download the brief

Key Findings

As outlined in the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, there is an urgent need for mechanisms that effectively scale proven interventions for tackling some of humanity’s toughest challenges (United Nations 2015). While there are exemplary models that have proven to be highly effective, there are relatively few examples that have achieved large-scale replication.

The application of business format franchising, one of the most popular and successful commercial business models over the last several decades, has recently emerged as a potentially effective and efficient approach to addressing societal challenges at scale. Social sector franchising harnesses business format franchising to reach large numbers of customers with necessary social goods and services. Social sector franchises are emerging around the globe, and are represented in diverse fields such as health care, clean water and sanitation, clean energy, and education.

This case study provides an overview of one such social sector franchise, Jibu. Jibu seeks to simultaneously provide lasting access to affordable drinking water and to contribute to economic development through a network of locally-owned franchise businesses in East Africa and beyond. This case study provides an overview of Jibu’s business model, operations, and approaches (Box 1).

As of December of 2017, Jibu has launched 200 businesses (more than one per week) across Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya, and Zimbabwe since January 2015. Jibu franchisees have produced more than 45 million liters of safe drinking water during this time, serving consumers who on average earn less than $5/day (www. jibuco.com).

Context

East Africa

East Africa is a diverse area, home to a complex patchwork of languages, cultures, and landscapes. On the United Nations’ Human Development Index, Kenya ranks 146th, Rwanda ranks 159th, and Uganda ranks 163rd out of 188 countries (United Nations Development Programme 2016). Two of the biggest issues in these populous, developing, equatorial countries are the lack of viable employment opportunities and water scarcity.

Jibu staff in front a Jibu retail shop in Kampala, Uganda.

Drinking Water and Poverty

Climate change, inconsistent political conditions, patchy regulation, industrial contamination, and a crumbling infrastructure all contribute to water scarcity in East Africa. Currently, 5 million people in Rwanda can’t access safe drinking water, and 900 children under 5 die per year from unsafe water consumption and poor toilets (WaterAid). Some must walk many miles each way to collect water in jerrycans, then boil it for safety before use. It takes time to gather, it takes time to boil, and it takes time for it to cool down enough to drink. UNICEF estimates that, globally, women and children dedicate a combined 200 million hours per day to collecting water (Wallace 2016). This creates additional barriers to employment and money-making activities for women, as they are required to surrender so much time to procuring drinking water for their families.

Additionally, the cost of charcoal is prohibitive for many impoverished families. In Rwanda, a sack of charcoal can cost half a week’s pay (9,500 RWF), at the median net hourly wage of 450 RWF (Besamusca and Tijdens 2013). Many people lack reliable income and social protection, with 39.6 percent making less than $1.90 USD per day in Rwanda, 66.4 percent in Kenya, and 65.4 percent in Uganda (The World Bank 2016). With the informal sector contributing to 90 percent of Sub-Saharan employment (African Development Bank Group 2013), there are few opportunities for social mobility and formalized entrepreneurial ventures. Lack of access to capital, complicated tax and fiscal processes, and slow-moving and opaque bureaucracies prevent many urban poor from improving their economic situations.

The Emergence of an Idea

After college, Galen Welch joined the Peace Corps as a health educator, and found himself questioning the long-term financial viability of many of the systems designed to serve the world’s underprivileged people. He wanted to create a financially sustainable model that could address society’s concerns, without sole dependence on philanthropy and public investment. His father, retired entrepreneur Randy Welch, advised charity-based water initiatives in Africa. This father-son team decided to combine their knowledge and ideas, and Jibu was formed.

Over $360 million USD of philanthropy and aid has been allocated in failed water initiatives in Africa, according to the International Institute for Environment and Development (Okereke 2017). Power imbalances, ineffective “feel good” missions, and prescriptive applications of charity were among the key failures the two saw in the philanthropy model of international aid. Galen believed that local “ownership” of a market-based solution would transcend humanitarian trends and funding priorities.

An Innovative Theory of Change

A lack of access to entrepreneurial and employment opportunities keep many in developing countries living in substandard conditions, with no feasible escape. Simultaneously, millions of people across the globe do not have access to clean drinking water. Jibu aims to transform these global predicaments into opportunities by providing underserved citizens with the resources to make meaningful change in their communities.

Through the franchise business model, Jibu aims to bring innovative solutions to accessing the basic human necessity of affordable, safe drinking water. First-time social entrepreneurs are equipped with Jibu’s water purification and other equipment, branding, training, and the capital required to launch franchise locations selling drinking water at prices lower than the charcoal it would cost to boil it. The goal is to create a profitable business for local entrepreneurs, creating numerous jobs in each community it serves, while promoting social well-being, mobility, and agency for new business owners.

