Key Findings

This Carsey Perspectives is a joint publication of the Carsey School of Public Policy and the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. This series presents new ways of looking at issues affecting our society and the world. The views expressed are the authors’ own and do not necessarily represent those of the Carsey School, the University of New Hampshire, or the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, the Federal Reserve System, or its Board of Governors.

Child care is foundational to the economy. Without it, many parents cannot work or reach their career potential. As child care programs rapidly closed in the COVID-19 pandemic, the degree to which work is enabled by child care became obvious,1 particularly for the 14 percent of workers parenting a child under age 6.2 Analyses of data collected in May and June 2020 found that 13 percent of working parents lost a job or reduced their hours due to a lack of child care.3

Today, the pandemic has made broadly evident what was already clear to America’s parents, employers, and care providers: the nation’s early childhood care system is fragile. Working parents face intersecting challenges as they seek high-quality, affordable care that is suitable for the ages of their children and available when and where they need it. One in four families paying for care spend more than 10 percent of their income on that care,4 well above the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ suggested affordability threshold of 7 percent.5 Half of Americans live in a child care desert,6 where access to formal quality care is essentially absent. And for parents living in a remote place, working nonstandard hours or having multiple young children, options are even more limited.

As pandemic-related strains to the child care system unfold atop this shaky foundation, we outline existing and new challenges, and we highlight possibilities for repairing the broken systems caring for our nation’s youngest children.

Despite the high cost to parents, licensed child care providers of all sizes struggle to generate a profit. For most child care programs, costs for space and materials are fixed, although they are relatively small in comparison to labor costs. Child care is a labor-intensive field, requiring many staff to care for children at mandated child-to-staff ratios, but the wages of individual workers are low. Most programs cannot afford to pay living wages, and benefits are scarce, despite the need for highly credentialed staff.7 Revenue increases typically would have to come from charging higher tuition, which would make many more families unable to afford quality care.

This dichotomy of high costs for families and low wages for workers derives from child care being a mostly private-pay system with limited public contributions. One outcome is high turnover as employees seek higher pay outside the industry, often in the public school system.8 Child care sits in stark contrast to publicly funded education, where teachers are paid significantly more than child care workers, have greater job security, and are typically offered benefits such as health insurance, paid sick leave, and retirement plans.9 Tensions between the push toward better-credentialed staff in the name of enhancing quality, inequities between pay for early childhood and public school educators, and high staff turnover have been bubbling toward a crisis for years.

These challenges pre-date the pandemic but have been exacerbated by the recent months of economic shutdown and health concerns. Many child care programs were forced to close at the onset of the pandemic, and others did so voluntarily out of concern for the health of their workers and the families they serve.10 As the economy reopens, four major concerns are at the fore both for parents and providers.

First, although some programs received assistance through CARES Act funding and forgivable Payroll Protection Program (PPP) loans, and though many laid-off workers were eligible for enhanced unemployment assistance, access has been uneven. The challenges of navigating funding may have been particularly acute for family child care, often operated by mothers in need of care for their own children and often without resources such as a well-connected board or employees with business acumen. For some, language barriers may have made accessing funds even more complex.

Second, for some programs staff shortages may be a pressing issue. Some child care workers ineligible for unemployment or seeking the security of a job may have found work elsewhere, though the extent of this is unknown and may be small given the scarcity of jobs and health concerns. Others may be unable to return to work if schools remain closed and their own children need care, or if they have concerns for their own health that preclude their return to a high-exposure environment like child care. On the other hand, the loosening of the labor market and changes in parent demand (discussed below) may counteract these shortages; the full extent of staffing concerns is still unknown and will take time to unfold.

Third, for center-based programs, facility costs like rent and insurance have continued to accrue, even without an inflow of tuition. And for those that have remained consistently open, dwindled enrollment may not have been enough to offset ongoing costs. Taken together, at least some child care programs were unable to stay viable and have shuttered their doors for good.

