download the brief

Key Findings

After two decades of demographic and economic change, Coös County, NH remains poised between the impacts of manufacturing loss and the potential for growth in tourism. Physical and technological infrastructure investments are still necessary to meet the needs of the current population and to attract visitors, new residents, and new industries.

The natural beauty and unique character of the area are valued by residents and visitors alike. There is a challenge in maintaining a balance between the development of tourist amenities and other industrial growth that offers potential economic revitalization on the one hand, and environmental and cultural stewardship on the other.

Coös community leaders from a broad range of sectors are well positioned to collectively move the region forward, but there is some resistance to change. This resistance presents a barrier to innovation and adaptation to new socioeconomic circumstances. Listening to the voices of young people, newcomers to the area, and those who have left for a while and returned with fresh perspectives may yield long-term benefits.

The communities of Coös County are generally close-knit with a strong sense of local identity. A regional approach to planning can leverage local community strengths as well as the pooled assets and resources of the whole county.

Introduction

From 2008 through 2018, the Neil and Louise Tillotson Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation partnered with the Carsey School of Public Policy (formerly the Carsey Institute) at the University of New Hampshire for a research project titled Tracking Change in the North Country. Long-term research partnerships between foundations and university research centers are rare. This endeavor, lasting over a decade, reflected the fund’s commitment to data-driven grantmaking strategies targeting New Hampshire’s rural north and surrounding areas,1 particularly Coös County.

Tracking Change in the North Country established and bolstered multiple research components at the Carsey School by providing:

- Support for the Community and Environment in Rural America (CERA) survey and research. The CERA survey was conducted at multiple points in time with representative samples of adults in rural areas nationwide, including three times in Coös and surrounding counties (2007, 2010, and 2017), to gauge public perceptions of important economic, social, and environmental issues.

- Primary sponsorship of the Coös Youth Study, a ten-year panel study that followed the same youth ages 13 and 17 through early adulthood (2008 to 2018), focusing on their experiences of growing up in a transitional rural economy. The study explored, for example, youth health and social behavior, school and community attachment, aspirations and expectations for the future, and decisions regarding where participants will live, study, and work as young adults.

- Funding for in-depth qualitative studies of the region’s transformation, visions for the region’s future, and the work underway to restore and sustain the region’s economic viability (2009 to 2011).

- Financial backing to maintain the Northern New England Indicators website, which offers interactive data to the public on over thirty socioeconomic indicators on topics including population, income, employment, housing, and health.

In this brief, we summarize several major products of this research partnership and consider how they may inform future directions for North Country policy and programming.

The North Country/Coös County Region

Located in northernmost New Hampshire, bordering Canada, Coös County enjoys an abundance of scenic and productive forest land. Pulp and paper mills served as the economic backbone of the region for generations, but in the years before the Tracking Change study began, most of the mills had closed, resulting in widespread job losses.2 The Great Recession (2007–2009) reached into this distant corner of northern New England and compounded the effects of the mill closures. Local families and communities struggled to adapt to the changing economic circumstances.

Many in New England and beyond know Coös County for its natural beauty—spectacular mountains, forests, and rivers—and recreational amenities just beyond the heavy tourism of the White Mountains. Others may know Coös County, and particularly its population center, Berlin, only by its problems: declines in manufacturing, population loss, rising poverty rates, and challenges with education funding and school closures. These problems are serious and real and affect many North Country families. Nevertheless, we found that the communities of Coös County have remained strong, and that there are early signs of economic recovery emerging from the period of post-manufacturing decline. Earlier Carsey research in the region described a robust civic culture and social connectedness that have in recent decades protected Coös County communities from the socioeconomic blights often associated with rural American manufacturing decline. More recent research shows that these community assets endure despite ongoing challenges. There is still much work to do, and there are still many people committed to doing it. There is still cautious optimism that this work will yield future dividends in the form of healthy and vibrant North Country communities where children can grow up in safe and nurturing environments and thrive as productive adults well-prepared to give back to their hometowns.

Considerations for Charting a Path to a Thriving North Country

After two decades of demographic and economic change, Coös County remains an “amenity/decline” region poised between manufacturing loss and potential for growth in the tourism industry.

