33,679 per provider, compared with $20,623 each on the Vermont side. This discrepancy may be driven by the fact that New Hampshire providers are more often center-based with greater numbers of slots.12

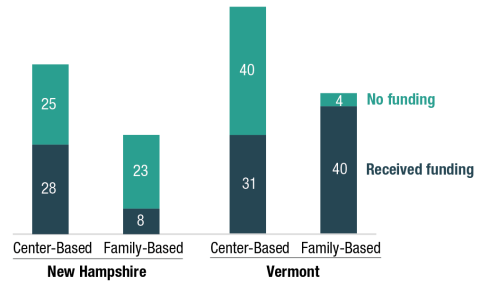

Figure 2 shows the prevalence of award receipt by provider type and state. In both states, between 45 and 55 percent of centers received CARES funding. However, the biggest discrepancy is in receipt among family-based providers: in Vermont, nearly all family-based providers still open in 2021 had received some funds, whereas only around one-quarter of New Hampshire family-based providers did.

Within the Upper Valley, award values were spatially uneven (Figure 3). In particular, the central cluster around Lebanon, Hanover, Hartford, and Hartland stands out for having many providers that received larger amounts of funding. Although neighboring this cluster, the towns of Canaan and Enfield, New Hampshire contain only providers that did not garner any funds. Holderness is also home to some of the more highly funded providers, along with the southern central cluster around Claremont and Weathersfield.

Note: Among providers serving at least some children under age 5 and open in 2021. Source: Carsey School of Public Policy analysis of state child care licensing data from summer 2017 and summer 2021 and of publicly available CARES Act relief award data from the states of Vermont and New Hampshire.

Note: Among providers serving at least some children under age 5 and open in 2021. Source: Carsey School of Public Policy analysis of licensing data from New Hampshire Child Care Licensing Unit and Vermont Child Development Division.

Were providers who received pandemic relief funds more likely to remain open into 2021? Although a prime opportunity for identifying potential policy impact, the available data limit our ability to draw conclusions.13

Award data show that at least some providers received pandemic relief funds but were no longer licensed and operating when data were next available in 2021. This was the case for six providers in the Upper Valley: one center on the New Hampshire side of the border and two centers plus three family-based providers on the Vermont side (one licensed, two registered). Closures among of this small group of providers do not appear attributable to receiving especially low-value relief awards: in fact, in each case, the awards that later-closing providers received exceeded average value for similar types of providers in their states.

More detailed data on the timing of provider closures and award receipt would have supported deeper analysis of the role of pandemic relief funding as a supportive mechanism for providers. However, the fact that at least some providers receiving funding closed demonstrates that funding, while essential for the sector, is sometimes not enough, and particularly if not received in the right form or timing, as discussed below.

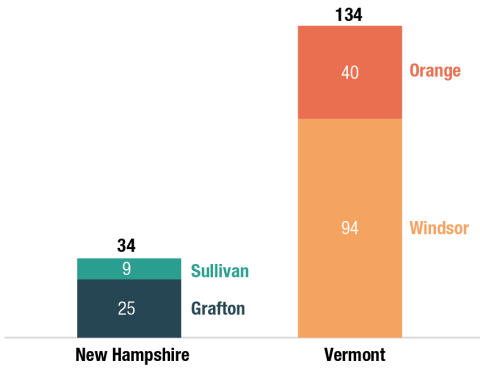

Both New Hampshire and Vermont have confirmed that the state has no plans to make public a list of ARPA award recipients as they did with CARES Act award recipients. However, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Child Care has released some aggregated, county-level data on ARPA Child Care Stabilization program grant recipients that shows receipt across the region.14 Since these data are only reported as total numbers of awards, the value of awards and characteristics of providers who received them are unknown. However, award counts give a sense of the reach of Child Care Stabilization grants in each state.15

By the end of June 2022, 168 Upper Valley providers (serving children of all ages, not just children under age five) had received a Child Care Stabilization program grant.16 On the Vermont side of the border, 134 providers had received an ARPA-funded grant, compared with just 34 on the New Hampshire side (see Figure 4). Without provider-level information, it is difficult to identify why so few New Hampshire providers had received ARPA funds. However, just 590 awards were documented in New Hampshire, compared with 960 in Vermont, which appears to be driven in part by the low numbers of family-based providers receiving funding in New Hampshire (just 55 awards, versus 415 in Vermont).17

Since awards values are not included in the data from Figure 4, it is not possible to identify the extent of ARPA-specific Upper Valley investments. It is clear that New Hampshire providers have received fewer grants, but reports from the Office of Child Care suggest New Hampshire and Vermont providers are using the awards similarly. In both states, child care centers most commonly use their payments for staffing and personnel costs, while home-based family providers most commonly use payments for rent and mortgage costs.18

Note: As these data are only available in aggregate, the characteristics of these providers are unknown. Unlike in the rest of this brief, which focuses only on providers serving at least some children under age 5, it is not possible to remove providers who serve only school-age children from this tally. Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Child Care.