Finally, for programs that have remained afloat and have reopened or will soon, surviving the shutdowns is not the end of their financial pressures. As child care providers reopen, the ongoing health risks have led the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to recommend enhanced sanitization protocols and new restrictions on class sizes (see below), all of which are keeping operation costs high while reducing the number of families paying tuition.11 Even programs that survived the closures may not be able to continue operations.12

Child care providers have been navigating a maze of possibilities in the pandemic, including whether and how to reopen when allowed by state and local guidelines. The CDC provides ongoing guidance for child care centers that are open, including hygiene measures like handwashing and increased cleaning and instructions that staff and children stay home when sick.13 Other considerations include social distancing strategies such as reducing the number of children and staff in a group, eliminating mixing between groups when possible, and spacing children apart for naps and meals, along with screening and health checks for all staff and children.14

The implications of these new precautions are multiple. First, with guidelines around smaller group sizes and the need for more physical distance between children during indoor activities, existing facilities cannot accommodate their usual enrollment capacities.15 A June 2020 survey of child care providers from the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) found that 86 percent of respondents working in open programs said their program was serving fewer children than before the pandemic, with enrollment down an average of 67 percent.16 Second, despite fewer children present, requirements for more intensive cleaning and dividing children into separate spaces, each needing adequate supervision, means staffing needs are still high. Finally, providers must procure personal protective equipment, cleaning supplies,17 and materials to support distancing between children (e.g., non-shared art and sensory supplies) generally without new funds to offset these costs. Together, these new realities translate into higher costs of operation for child care programs, with fewer tuition dollars coming in to support those costs. Although there are some federal dollars flowing to child care now, these allocations are insufficient for many operators, and concerns exist about continued viability when loans through the PPP expire and CARES Act funding is exhausted by the end of the year. Policies like continuing payment of subsidies and parent co-payments to programs even when closed and pay increases for workers are also temporary and not enduring solutions.18

Nationally, it is unclear how long child care providers can sustain themselves without fuller external investments. In April, the Center for American Progress extrapolated from provider data collected by NAEYC in mid-March to estimate a loss of almost 4.5 million licensed slots—half of the already-inadequate nationwide supply.19 However, the NAEYC data underlying the estimates were collected before the CARES Act was passed,20 which along with the PPP loans included Child Care Development Block Grant funds to mobilize care for essential workers; funding for the Educational Stabilization Fund, which supports some state early education programs; and additional Head Start allocations.21 Although some providers reported that relief funds were difficult to access or inadequate,22 it is yet unknown how estimated losses of slots might have been stemmed or delayed by these funds. More recent data, however, suggest these funds were not a panacea, and the June child care provider survey from the NAEYC found that only 18 percent of respondents expected their program to survive longer than a year (note that this sample was not random nor representative but did include respondents from every state).23

At least one state has sought to quantify provider losses. The Wisconsin Policy Forum found that 39 percent of its state’s licensed providers had closed by May 19,24 although it is not clear that these closures were all permanent.25 In some hard-hit states like Arizona, child care programs reopened, experienced a cluster of COVID-19 cases, and closed again;26 some closed indefinitely.27 In short, it is unknown to what extent child care closures and losses will be sustained and to what extent supply will be irrevocably changed.28

Absent additional support for the child care sector, national supply of child care is likely to be dramatically reduced overall, posing a distinct challenge to economic recovery and creating hardship for the working parents of young children and for the more than 1 million child care workers (as of February 2020) who provide that care.29

As the nation moved unevenly into stay-at-home orders and then into various stages of phased re-openings, March and April’s job losses still have not been fully recovered,30 with unemployment rates rising from 3.5 percent in February to 11.1 percent in June.31 Jobs may eventually recover, but it could take years as many businesses permanently shutter and the underlying health situation persists.