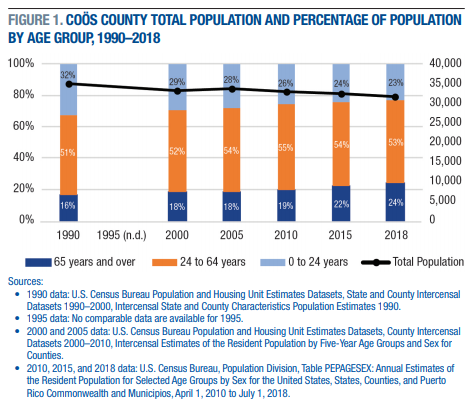

In their 2008 taxonomy of America’s rural areas (Box 1), Carsey researchers assessed demographic and economic indicators from 1990 forward and classified Coös County as an “amenity/decline” region. We looked at the same indicators for this report, tracking them through the most recently available data. The long-term trend shows continued population loss and an aging population (Figure 1), both associated with the decline aspect of amenity/decline.

Between 2001 and 2016, the total number of jobs in Coös County fell by nearly 10 percent, and manufacturing jobs fell by two-thirds. (Half of the remaining manufacturing jobs were lost after the publication of the original CERA report in 2008.) Three non-governmental employment sectors—retail trade, health care and social assistance, and accommodation and food services—have come to dominate the local economy.3 The top five employers in 2017 were two hospitals (Androscoggin Valley and Weeks Memorial), two tourist businesses (the Mount Washington Hotel and the Bretton Woods ski area), and the Federal Correctional Institution in Berlin.4

The economic and demographic transformations the county has experienced have made amenity-based growth an appealing path to pursue. In the most recent CERA survey, conducted in 2017, 81 percent of respondents identified tourism and recreation as a very important form of economic development, ahead of light manufacturing and new business (73 percent) and forest-based industries (67 percent). Indicative of the amenity aspect of amenity/decline, accommodation and food service jobs have increased by nearly 7 percent since 2001,5 and since 2010 meals and room taxes collected in Coös County have increased by nearly 19 percent adjusted for inflation6 (Figure 2). According to a city official, second-home ownership in Berlin has reportedly begun to increase—and along with it, property tax revenue—in part due to the area’s accommodation of all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) in state parks and downtowns.7 These are all indications of a growing amenities-based tourism economy.

A downside to transitioning to an amenity-based economy is that the service sector tends not to offer the stable, well-paying, lifetime jobs once offered by the manufacturing sector. The 2017 CERA survey found that lack of job opportunities was identified as the most important problem in Coös County, cited by 86 percent of survey participants. In the Coös Youth Study, many participants who moved away from the region after high school cited a lack of job opportunities, including a limited range of employing industries, as the primary reason for their departure.8 In addition to the quantity of available jobs, community leaders have expressed concerns about job quality in the rising service economy, as well as the readiness of the regional workforce for service-oriented employment.9 And while ATV tourism may have economic benefits, the noise and environmental impact has stoked public controversy over how to balance economic development while preserving natural amenities.10

The rise of tourism in Coös County has been incremental compared with the amenity-rich boom cycle characteristics of rapid population growth and development—although neither of these may be desirable to the portion of Coös residents who more strongly value the natural environment, elbow room, perceived safety, and familiarity of rural living anyway, despite concerns about population loss and economic challenges. Yet Coös residents seem to be more optimistic about the future: in the 2017 CERA survey 79 percent of participants predicted their communities will be about the same or better places to live in ten years, up 5 percentage points from 2007, and 70 percent hoped that young people moving away for opportunities elsewhere will return to work and raise families in Coös, up a remarkable 17 percentage points from 2010. Many participants in the Coös Youth Study who wanted to stay in Coös described it as a good place to raise children, and they cited natural amenities and sense of community as benefits of living in the region.11 In general, there is a sense that a portion of residents of all ages are willing to weather this period of manufacturing decline because of the high quality of life in Coös and the hope of future revitalization.

In 2008, CERA researchers made a series of recommendations for amenity/decline regions to develop their transitional economies and stem population loss. These included improved high-speed telecommunications to attract businesses and entrepreneurs; federal and state investments in infrastructure, community college, and business partnerships for on-the-job training of young workers; and support for health care, substance abuse programs, and early childhood health and education. The last ten years have seen some progress in these three areas:

- The Tillotson Fund’s Early Childhood Development (ECD) initiative has made great strides in establishing an integrated early childhood system in Coös County. This work, spearheaded by the Coös Family Support Project in 2007, has flourished into a multisector, countywide effort to increase regional capacity to serve families and young children. The collaborative comprises professionals in health care, infant and child mental health, child development, and early childhood education, with the shared goals of improving the accessibility and quality of services and improving outcomes for young children.12