One major difference between funds from ARPA and earlier programs is its increased flexibility. In a series of one-on-one interviews (see Data and Methods section), we asked Upper Valley early childhood educators to reflect on the pandemic-era relief awards their program had received. Several noted their appreciation for the enhanced flexibility that ARPA funding opportunities provided.

Earlier programs’ tight spending deadlines were especially difficult. In an illustrative conversation, a Vermont-based program director described appreciating the flexibility in allowable uses of CRRSA funds (staffing, utilities, supplies) but found its requirements to spend funding down monthly and record detail by spending category difficult. The structure placed providers under pressure and offered limited ability for strategic, planned usage of funds. The provider described, “That kind of felt like a curse. Like, I have to use it this month—what am I going to use it for?”

In contrast, ARPA Child Care Stabilization grants only require reporting at the end of the grant period and providers can carry remaining funds from month to month rather than having to spend a monthly allotment. The same Vermont-based director further explained, “It’s a little more flexible and you don’t feel that rush—like I have to spend this money right now and then afterwards it’s like…I don’t know if that was the best way to spend it.”

The providers we interviewed were in unwavering agreement that the area most significantly in need of investment was staff. Interviewees were also in consistent agreement that this investment needed to come in the form of increasing wages to recruit and retain early childhood educators. Providers struggled to leverage ARPA funds to meet these goals when the nature of the funding was temporary: any salary increase with ARPA funds would need to be alternately funded when the funding expires. A New Hampshire-based director noted:

“You can only charge the families so much and so then we can only pay our employees so much, without more funding that’s coming through. There [are] all these ideas out there, but people have to hurry because this ARPA funding isn’t going to last forever.”

With limited revenue streams, raising tuition has long represented the only opportunity for increasing wages, which providers see as an unsustainable solution. One provider explains:

“It’s ridiculous to me that people get paid like $14 an hour to shape little minds. It’s such an important job…[But] where are you going to take the costs from? Like, are you going to put the burden on the parents? Parents are trying to just make ends meet as it is…To not put all the burden on parents, there has to be a stipend or something through the state to help that. Or businesses need to do something differently, or the state needs to do something differently.”

Unsurprisingly, funds invested in the early childhood education and care sector helped keep providers afloat through the pandemic. Many interviewed providers credited relief funds with keeping their doors open and retaining staff. At the same time, most interviewees also emphasized just how precarious the future looks, unsure if their organization will still be open in another six months. While pandemic relief helped, the major enduring sector challenges—particularly staffing—have been exacerbated during the pandemic and continue to pose a serious ongoing threat to solvency. As one provider described, “Unless something happens soon, I think you’re going to see it start to crumble. It’s already been crumbling.”

In a February 2023 interview, one Vermont provider described the various relief funds as “all very successful,” but expected the impending end of relief funding would trigger more closures. Despite these successes, the provider continued, “Unfortunately, somewhere around mid-pandemic it came down to: it doesn’t matter how much money you throw at it—it’s not going to work anymore…I can’t even tell you the number of centers that have said ‘we can’t operate anymore, we absolutely cannot.’”

That pandemic relief funds have become a critical revenue stream for some providers clarifies the impact those funds have had. But with inflation-linked growth in material costs, rising facility costs, and increased staff wages from pandemic-era retention efforts, overall operating expenses have risen. Simultaneously, the effects of shifting demand may play a role, although they are not well documented.19 The Vermont provider from above relayed a conversation with a peer who felt reliant on pandemic relief funds to remain operational:

“And I said, ‘Well, what happened? You didn’t have [relief funds] before and you kept going.’ And she’s like, ‘Yes, but I don’t have the kids [enrolled at typical levels], so I don’t have the tuition dollars. I still have all the overhead and the different facilities costs have increased. Rent and insurance have increased, gasoline for field trips has increased. Everything is different.’”