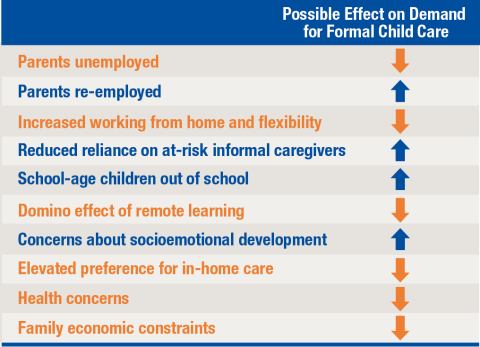

For those who remain employed or who find new work, it is not clear what demand for child care will look like moving forward. However, the contributing factors are varied and vast:

- High unemployment means fewer parents are working, and until they return to work they are unlikely to demand pre-pandemic levels of care. However, the reverse is also true: until child care is available to parents, they will face serious challenges in returning to pre-pandemic levels of work.

- With more workplaces transitioning to work-from-home models, whether permanently or not, parents may be able to arrange schedules to stay at home with children during what used to be usual daytime work hours, or to stagger their hours with a co-parent and reduce demand for care. Additionally, working from home may alter the geography of child care needs, increasing demand for care in residential areas rather than areas closer to the workplace.

- Families who usually relied on informal care from older relatives (e.g., grandparents) may find themselves seeking more formal care than usual to avoid compromising their relatives’ health.

- Families with school-age children may need substantially more care than is typically available for this age group, given the uneven spread of remote learning, hybrid learning with rotating in-person attendance, and possible closures among schools that do re-open. This demand will vary substantially at finely grained geographies, sometimes district-by-district, making it difficult to quantify for now.

- School delivery models may have implications for younger children, too. If older children are not in school, families who have younger children may opt out of child care altogether, planning to stay home, thereby pushing demand down.

- Families concerned about children’s socioemotional well-being may be especially eager to return to structured routines and be back to pre-pandemic demand levels.

- Until an effective vaccine is widely administered, parents may be uncomfortable with the health risks of sending children to child care. The NAEYC reports that 72 percent of respondents to their child care survey regularly heard from their families that they aren’t comfortable sending their children back to care.

- Among those needing to use child care, demand may shift to smaller in-home care or nanny/babysitter options, given greater potential viral exposure in center-based care.

- Finally, the pandemic has wrought changes in individual families that are hard to quantify yet: new constraints around work hours, transportation availability, disposable income, health status, and informal supports may all shape child care needs in ways that are both new and still fluid. For example, early evidence indicates women’s employment has declined more than men’s.32 It is unclear the extent to which this is driven by children’s care needs or industry/occupation, but in any case it is likely many women may opt out of employment until their young children enter school, given new barriers to child care.

Table 1 summarizes the effect of these factors on the demand for formal child care. The overall demand is unclear now, and that ambiguity is likely to continue as the health crisis and the economic recession persist. Lower demand may keep child care more accessible in the short term, even with decreased supply. But if parents are to eventually resume pre-pandemic labor force activity, it is unlikely that all, particularly lower-earning workers, will be able to generate alternative arrangements that do not involve additional formal child care. At that point, demand will increase and supply will be insufficient.

Note: Arrows indicate whether each factor is likely to increase (up) or decrease (down) demand for formal child care.

Absent policy intervention and sizable investments, access to formal child care slots is likely to become elusive for all but the highest-income families during traditional working hours. These families will still have options, including accessing care through a now-higher-priced center, or through in-home or nanny care. Faced with a shrinking supply, it is possible that more affluent families will increasingly leverage work-related flexibilities or access care in different ways, like through neighborhood co-ops, and perhaps desire less formal care than before the pandemic.

Workers without this flexibility, however, will still need child care at usual levels; as less-flexible jobs tend to be lower paid, it is the workers who need care the most who will be least able to afford it. This scenario has major equity implications for lower-income parents’ ability to remain employed. Without systemic change, we are likely to see widening disparities in child care access across income and race-ethnicity, as well as disparities in parents’ ability to work across income, race/ethnicity, and gender lines. Those who need lower-cost options, flexibility, and nonstandard care—including the front-line workers spotlighted by the pandemic, like health, retail, and delivery workers—will be precluded from access. Further inequities will be evident between parents’ and childless adults’ abilities to reach their labor market potential. Each calcifying disparity has dramatic implications for how and to what extent we can rebuild the economy.