Jibu franchise locations sell drinking water in reusable containers. Customers pay an initial deposit for the reusable water bottle, then pay only for the water when exchanging an empty container for a full bottle. While the affordability and time-saving aspects are important, the aesthetic appeal of the packaging and branding gives the impression of a “luxury” commercial bottled water, and does not have the negative social connotation of a traditional jerrycan.

Jibu’s patented, ergonomically designed bottle discourages use by mimics and protects the brand.

Business Model and Franchise Approach

Jibu formed a strategic partnership with Healing Waters International to develop the SolarPure UltraFiltration (UF) water purification system. As municipal water in East Africa can be unsafe and unreliable, this system uses UF plus three other filters to remove harmful impurities, bacteria, and parasites, while retaining healthy minerals and flavor. This system is powered by a solar-powered Grundfos renewable pump that propels thirty liters of water per minute and uses “less energy than a standard toaster” (Jibu).

Jibu’s bottles are custom designed and patented, with production in Nairobi, Kenya. Their bottles come in a variety of sizes, and the designs are ergonomic, with specific tapping features that cannot be used on other bottling lines. This feature is designed to prevent others from mimicking their offering or refilling with non-Jibu water, ensuring that the bottles will not be stolen and protecting their brand’s reputation.

It is important to note that Jibu intentionally targets a specific segment of the market in each region. In the interest of maintaining financial sustainability, Jibu does not give water away, necessarily excluding the true bottom of the pyramid (about 20 percent of the population). The top 10 percent of the population can readily afford commercially produced bottled water, so they are not the customers that satisfy Jibu’s mission. By reaching the remaining 70 percent of the population—customers who previously boiled water, but have the means to buy water if available at an affordable price—Jibu believes they can accelerate their impact while still focusing on financial viability, and scale a successful and profitable business model.

Jibu has focused on urban and periurban areas because of their high population density and municipal water sourcing. While the SolarPure UF system can purify water from any source, consistency in supply is important for their business model.

The Franchise/Microfranchise Model

Social sector franchising, like commercial franchising, is a business and marketing methodology that creates a network of replicated, locally-owned stores under the same model, branding, and mission. Jibu has created a system of independently owned and operated branded shops in East Africa that sell affordable drinking water.

Jibu as Master Franchisor

Currently acting as the Area Master Franchisor for all geographic markets, Jibu Corporate is responsible for selecting and vetting each franchisee. Upon selection of franchisee and location, Jibu executes the build-out, which includes custom-fitting and testing the water purification system, and painting and branding the store location. Jibu is currently responsible for facilitating and supporting quality control checks, and managing adherence to regulatory standards. It is responsible for training the franchisee in all aspects of running the business.

As expansion continues, the goal is to have a formalized Area Master Franchise framework, where an individual or organization acts as regional developer. This role will take the Jibu business model and develop in each regional area, assuming the responsibilities that Jibu Corporate currently has for each market.

The Franchisee Role

Franchise locations are selected based on their access to the consumer market, and Jibu typically only selects franchise locations with access to populations of 30,000 or more to ensure a sufficiently large potential customer base for each location. The franchisee is responsible for all aspects of the store’s day-to-day operations, marketing, hiring and managing personnel, and oversight of financial reporting. Each store location averages five members of staff: one store manager, one or two front desk attendants, a production manager, and one or two technicians.

The Microfranchisee Role

The microfranchise resellers operate in a “hub and spoke” model, expanding the reach of the franchisees outside of the strictly urban areas. The microfranchisees operate as licensed resellers of purified Jibu water. They coordinate pick-up of inventory at a franchise location, and therefore enable Jibu products to reach a wider breadth of customer base through formal and informal distribution points. This role also serves as a valuable means for training and vetting potential franchisees.

United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.

Proving the Model: Jibu Impact

Just as business format franchising has proven to be an effective business model for replication in the commercial world, social sector franchising offers a tantalizing solution to address some of society’s grand challenges at scale. However, the translation of franchising methods from commercial to social sector is still in its infancy, and not yet fully proven.

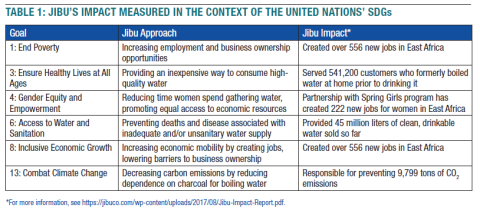

At the same time, Jibu’s success is suggesting promising results in terms of social impact and is making tangible progress against many of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations 2015) (Table 1).

One example is the “Spring Girls” program that Jibu developed with the help of Spring Accelerator, which works to spur entrepreneurship among adolescent girls aged 10–19. A Spring Girl graduate named Beliz started a microfranchise immediately after the program, then moved up to manage a Jibu store—and with her earnings, training, and sales and management experience, she has the potential to run her own business soon. As a staffer explained about the Jibu Spring Girl entrepreneurial model, “We let the girls do their business and now they can pay back Jibu and start having their own money and making their own rent, seeing progress and saving money now. Overall it’s an improvement in their lives from Jibu.”