Pandemic relief funds provided necessary, but limited, grants to providers. Now, bold policy actions to enhance and bolster the child care sector long-term are required to create a path toward a more sustainable system. One element is expanding the reach and value of child care scholarships. By engaging more families and offering higher-value reimbursements, child care scholarships can become a more reliable and feasible revenue stream for providers. Vermont’s recent expansions to eligibility plus advocates’ plan to expand even further would have significant impacts for Vermont families.20 Legislative proposals to link scholarship values to the cost of care could grow the provider impact of scholarships too, although unlikely to be a standalone solution to the sector’s challenges.

Absent federal policy movement, some states are choosing to invest in their own early childhood workforces, including Maine’s recent passage of legislation to make permanent the ARPA-initiated wage supplements for early childhood educators, drawing on its general fund to support the effort after ARPA funds are depleted.21 New Hampshire is proposing workforce recruitment and retention incentives in its 2023 session,22 and Vermont is proposing pay parity between early childhood educators and public school teachers.23

Beyond wages, policies that make healthcare benefits more widely available and affordable for early childhood educators may support staff retention. Vermont’s Let’s Grow Kids has identified making early childhood educators categorically eligible for no- or low-cost health insurance as a policy priority for 2023.24 This strategy was echoed in interviews of Upper Valley educators as a concrete area of improvement: “The state of Vermont could help us by having a group [health] insurance that we can all dip into, reasonably priced.”

Initiatives that support paid training and mentorship opportunities into the field show promise for building workforce pipelines, including new philanthropically supported efforts already unfolding in the Upper Valley.25 Other efforts are federally proposed, including the “Childcare Workforce and Facilities Act,” co-sponsored by New Hampshire Senator Jeanne Shaheen, which would provide competitive grants to states for the purpose of enhancing compensation, building facilities, and helping workers obtain “portable, stackable credentials” that increase mobility in the child care workforce and expand offerings in rural areas.26 As pandemic-era supports phase out, a mixed set of approaches to support staff and stabilize the sector are necessary: “This ARPA funding isn’t going to last forever.”

This brief uses child care licensing data from the New Hampshire Child Care Licensing Unit and the Vermont Child Development Division (summer 2017 and summer 2021). For each state, the 2017 records were merged and matched with 2021 records to identify provider closures and openings. Providers were matched based on a combination of information including physical addresses, mailing addresses, owner names, and provider names. Partial matches were reviewed on a case-by-case basis using any matched information as context. For example, a case where the owner’s name differs but the physical address and business name is the same would be designated as a match (e.g., ownership may have changed, but the provider did not close).

For consistency across states and given data structure constraints, Vermont’s age group definitions were used to classify age groups served by providers in both states. Vermont child care licensing regulations specify that:

- “Infant” means a child who is at least six (6) weeks and under thirteen (13) months of age. (Section 2.2.25)

- “Toddler” means a child between thirteen (13) through thirty-five (35) months of age. (Section 2.2.62)

- “Pre-kindergartener” means a child who is thirty-six (36) months of age up until school age. (Section 2.2.36)

- “School age” means a child who is five (5) years of age or older and currently attending kindergarten or has completed kindergarten or a higher grade. (Section 2.2.46)

This brief uses publicly available, state-reported COVID-19 relief award data related to the CARES Act. Data documenting individual award recipients were available via the New Hampshire Governor’s Office for Emergency Relief and Recovery (GOFERR) and via the Vermont Agency of Administration.