- The State Economic and Infrastructure Development Investment Program, launched in 2008 by the Northern Border Regional Commission (NBRC), provides federal grant funding to projects designed to strengthen infrastructure and spur economic growth in New Hampshire, Maine, Vermont, and upstate New York. Recent Coös County projects supported by the program include installation of an efficient biomass heater at Weeks Medical Center; expansion of the Taproot Farm and Environmental Educational Center, which supports local agriculture and environmental education; and additional clinic space for expanded behavioral health and substance abuse treatment at Coös County Family Services.13 Additionally, the NBRC funds project pre-development through the North Country Council (NCC), including technical assistance and capacity building to support successful grant applications and initial project implementation. This complements U.S. Economic Development Administration funds that support the North Country Economic Development Strategy Committee, which is tasked with bringing key stakeholder groups together to develop a regional economic development plan, by helping to translate the plan into action.14 Carsey researchers on the CERA and Coös Youth Study projects presented findings to the committee in January 2018 to inform their strategic planning.

- The New Hampshire Broadband Mapping and Planning Program at the University of New Hampshire completed the Broadband in Coös County Project with sponsorship from the NBRC in 2015–2016.15 This project identified service gaps and worked with community leaders and local agencies to develop a broadband expansion plan. Coös County was found to have the third highest percentage of undeserved population in New Hampshire at 16.9 percent, following 18.7 percent in Sullivan County and 23.5 percent in Cheshire County.16 A follow-up 2016–2018 project, Broadband in Northern New Hampshire, sought to address broadband access, affordability, and use in Coös and other underserved New Hampshire counties to support regional economic development.17 BroadbandNow reports that approximately 70 percent of Coös residents have access to 100-plus mbps internet service, compared to over 97 percent of residents in Rockingham, Strafford, Hillsborough, and Belknap Counties.18 However, even this figure of 70 percent, as well as the industry definition of “access,” has been questioned by local stakeholders with whom the findings did not resonate. New cell towers and wireline service have improved access to high-speed internet in Coös over the last decade, but more work is still needed to improve access and utilization.19

Coös leaders from a broad range of sectors are prepared to work to collectively move the region forward, but there is some resistance to change, and a balance needs to be achieved between local and regional approaches.

From 2009 to 2011, Carsey researcher Michele Dillon interviewed fifty-one Coös County community leaders from a broad range of sectors for a qualitative case study of social capital and community change. She also conducted a community leader survey, attended the Coös Symposium20 as a participant-observer, and reviewed documentary evidence such as newspaper articles, meeting minutes and agendas, and organizational reports. Dillon found that most community leaders were personally and deeply committed to the region, with some describing a calling or responsibility for community well-being or a powerful drive to use their skills and talents to give back to their communities. Many participated in local organizations and voluntary associations beyond their leadership roles. These findings are consistent with CERA survey results characterizing Coös County as a place where people are willing to help their neighbors and work together to address issues, as well as with findings from the Coös Youth Study that will be described later in this report.

Dillon’s case study represented a group of people keenly aware of the challenges faced by the region and ready to work to help their communities survive what they described as a social and economic crisis. But barriers to making progress were also noted. For example, participants referred to a confusing array of nonprofit economic development organizations creating inefficiencies and confusion for those seeking business assistance. They saw physical infrastructure in need of maintenance and repair. They voiced concerns about the reputational costs of speaking out against established parties and policies in their small-town environments where everyone knows everyone else by name, as well as the actual costs in the case of business owners. They questioned whether the region’s leadership was prepared to tackle the substantial issues of the day. These findings are consistent with CERA surveys at all three time points finding that fewer than half of Coös residents believe that state and local government can deal effectively with important problems.

Historically, geographically isolated rural communities were self-sufficient by necessity, a situation that reinforced their economic, social, and cultural isolation. However, Dillon argues that rural communities may be better served by increased regionalism now that the mills no longer serve as the economic pillars for segments of the county. Efforts that bring to bear the resources and assets of the entire county may be more successful in sustaining public services and infrastructure for a smaller and more disperse population, and in attracting tourism and industry to the region, to the benefit of all. For example, New Hampshire Grand, launched in 2009 by the Northern Community Investment Corporation (NCIC), promoted the entire North Country’s recreational amenities to the public, without the limits of Chamber of Commerce catchment areas or even county lines. It recognized that tourists visiting the amenity-rich neighbor to the south, Grafton County, are unlikely to be mindful of the political boundary if there is an attraction of interest nearby in Coös. This level of inter-community cooperation in rebranding the post-manufacturing economy did not happen by accident. It took significant efforts on the part of NCIC staff and other project stakeholders to bring traditionally competing entities to the consensus that the advantages of a regional approach outweighed the threats. It will take continued investment of time and resources for the benefits of such initiatives to be sustained.