As higher operational costs and lower density requirements continue, programs will deplete any remaining savings and pass costs on to families, absent outside assistance. Communities hardest hit by job losses and populated with families who were already struggling pre-pandemic and least able to pay for child care tuition are the communities most likely to see their local child care programs fold.33 Together, these higher prices and restricted slots mean that access to formal child care could increasingly become the domain of families with the most resources.

Further, the shrinking numbers of child care providers don’t just affect families seeking care, but also the workers who supply that care. Child care as an industry lost 370,000 jobs between February and April 2020, less than half of which had been recovered as of June 1.34 The industry is almost exclusively populated by women, 40 percent of whom are women of color.35 Further, within the industry, women of color (particularly Black women) are more likely to work in assistant teacher roles and with the youngest children,36 meaning that they are likely to have been paid the least to begin with and be among the least able to buffer these job losses with savings and other resources. Even before the pandemic, these workers were in a precarious economic situation and, absent policy solutions, that precarity is likely to continue, and be accompanied by the increased health risks they face interacting with children and families during the pandemic.

A sizable investment is required to stabilize and support the child care industry, as evidenced by countries that have made this a priority.37 On July 29, 2020, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Child Care Is Essential Act, which would allocate $50 billion toward personnel, sanitation, training, and other costs of operating child care programs in the pandemic.38 A companion bill in the Senate would fold child care relief into broader education legislation.39 The House also passed a second bill, the Child Care for Economic Recovery Act, which includes $10 billion for grants aimed at constructing or improving child care facilities. This total of $60 billion in direct funding to the child care industry would be supplemented with additional funding to provide care to children of essential workers and to provide tax relief.40 These allocations meet or exceed recommendations by various industry experts, including the NAEYC, which called for $50 billion in March,41 and Senators Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Tina Smith (D-MN), who called for the same amount in April.42 A May 2020 op-ed from researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston did not include a specific price tag, but it urged policymakers “to be bold”43 in thinking about how to stabilize the child care industry and to consider an increase in funding that could significantly change the child care system rather than just return it to its pre-pandemic status. Finally, presumed Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden recently unveiled a $775 billion plan for supporting caregiving industries (both children and elders); it includes tax credits and subsidies for lower-income families paying for child care, tax incentives for businesses to build onsite child care, universal pre-kindergarten, and pay increases for early childhood educators.44

Identifying precisely how to best rebuild is a work in progress. Because of the enduring challenges facing child care, efforts to restructure the industry and broaden access to quality care pre-date the pandemic. Most pre-pandemic plans targeted cost-related challenges, including a possible expansion of the child and dependent care tax credit (enhancing the value and making it refundable), to widen access for lower-income households.45 Other approaches have included setting affordability thresholds for families and providing free care to the lowest earners.46 The Trump administration has also expressed interest in addressing the issue, providing a statement on its principles for child care reform in December 2019.47 Aside from the questions around funding and the high price tag of the plans, questions raised at the time around disadvantages for families who prefer non-licensed care (e.g., relying on a relative or a stay-at-home parent)48 take on increased salience in the pandemic context.

The current push to support existing child care programs with infrastructure improvements and more training and better wages for providers is a positive step in addressing some of the most pressing challenges described above. However, child care slots are not evenly distributed, and increasing access for families in places facing shortages of quality slots pre-pandemic—including in rural places, low-income neighborhoods, and in some communities of color49—is not an easy task. Many of the challenges driving pre-pandemic slot shortages are likely to remain relevant barriers post-pandemic; for instance, in rural America, staffing existing and new child care centers may be a challenge in an aging workforce50 that is at higher risk of COVID-19-related mortality.51 In any attempt to rebuild and improve the child care industry, efforts to target inequity in access will need to be made explicit to avoid reinforcing old disparities. One area in particular need of attention is the availability of quality care outside of standard work hours. Low-wage service-sector workers, disproportionately women and people of color,52 must navigate the compounding challenges of low-wage work and the need to secure child care during off hours. Importantly, any efforts to fully engage families with child care and work will have to account for the new realities of pandemic life. These include families’ newly developed preferences and constraints, the looming possibility of openings and re-closings due to viral spread, and, importantly, the need to deal with children and families who may have faced serious hardship and trauma in the preceding months.53

Whether families are struggling with the losses of a difficult economy or the benefits of increased workplace flexibility,54 having the support of a quality, safe, affordable child care slot is key to rebuilding the economy.