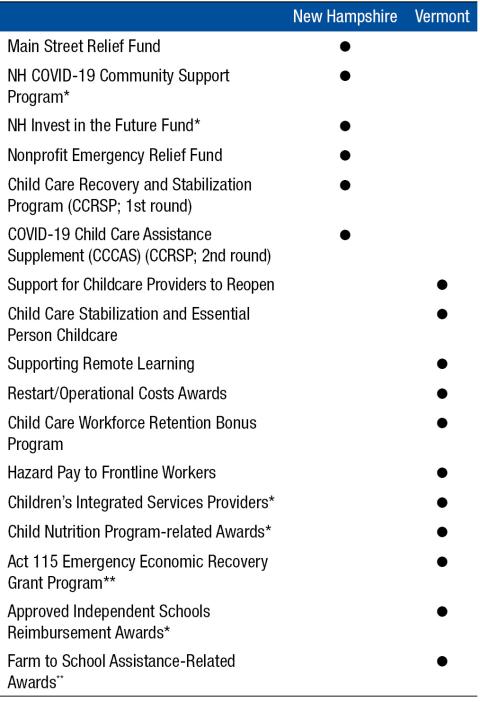

States were given flexibility in developing and distributing their COVID relief programs. Both New Hampshire and Vermont developed dozens of relief programs, each with their own eligibility requirements and rules. However, child care providers were not eligible for every award program, and Table 2 lists the programs for which recipient-level data were publicly available and through which we identified that at least one child care provider received an award. Each program listed is incorporated into the award dataset used in this brief. Although the research intent was to identify whether specific award mechanisms or award values were especially effective policy levers for keeping providers afloat, the intensive differences in relief programs across state borders, the lack of data on non-CARES Act funding packages, and the inability to retrieve historical licensing data across the region makes this impossible to answer.

For all programs listed in Table 2, we reviewed a list of all award recipients and manually matched using name and address details to child care providers in our child care licensing datasets. Award amounts were also included. When an umbrella organization or a multi-site organization received an award, distribution across subsidiary sites was not always specified. In these cases, the award amount was divided evenly among sites. This approach was chosen for consistency, although it’s unlikely that this is how funds were exactly distributed.

Quotations are drawn from interviews with child care providers in the Upper Valley collected by the Carsey School in 2022 and 2023, under a protocol reviewed and approved by the University of New Hampshire’s Institutional Review Board (UNH IRB #FY2023-27).

Notes: Both federal funds made available to states via supplemental appropriations for the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) and state Coronavirus Relief Funds (CRF) are included. Data from the CARES Act’s Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) were administered directly through the U.S. Small Business Administration and not available for consideration here. Also excluded is a second round of “Main Street Relief Fund” disbursals in New Hampshire, given that the recipient list for these funds was released much later than others. A single asterisk indicates programs for which a single child care provider in the Upper Valley was identified as having received an award, and two asterisks indicate that two Upper Valley providers received this type of award.

- Note that in this brief, we use the term “early childhood education and care” instead of the more widely used “early childhood care and education” per the Couch Family Foundation’s preference. This phrasing centers the educational nature of the sector’s work and underscores the educational expertise of its workforce.

- Jess Carson and Marybeth J. Mattingly. 2020. “COVID-19 Didn’t Create a Child Care Crisis, but Hastened and Inflamed It.” Carsey Perspective, August 24. Durham, NH: Carsey School of Public Policy. https://carsey.unh.edu/publication/child-care-crisis-COVID-19.

- https://governor.vermont.gov/press-release/governor-phil-scott-orders-implementation-child-care-system-personnel-essential-covid; https://www.dhhs.nh.gov/news-and-media/nh-dhhs-announces-more-250-providers-achieve-emergency-child-care-provider.

- https://bipartisanpolicy.org/download/?file=/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Vermont.pdf.

- Between March 18, 2020 and April 4, 2020, the state paid full tuition payments for private pay families and full co-pay amounts for families using scholarships directly to programs, as long as those programs continued to pay their staff at full salary. Beginning on April 5, 2020, the state paid 50 percent of family costs (tuition or co-pays), and if families declined to pay the remainder, providers could unenroll the family and receive full tuition reimbursement until the slot was reenrolled. See “Child Care Financial Support Programs During the COVID-19 Closure Period,” https://legislature.vermont.gov/Documents/2020/WorkGroups/Senate%20Health%20and%20Welfare/COVID-19/W~Melissa%20Riegel-Garrett~COVID-19%20Childcare%20Financial%20Supports~4-9-2020.pdf and https://bipartisanpolicy.org/download/?file=/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Vermont.pdf.

- National Women’s Law Center. 2021. “Changes in State Child Care Assistance Policies During the Pandemic.” https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/State-Child-Care-Assistance-Policies-During-Pandemic-NWLC-1.pdf. See also https://bipartisanpolicy.org/download/?file=/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/New-Hampshire.pdf.

- National Women’s Law Center, “Changes in State Child Care Assistance Policies During the Pandemic,” 2021.

- Ibid.

- https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ/policy-guidance/ccdf-discretionary-funds-appropriated-cares-act-public-law-116-136-passed-law.

- https://www.ffyf.org/timeline-of-covid-19-relief-for-the-child-care-industry-and-working-families/.