Community attachment has emerged as a key factor for youth well-being and future plans.

The Coös Youth Study’s interdisciplinary research team comprised two professors of sociology, Cesar J. Rebellon and Karen T. Van Gundy, and two professors of human development and family studies, Erin Hiley Sharp and Corinna Jenkins Tucker. They explored such topics as the home, school, and community environments, family and social relationships, extra-curricular activity participation, mental health and substance use, and decisions regarding outmigration. A common theme emerged: community attachment is an important factor in both youth well-being and youth retention. In other words, it has both individual and community-level implications.

What do we mean by community attachment?21 The Coös Youth Study survey included an original measure of community attachment asking participants to rate from strongly disagree to strongly agree such statements as “my community is safe,” “I care about my community,” and “my community has caring, friendly, helpful people.” Among youth in grades 7 and 11, high rates of Coös County students (72 to 89 percent) agreed or strongly agreed with these positive statements about their community. Again, there was cross-study confirmation regarding the strong social connections of this region, and new evidence that youth could be counted among those participating in and benefiting from this aspect of Coös community life. The most recent Coös Youth Study survey, conducted in 2017–2018, found that, whether participants still lived in Coös or had moved elsewhere, large majorities—89 percent and 68 percent, respectively—said that they still cared about issues and events in the county.

Coös Youth Study researchers have found that youth with a stronger sense of community do better academically, emotionally, and behaviorally.22 They found that community attachment in youth is associated with lower risk of co-occurring symptoms of depressed mood and substance misuse in adulthood.23 Broadening the definition of community attachment, other Coös Youth Study research has found participation in out-of-school activities to be associated with higher grades, a stronger sense of belonging at school, and more positive expectations for the future.24 It has also found that youth with adult mentors in their lives are more likely to enjoy their academic subjects at school and to have higher aspirations.25

An exception to the positive findings from the measure of community attachment is found in response to the statement, “people in this community care what kids think,” which garnered the agreement of only just over half of participants in early Coös Youth Study surveys. This concern is echoed in multiple participants’ comments, for example:

I feel that like the older generations…don’t want a huge change. They just want it to stay little ol’ [Coös] and they don’t want to change anything that would help them.…It’s really sad. They’re stunting their own growth.”26

Coös Youth Study researchers found that participants who felt as if their voices were heard as youth were more likely to report that they wanted to make Coös County their permanent place of residence in the future, even if they had left for a period of time to pursue academic or occupational opportunities outside the region.27 This outcome speaks to the critical importance of youth voice in youth retention efforts.

Conclusions

In the ten-plus years that the Tracking Change in the North Country project has been underway, Coös County has stabilized somewhat from its manufacturing losses but continues to straddle the perils of manufacturing decline and the potential of amenities-based growth. Many of the recommendations from the original CERA report in 2008 remain important today. Physical and technological infrastructure investments are still necessary to address the needs of the current population and to attract tourists, new residents, and new industries. Workforce development and the continuous fostering of education and workforce pathways will still help to ensure that all young people in Coös can envision a successful future for themselves, whether they stay in the region, permanently relocate, or leave to pursue educational and professional opportunities and later return with new skills and new ideas to share with their communities.

The Tillotson Fund’s Early Childhood Development initiative offers evidence that regional approaches have already yielded benefits for the area. As an additional example, with support from the NBRC, the Tillotson Fund, the U.S. Department of Agriculture Office of Rural Development, and other funders, Bike the Borderlands promotes mountain biking trails across New Hampshire, Maine, Vermont, and Southern Quebec. The Coös Symposia offered a regional networking event, catalyzing the resources and ideas of stakeholders across multiple sectors and serving as an example of how regional organizations can serve as what Dillon referred to as “social capital brokers.” The social capital is already present in large supply but requires bridging across the county’s unique communities. Continued encouragement of regional approaches should be considered as an investment in the future of Coös.