- https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/mar/30/if-coronavirus-forces-childcare-services-to-close-for-good-parents-will-be-left-stranded.

- Refers to the share of workers who are biological, adoptive, or step-parents to a child under age 6 who lives in the house. Authors’ analysis of U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey data, 2018 five-year estimates via IPUMS. Steven Ruggles, Sarah Flood, Ronald Goeken, Josiah Grover, Erin Meyer, Jose Pacas and Matthew Sobek, IPUMS USA: Version 10.0 [dataset], Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2020. https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V10.0.

- https://econofact.org/the-importance-of-childcare-in-reopening-the-economy.

- https://carsey.unh.edu/publication/child-care-costs-exceed-10-percent-family-income-one-four-families.

- https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2015/12/24/2015-31883/child-care-and-development-fund-ccdf-program.

- According to the Center for American Progress, 51 percent of Americans lived in a census tract where there is no licensed child care provider or there are more than three children under age 5 for every available licensed child care slot; see https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/early-childhood/reports/2018/12/06/461643/americas-child-care-deserts-2018/.

- https://www.epi.org/publication/child-care-workers-arent-paid-enough-to-make-ends-meet/.

- https://www.childresearch.net/projects/ecec/2012_04.html.

- https://hechingerreport.org/high-turnover-and-low-pay-for-employees-may-undermine-states-child-care-system/.

- https://cscce.berkeley.edu/files/2003/turnoverchildcare.pdf.

- http://www.hunt-institute.org/covid-19-resources/state-child-care-actions-covid-19/.

- States may vary in how they adopt these guidelines in the regulations, but health concerns may also motivate centers to be even more cautious than is mandated.

- https://cscce.berkeley.edu/california-child-care-in-crisis-covid-19/.

- https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/schools-childcare/guidance-for-childcare.html.

- https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2020/04/27/will-child-care-be-there-when-states-reopen.

- https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/our-work/public-policy-advocacy/holding_on_until_help_comes.survey_analysis_july_2020.pdf.

- https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/our-work/public-policy-advocacy/holding_on_until_help_comes.survey_analysis_july_2020.pdf.

- https://tryingtogether.org/hazard-pay-child-care/.

- https://www.ncdhhs.gov/news/press-releases/ncdhhs-provide-financial-support-essential-workers-and-child-care-providers.

- https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/early-childhood/news/2020/04/24/483817/coronavirus-pandemic-lead-permanent-loss-nearly-4-5-million-child-care-slots/.

- https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/our-work/public-policy-advocacy/effects_of_coronavirus_on_child_care.final.pdf.

- https://www.ffyf.org/covid-19-recovery-working-together-as-an-early-learning-care-community/.

- https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/our-work/public-policy-advocacy/child_care_and_the_paycheck_protection_program.pdf; https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/our-work/public-policy-advocacy/holding_on_until_help_comes.survey_analysis_july_2020.pdf; https://www.alaskapublic.org/2020/06/18/childcare-providers-say-theyre-falling-through-the-cracks-without-pandemic-recovery-aid/.

- https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/our-work/public-policy-advocacy/holding_on_until_help_comes.survey_analysis_july_2020.pdf.

- https://wispolicyforum.org/research/wisconsins-child-care-sector-needs-care-itself/.

- https://www.wpr.org/report-many-child-care-providers-closed-due-covid-19-how-many-can-reopen-unclear.

- https://kvoa.com/news/top-stories/2020/06/19/caregiver-at-davis-monthan-child-care-center-tests-positive-for-covid-19/.

- https://news.nhcgov.com/news-releases/2020/06/highest-daily-case-count-of-covid-19-cluster-identified-in-child-care-facility-in-new-hanover-county/; for more on child care programs that have opened and had to (re)close see https://www.miamiherald.com/news/coronavirus/article243670537.html.