- Note that one prominent CARES Act program for which data are not included here is the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). At the time of data aggregation for this project, a list of PPP recipients was not made public through state channels. A later, supplementary source (via the U.S. Small Business Administration) was identified indicating that at least some child care providers participated in the program, but it was not possible to verify the extent to which these data were complete at the time.

- Carsey School of Public Policy analysis of data from New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services and Vermont Department for Children and Families.

- Although questions arise around the efficacy of certain relief fund mechanisms in preserving the region’s child care supply, historical licensing data was not available upon request for the region, which precludes our ability to examine providers’ relief fund receipt alongside their operating status. Data from 2017 exist, but given the instability of the sector, it is not possible to fairly attribute all closures between 2017 and 2021 to the pandemic.

- “ARP Child Care Stabilization Funding State Fact Sheets.” 2022. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Child Care. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ/map/arp-act-stabilization-funding-state-fact-sheets.

- The count of Upper Valley providers here does not match the totals identified in earlier sections of this paper as ARPA data are not disaggregated by provider type. Thus, totals may include at least some providers who only serve school aged children, and/or some providers who were not open in 2021.

- This compares with 107 Upper Valley providers recorded as receiving CARES Act funding.

- “ARP Child Care Stabilization Funding State Fact Sheet,” 2022. For the data used in Figure 4, exact award amounts are also unknown. It is also not possible to link them to CARES Act award recipients. Data presented here are as of June 30, 2022, although the Child Care Stabilization program will continue into 2023 in Vermont and at least through 2022 in New Hampshire.

- Ibid.

- Demand data are not well documented (for instance, there is no unduplicated count of all children on child care provider wait lists), but a co-mingling of changing parent work conditions, family financial strains, and emergent socioemotional needs among children may be reshaping demand in yet-unmeasured ways.

- See the introduced S.56: https://legislature.vermont.gov/Documents/2024/Docs/BILLS/S-0056/S-0056%20As%20Introduced.pdf.

- 130th Maine Legislature. May 5, 2021. Legislative Document No. 1652. https://legislature.maine.gov/legis/bills/getPDF.asp?paper=HP1223&item=1&snum=130.

- See the introduced HB-566: https://gencourt.state.nh.us/bill_status/legacy/bs2016/billText.aspx?id=306&txtFormat=html&sy=2023.

- See the introduced S.56: https://legislature.vermont.gov/Documents/2024/Docs/BILLS/S-0056/S-0056%20As%20Introduced.pdf.

- Let’s Grow Kids. 2023. “2023 Legislative Agenda.” https://letsgrowkids.org/client_media/files/2023LegislativeAgenda.pdf.

- A pilot program is underway in at least one Upper Valley center, aiming to build workforce pipelines that include delineated paths toward credentials and compensated mentoring relationships. Authors’ personal communication with funders and program staff.

- “Klobuchar, Sullivan Introduce Bipartisan Legislation to Address Shortage of Affordable Child Care.” News Release, February 8, 2023. https://www.klobuchar.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/2023/2/klobuchar-sullivan-introduce-bipartisan-legislation-to-address-shortage-of-affordable-child-care.

The authors are incredibly grateful to the early childhood educators in the Upper Valley who were willing to share their expertise and valuable time to help us better understand their needs. Additional thanks to state administrators in New Hampshire and Vermont who entertained our data requests, to Carsey School staff Antonio Serna and Ben Hammer for research support, and to Laurel Lloyd and Bailey Schott at the Carsey School for layout and communications support.

This work was made possible through generous funding and partnership from the Couch Family Foundation.

This brief is part of a series of work funded by the Couch Family Foundation aiming to explore the early childhood education and care landscape of the Upper Valley. See the Related Links for the other two briefs in this series.

Sarah Boege, MPP, is a senior policy analyst with the Center for Social Policy in Practice at the Carsey School of Public Policy. Sarah supports Carsey research through data collection and analysis, GIS mapping, and translating and disseminating research findings. At the core of their past and current work is the use of research to inform more equitable and accessible policy, practice, and decision-making.

Jess Carson, PhD, is the director of the Center for Social Policy in Practice and a research assistant professor at the University of New Hampshire’s Carsey School of Public Policy. Jess studies how policy affects people, focusing on how legislative and administrative decisions shape access to resources available through work, the social safety net, and community settings.

Kamala Nasirova is a PhD student in the department of education at the University of New Hampshire.