As important as regionalism may be to the future of the Coös County, it is clear from all areas of Tracking Change research that the strength of local communities remains an important asset. Indeed, community attachment is driving leaders to put time and resources into regional recovery, and it is resulting in more positive outcomes for youth. However, youth have also reported they do not feel they have much of a voice in Coös County communities. The Tillotson Fund responded by giving young people a seat at the table in planning for the region’s future. Its Empower Coös Youth Grantmaking Program offered a committee comprised of local high school students the opportunity to review grant proposals using criteria of their own design, reflecting their priorities for the future of Coös. Informed by the Coös Youth Study findings, the committee emphasized programs that support environmental initiatives, offer extracurricular activities for youth, and strengthen community engagement.

The findings also converge on Coös County as a place where there is some resistance to change, and where new ideas are viewed with some suspicion. It is understandable that long-time residents are concerned about losing the area’s special character and natural beauty. Lean too much to one side, and the most cherished aspects of the region are lost to generic development and environmental degradation. Lean too far to the other, and the region stagnates or, worse, slips further into decline. The challenge to leadership is to hear and consider new ideas from young people—those who leave but later return with fresh perspectives, as well as recent arrivals—and weigh them against the significant concerns about stewardship of natural and cultural resources.

Box 1: The Four Rural Americas

In their report, “Place Matters: Challenges and Opportunities in Four Rural Americas,” Carsey researchers Larry Hamilton, Leslie Hamilton, Mil Duncan, and Chris Colocousis countered stereotypes of American rurality—small farms, church on Sunday, the simple life—by developing a framework distinguishing four distinctive types of rural places: amenity-rich, declining resource-dependent, chronically poor, and amenity/decline. Regions within each type share a set of characteristics and a similar apparent trajectory.

Amenity-rich rural America: Often appearing on postcards or artists’ canvases, the rugged mountains, deep forests, cool lakes, rocky coastlines, and other wild, less crowded landscapes make amenity-rich places attractive. Drawn by images of quiet, small-town community life, three out of five baby boomers would like to move here, many to retire. Meanwhile, more people buy second homes in rural communities. Affluent professionals settle in conveniently located small towns amid natural splendor, yet close to large cities where they commute for work or entertainment and cultural amenities. Less affluent young, upwardly mobile professionals move in to raise their children in safe, small town environments. Property values rise and the mix of businesses changes when newcomers want new services and can afford higher prices. But what happens to the “old-timers” or those working residents who are priced out of their own neighborhoods?

Declining resource-dependent rural America:These are places that once depended almost solely on agriculture, timber, mining, or related manufacturing industries to support a solid, blue-collar middle class. Many of these communities have a long history of booms and busts, and now that resources are depleted and low-skill manufacturing jobs are threatened by globalization, they are in economic decline. Populations are declining, although some of these areas have seen new immigrants arrive, willing to work at low-skill, low paying jobs. The once-vibrant middle class, so important to strong community institutions, is threatened. What happens as property values plummet, schools are challenged as young adults leave, new populations move in, and long-time residents cannot afford to move out?

Chronically poor rural America: The chronically poor regions are rich in history, but it is a history of devastating hardship. Here, both residents and the land have experienced decades of resource depletion and underinvestment, leaving behind broken communities with dysfunctional services, inadequate infrastructure, and ineffective or corrupt leadership. Generations of families have been held back by inadequate education and weak civic institutions. As the population suffers, so does the environment, and the downward spiral continues. With little or nothing to attract newcomers, and only the occasional flood or mining disaster to bring national attention, these communities are largely ignored and forgotten. What strategies and new directions will work in these areas and where will funding and human capital to reinvigorate these communities come from?

Amenity/decline rural America: The amenity/decline places represent a transitional type, with similarities to both amenity-rich and declining resource-dependent communities. The traditional resource-based economies of these places have weakened but not vanished, and their aging populations reflect out-migration. At the same time, these areas show signs and potential for amenity-based growth.

Endnotes

1. This commitment is in keeping with the mission of the Neil and Louise Tillotson Fund and established by the Tillotson Trustees.

2. After the Fraser Papers closure, this mill reopened in 2012 under new ownership as Gorham Paper and Tissue. Since then it has been operating intermittently with varying numbers of employees and has struggled to pay off back taxes and loans from the town. See, e.g., Christopher Jensen, “Gorham Paper & Tissue Is Making Progress Paying Off Debt,” InDepthNH.org, January 15, 2017, http://indepthnh.org/2017/01/15/gorham-paper-tissue-is-making-progress-…). See also New Hampshire Economic Security, “Coös County Perspectives: The Groveton Mill Closures,” 2007, https://www.nhes.nh.gov/elmi/products/documents/cooscounty-groveton.pdf.

3. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Regional GDP & Personal Income Table CA25N: Total Full-Time and Part-Time Employment by NAICS Industry,” https://www.bea.gov/.

4. New Hampshire Employment Security Economic & Labor Market Information Bureau, Community Profiles by County, “Coös County,” https://www.nhes.nh.gov/elmi/products/cp/documents/coos-cp.pdf.

5. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Regional GDP & Personal Income Table CA25N.”: Total Full-Time and Part-Time Employment by NAICS Industry,” https://www.bea.gov/.

6. The New Hampshire meals and rooms tax was 9 percent as of July 1, 2009 and remained at 9 percent throughout the period of analysis.

7. Telephone communication with Pamela LaFlamme, City of Berlin Community Development Director. Corroborating U.S. Census Bureau data will not be available until 2020 Census results are published.

8. K. Bundschuh, “The Benefits and Barriers to Living in Coös County: Perceptions of the Region From Emerging Adults” (manuscript submitted for publication, 2019).

9. M. Dillon, “Stretching Ties: Social Capital in the Rebranding of Coös County, New Hampshire,” Scholars’ Repository Paper 149 (Durham, NH: Carsey Institute at the Scholars’ Repository, University of New Hampshire, 2011); M. Dillon, “Forging the Future: Community Leadership and Economic Change in Coös County, New Hampshire” (Durham, NH: Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire, 2012).

10. See, for example, the following press releases and news articles: https://www.shaheen.senate.gov/news/press/shaheen-berlin-prison-opening…, http://www.sunjournal.com/berlin-nh-eyes-prison-jobs-logging-revive-eco…, http://www.unionleader.com/article/20121022/NEWS07/710229969&template=m…, http://www.nhpr. org/post/sound-money-can-atvs-reinvigorate-nhs-north-country-economy#stream/0, https://www.boston.com/news/local-news/2017/11/04/atv-tourists-in-north….

11. Bundschuh (2019).

12. This philanthropic and community success is detailed in L.P. Simon, K. Scobie, P. Backler, C. McDowell, C. Cotton, S. Cloutier, and C. Nolan, “By Us and for Us: A Story of Early Childhood Development Systems Change and Results in a Rural Context,” Foundation Review 10, no. 4 (2018), https://doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1441.

13. Northern Border Regional Commission, “2018 Northern Border Regional Commission Annual Report” (n.d.), http://www.nbrc.gov/uploads/003%20IMPACT%20%26%20%20REPORTING/Annual%20Reports/NBRCAnnualReport2018.pdf.

14. Northern Border Regional Commission, “New Hampshire Investments, 2016” (n.d.), http://www.nbrc.gov/uploads/State%20New%20Hampshire/2016.pdf.

15. University of New Hampshire Broadband Center of Excellence, “Completed Projects: Broadband in Coös County” (n.d.), https://www.unh.edu/broadband/completed-projects.

16. New Hampshire Broadband Mapping & Planning Program and the University of New Hampshire, “2016 Broadband Report: Coös County, New Hampshire,” 2016, https://iwantbroadbandnh.org/sites/default/files/planning/NBRC%20Final%20Report-V5.pdf.

17. New Hampshire Broadband Mapping & Planning Program, “Current Projects: Broadband in Northern New Hampshire” (n.d.), https://iwantbroadbandnh.org/current-projects.

18. Broadband Now, “Internet Access in New Hampshire” (n.d.), https://broadbandnow.com/New-Hampshire.

19. Email communication with Fay Rubin, project director of the New Hampshire Geographically Referenced Analysis and Information Transfer System (NH GRANIT) at the University of New Hampshire Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space, May 2, 2019.

20. The Coös Symposia were annual multiday meetings organized and supported by the Tillotson Fund to foster relationships and cross-sector thinking at the county level. They are no longer held on a regular basis, although the fund is engaged in other regional initiatives that bring stakeholders together to address shared goals.

21. The community attachment measure was informed by items from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2004) and by the work of Charlotte Fabiansson (C. Fabiansson, “Being Young in Rural Settings: Young People’s Everyday Community Affiliations and Trepidations,” Rural Society 16 (2006): 47–61).

22. C. Rebellon, “When We Foster a Sense of Community, Everybody Wins,” in E.M. Jaffee, C.J. Tucker, K.T. Van Gundy, E.H. Sharp, and C.J. Rebellon, “Northern New Hampshire Youth in a Changing Rural Economy: A Ten-Year Perspective,” Reports on New England No. 5 (Durham, NH: Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire, 2019).