- A survey from the Bipartisan Policy Center indicated that 60 percent of providers had closed when the data were collected March 31–April 4 (https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/nationwide-survey-child-care-in-the-time-of-coronavirus/). However, the survey methodology indicates that these data were collected among parents, not providers, and the data are better described as more than 60 percent of parents reported that their provider had closed. The latter interpretation appears here (https://bipartisanpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/BPC-Child-Care-Survey_CT-D3.pdf).

- https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CES6562440001.

- https://carsey.unh.edu/COVID-19-Economic-Impact-By-State.

- https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/laus.pdf; https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/laus_03272020.pdf.

- Clifford, Robert and Marybeth J. Mattingly. In Preparation. “Unemployment Insurance Claims during COVID-19: Disparate Impacts across Industry and Demography in New England States.”

- https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/early-childhood/reports/2020/06/22/486433/coronavirus-will-make-child-care-deserts-worse-exacerbate-inequality/.

- https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CES6562440001.

- https://cscce.berkeley.edu/files/2018/06/Early-Childhood-Workforce-Index-2018.pdf.

- https://cscce.berkeley.edu/files/2018/06/Early-Childhood-Workforce-Index-2018.pdf.

- Publicly funded child care is expensive, even in more typical times. While countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development average 0.7% of gross domestic product on care, France and the Nordic countries spend much more and the United States less, at about 0.5%. This suggests the United States would need to dramatically increase its commitment, likely to more than triple the current amount, to keep up with leaders like Sweden. See: https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF3_1_Public_spending_on_childcare_and_early_education.pdf.

- https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/29/house-passes-bailout-for-child-care-industry.html.

- https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/4112/actions.

- https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/29/house-passes-bailout-for-child-care-industry.html.

- https://www.naeyc.org/resources/blog/child-care-needs-emergency-support.

- https://medium.com/@SenWarren/our-plan-for-a-50-billion-child-care-bailout-6d94dde53c77.

- https://www.bostonfed.org/news-and-events/news/2020/06/childcare-oped-may-2020.aspx.

- https://www.latimes.com/politics/story/2020-07-21/biden-caregiving-child-care-education-economy; https://www.npr.org/2020/07/21/893446328/new-biden-plan-would-spend-nearly-800-billion-on-caregiving.

- https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1967; https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/931; https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/749; https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1696.

- https://www.economy.com/mark-zandi/documents/2019-02-18-Child-Care-Act.pdf; https://www.warren.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Universal_Child_Care_Policy_Brief_2019.pdf.

- https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/white-house-principles-child-care-reform-increasing-access-affordable-high-quality-child-care-america/.

- https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/02/elizabeth-warrens-misguided-call-for-federal-childcare/583615/; https://www.nationalreview.com/magazine/2019/03/11/leaning-out/.

- https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/early-childhood/reports/2020/06/22/486433/coronavirus-will-make-child-care-deserts-worse-exacerbate-inequality/.

- https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1372; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5738994/.

- https://carsey.unh.edu/publication/older-rural-pop-increases-estimated-COVID-death-rates.

- https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/community-development-issue-briefs/2020/the-effects-of-the-novel-coronavirus-pandemic-on-service-workers-in-new-england.aspx.

- https://nyulangone.org/news/trauma-children-during-covid-19-pandemic.

- https://medium.com/rapid-ec-project/between-a-rock-and-a-hard-place-245857e79d9d.

The authors thank their colleagues Michael Ettlinger and Sarah Boege at the Carsey School of Public Policy, and Sarah Savage and Prabal Chakrabarti at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston for comments on an earlier draft. Additional thanks to Patrick Watson for editorial assistance, Laurel Lloyd for layout and production, and Nick Gosling for digital media support.

Jess Carson is a research assistant professor with the Vulnerable Families Research Program at the Carsey School of Public Policy.

Beth Mattingly is a policy fellow at the Carsey School of Public Policy and assistant vice president in the Regional and Community Outreach Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.