Looking Ahead for a Bold Future

Jibu aims to create 1,000 new franchises and 3,000 microfranchises by 2022. In 2017 alone, it is introducing new franchisees in Uganda, Rwanda, and Kenya, with plans to expand to new markets in at least seven additional countries.

Jibu’s mission is to galvanize social entrepreneurs in underserved communities to ease the provision of affordable basic needs. Clean drinking water is its primary offering; however, it is envisioning methods of using the Jibu brand to distribute other necessities. For example, Jibu has partnered with The Ihangane Project, a nonprofit health care organization developing a pilot program selling affordable Aheza (fortified porridge) at ten microfranchise locations in Rwanda (The Ihangane Project 2015).

Jibu is a brand built on the premise of helping people address the challenges in their own community. They intend to keep looking for ways to meet community needs and to leverage the brand to make greater impact.

Methodology

This case study was developed over the period of nine months in Fall 2016–Spring 2017. It includes data from working sessions with company leaders, regular mentor-mentee phone calls, as well field research conducted in January 2017 with site visits to Jibu’s corporate office, nine different franchise locations, and fifteen different microfranchise locations. During the field research, in-depth interviews were conducted with franchise owners, store managers, microfranchise owners, and Jibu staff and customers. Field data were supplemented with company-provided documents and secondary data.

Box 1: About This Case Study

This case was examined as part of the Social Sector Franchise Initiative, a project of the Center for Social Innovation and Enterprise (CSIE).

The CSIE is a joint venture of the Peter T. Paul College of Business and Economics and the Carsey School of Public Policy, both at the University of New Hampshire (UNH). The CSIE also collaborates closely on this initiative with International Franchise Association (IFA), as well as the Peter T. Paul College of Business & Economics’ Rosenberg International Franchise Center, which is a respected authority on business format franchising.

The IFA NextGen competition is an annual business franchise contest that awards successful applicants with a week-long visit to the IFA’s annual convention in the United States. Through association with the IFA NextGen program, growing Social Sector Franchises are selected to participate in UNH’s Social Sector Franchise Accelerator (SSFA). The nine-month SSFA is a key part of the Social Sector Franchise Initiative (SSFI), where nascent social sector franchises are selected from a pool of applicants. Accelerator participants are provided with coordinated intensive mentorship by commercial franchise experts from the IFA, online learning, and an ecosystem of support. The process includes an active learning and research component conducted and documented by UNH faculty and students, culminating in this case study report.

The SSFI aims to help contribute to the growing field of social sector franchising by providing applied research and information on social sector franchising mechanisms to help inform success for practicing social sector franchise leaders, non-governmental organizations, investors, donors, and government officials.

References

African Development Bank Group. Recognizing Africa’s Informal Sector. March 27, 2013. afdb.org/en/blogs/afdb-championing-inclusive-growth-across-a... (accessed 2017).

Besamusca, Janna, and Kea Tijdens. “Wages in Rwanda.” WageIndicator. March 2013. http://www.wageindicator.org/main/documents/publicationslist/publication... (accessed 2017).

Jibu. How We Do It. http://jibuco.com/what-jibu-franchisee-looks-like-2/ (accessed 2017).

Okereke, O. Chima. “Causes of failure and abandonment of projects and project deliverables in Africa.” PM World Library. January 2017. http://pmworldlibrary.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/pmwj54-Jan2017-Oker... (accessed 2017).

The Ihangane Project. The Ihangane Project. 2015. http://www.theihanganeproject.com/ (accessed 2017).

The World Bank. Poverty & Equity Data Portal: Rwanda. 2016. http://povertydata.worldbank.org/poverty/country/RWA (accessed 2017).

United Nations Development Programme. Human

Development Data (1990-2015). 2016. http://hdr.undp.org/en/data (accessed 2017).

United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. 2015. http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed 2017).

Wallace, Rita Ann. UNICEF: Collecting water is often a colossal waste of time for women and girls. August 29, 2016. https://www.unicef.org/media/media_92690.html (accessed 2017).

WaterAid. Rwanda. http://www.wateraid.org/where-we-work/page/rwanda (accessed 2017).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the funders that have made this work possible, including our lead funder the Peter T. Paul Innovation Fund at the Peter T. Paul College of Business & Economics at the University of New Hampshire. We also acknowledge support from the International Franchise Association’s Social Sector Task Force, which provided volunteer mentor Peter Holt of The Joint Chiropractic who both served as an integral contributor to the Social Sector Franchise Accelerator and guided Jibu throughout the course of this case study. We also thank Jibu principal Galen Welsch and Jibu Uganda Country Director Mark Mutaahi for providing extensive access to the company information upon which this case study was based.