23. K.T. Van Gundy, “Mental Health, Social Stress, and Sense of Community,” in Jaffee et al. (2019).

24. E.H. Sharp, “Out-of-School Time Matters: Activity Involvement and Positive Development Among Coös County Youth,” New England Issue Brief No. 17 (Durham, NH: Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire, 2010).

25. K. Scovill and C.J. Tucker, “Coös Youth With Mentors More Likely to Perceive Future Success,” Regional Fact Sheet No. 9 (Durham, NH: Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire, 2013).

26. Bundschuh (2019).

27. Rebellon (2019).

About the Author

Eleanor M. Jaffee, Ph.D., Evaluation Program Director at the Carsey School of Public Policy, served as the Coös Youth Study project manager from 2010 through 2019. In this role, her focus was on participant retention in the 10-year study. She also strived to bring the study’s findings to North Country stakeholders with the potential to translate them into practice on a regular basis. In August of 2019, Eleanor launched Insights Evaluation, LLC, an evaluation and applied research consulting company based in Manchester, New Hampshire. She can be contacted at eleanor.jaffee@unh.edu or eleanor.jaffee@insightsevaluation.com.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Kirsten Scobie, Phoebe Backler, and all the members of the Neil and Louise Tillotson Fund Advisory Committee at the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation; Pamela LaFlamme, City of Berlin Community Development Director; Michelle Moren-Grey, Co-Executive Director & Chief Executive Officer of the North Country Council; Michael Ettlinger, Curt Grimm, Michele Dillon, Jessica Carson, and Laurel Lloyd at the Carsey School of Public Policy; and Patrick Watson for editorial assistance. She also acknowledges the impressive body of work amassed by the many researchers and student research assistants for these Carsey School research projects, including but not limited to Chris Colocousis, Michele Dillon, Mil Duncan, Curt Grimm, Larry Hamilton, Leslie Hamilton, Cesar Rebellon, Erin Hiley Sharp, Corinna Jenkins Tucker, and Karen Van Gundy.

Related Reading

- Colocousis, C., Hamilton, L., & Hamilton, L. R. (2008). Place Matters: Challenges and Opportunities in Four Rural Americas (Reports on Rural America, Vol. 1, No. 4). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Bundschuh, K. (2019). The Benefits and Barriers to Living in Coös County: Perceptions of the Region from Emerging Adults. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Simon, L. P., Scobie, K., Backler, P., McDowell, C., Cotton, C., Cloutier, S. & Nolan, C. (2018). By us and for us: A story of early childhood development systems change and results in a rural context. The Foundation Review, 10(4), Article 6. https://doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1441

- Dillon, M. (2011). Stretching Ties: Social Capital in the Rebranding of Coös County, New Hampshire (New England Issue Brief No. 27). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Dillon, M. (2012). Forging the Future: Community Leadership and Economic Change in Coös County, New Hampshire (Carsey Institute Report). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Jaffee, E. M., Tucker, C. J., Van Gundy, K. T., Sharp, E. H., & Rebellon, C. (2019). Northern New Hampshire Youth in a Changing Rural Economy: A Ten-Year Perspective (Reports on New England No. 5). Durham, NH: The Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire.

- Sharp, E. H. (2010). Out-of-school Time Matters: Activity Involvement and Positive Development among Coös County Youth (New England Issue Brief No. 17). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Scovill, K. & Tucker, C. J. (2013). Coös Youth with Mentors More Likely to Perceive Future Success (Regional Fact Sheet No. 9). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

All Tracking Change Carsey Research Products

Tracking Change

- Hamilton, L. C., Fogg, L. M., & Grimm, C. (2017). Challenge and Hope in the North Country (National Issue Brief No. 130). Durham, NH: The Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire.

- Dillon, M. (2012). Forging the Future: Community Leadership and Economic Change in Coös County, New Hampshire (Carsey Institute Report). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Colocousis, C. & Young, J. (2011). Continuity and Change in Coös County: Results from the 2010 North Country CERA Survey (New England Issue Brief No. 26). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Colocousis, C. & Hartter, J. N. (2011). Environmental, Economic, and Social Changes in Rural America Visible in Survey Data and Satellite Images (Issue Brief No. 23). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Dillon, M. (2011). Stretching Ties: Social Capital in the Rebranding of Coös County, New Hampshire (New England Issue Brief No. 27). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Dillon, M. & Young, J. (2011). Community Strength and Economic Challenge: Civic Attitudes and Community Involvement in Rural America (Issue Brief No. 29). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Colocousis, C. R. (2008). The State of Coös County: Local Perspectives on Community and Change (New England Issue Brief No. 7). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Colocousis, C., Hamilton, L., & Hamilton, L. R. (2008). Place Matters: Challenges and Opportunities in Four Rural Americas (Reports on Rural America, Vol. 1, No. 4). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

Coös Youth Study

- Jaffee, E. M., Tucker, C. J., Van Gundy, K. T., Sharp, E. H., & Rebellon, C. (2019). Northern New Hampshire Youth in a Changing Rural Economy: A Ten-Year Perspective (Reports on New England No. 5). Durham, NH: The Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire.

- Jaffee, E. M., Staunton, M. (2014). Key Findings and Recommendations from the Coös Youth Study (Issue Brief No. 41). Durham, NH: The Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire.

- Seaman, J. O., McLaughlin, S. R. (2014). The Importance of Outdoor Activity and Place Attachment to Adolescent Development in Coös County, New Hampshire (Issue Brief No. 37). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Tucker, C. J. (2014). Levels of Household Chaos Tied to Quality of Parent-Adolescent Relationships in Coös County, New Hampshire (Issue Brief No. 42). Durham, NH: The Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire.

- Scovill, K. (2013). Sixty Percent of Coös Youth Report Having a Mentor in Their Lives (New England Fact Sheet No. 8). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Tucker, C. J., Scovill, K. (2013). Coös Youth with Mentors More Likely to Perceive Future Success (Regional Fact Sheet No. 9). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Van Gundy, K. T. (2013). Comparing Teen Substance Use in Northern New Hampshire to Rural Use Nationwide (Issue Brief No. 34). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Van Gundy, K. (2013). Mental Health Among Northern New Hampshire Young Adults: Depression and Substance Problems Higher Than Nationwide (Issue Brief No. 35). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Jaffee, E. M. (2012). Coös County’s Class of 2009: Where Are They now? (Issue Brief No. 31). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Sharp, E. H. (2012). Coös County Youth and Out-of-School Activities - Patterns of Involvement and Barriers to Participation (New England Fact Sheet No. 7). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Sharp, E. H. (2012). Youths’ Opinions About Their Opportunities for Success in Coös County Communities (New England Fact Sheet No. 6). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Tucker, C. J., Wiesen-Martin, D. (2012). Coös County Teens’ Family Relationships (New England Fact Sheet No. 5). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Young, J. (2012). It Takes a Community: Civic Life and Community Involvement Among Coös County Youth (Issue Brief No. 32). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Cox, G. R., Tucker, C. J. (2011). No Place Like Home: Place and Community Identity Among North Country Youth (Issue Brief No. 24). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Tucker, C. J., Cox, G. R. (2011). Coös Teens’ View of Family Economic Stress Is Tied to Quality of Relationships at Home (Issue Brief No. 28). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Van Gundy, K. T., Mills, M. L. (2011). Teen Stress and Substance Use Problems in Coös: Survey Shows Strong Community Attachment Can Offset Risk (Issue Brief No. 29). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Mills, M. L., (2010). Help in a Haystack: Youth Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services in the North Country (Issue Brief No. 20). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Rebellon, C. J., Stracuzzi, N. F., Burbank, M. (2010). Youth Opinions Matter: Retaining Human Capital in Coös County (Issue Brief No. 19). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Sharp, E. H. (2010). Out-of-School Time Matters: Activity Involvement and Positive Development among Coos County Youth (Issue Brief No. 17). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Sharp, E. H. (2010). Too Much Free Time: Coos County Youth Who Are Least Involved in Out-of-School Activities Are Most Likely to Use Drugs & Alcohol (Issue Brief No. 18). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Stracuzzi, N. F., Mills, M. L. (2010). Teachers Matter: Feelings of School Connectedness and Positive Youth Development Among Coos County Youth (Issue Brief No. 23). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Shattuck, A. (2009). Navigating the Teen Years: Promise and Peril for Northern New Hampshire Youth (Issue Brief No. 12). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Stracuzzi, N. F. (2009). Youth Aspirations and Sense of Place in a Changing Rural Economy: The Coös Youth Study (Issue Brief No. 11). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.

- Tucker, C. J. (2009). Stay or Leave Coös County? Parents’ Messages Matter (Issue Brief No. 14). Durham, NH: The Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.