download the brief

Key Findings

Policy makers and advocates nationwide recognize that funding for early childhood education is a crucial investment in the future. Critical foundational development occurs before age 5, and research consistently shows that high-quality early education for children leads to higher future educational attainment and lower likelihood of crime,1 and yields a return on investment of 7 to 13 percent.2

Yet accessing affordable, quality early childhood education and care is a challenge for families nationwide. More than a quarter of families with young children are burdened by child care costs,3and the availability and quality of child care and education are highly variable across states.4

One program that connects the most economically vulnerable families with quality early childhood programming is Early Head Start (EHS). Subject to rigorous quality and staffing standards,5 implemented among the youngest children (prenatally through age 2), and delivered via a two-generation approach, EHS is a significant opportunity for providing quality care and education to a population that might otherwise struggle to access it. This brief explores the characteristics of EHS in Maine, compares them to the national landscape, and connects these findings to a discussion of the federal and state policy climates.

Home Visitation Model Popular in Maine

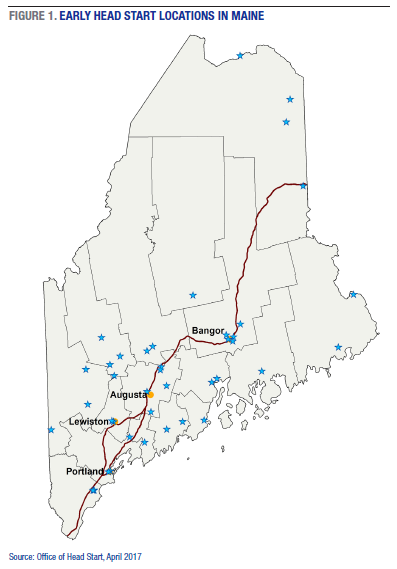

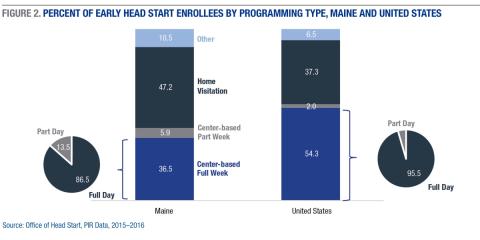

EHS programming is offered in forty-four sites in Maine.6 Each of Maine’s sixteen counties has at least one site, though the distribution roughly mirrors the state’s population concentration, with more sites in the southern and eastern parts of the state (see Figure 1).Nearly half (47.2 percent) of Maine children7 in EHS are enrolled in home visitation programming, a well-regarded model that includes weekly 90-minute visits and twice-monthly group activities for enrolled parents and children.8 This compares with 37.3 percent of children in EHS nationwide (Figure 2). Maine children are less often enrolled in EHS full-week, center-based programming than are children nationwide (36.5 percent versus 54.3 percent), although most children attending full-week also attend full-day, both in Maine and across the nation. A small share of children is enrolled in center-based, part-week programming, and a smaller share is enrolled in “other” programming including family-based care, locally designed options, or other offerings.

EHS Serves Many Working Families

Although EHS programming is primarily targeted to families with incomes below the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services federal poverty guideline ($24,600 for a family of four in 2017),9 EHS enrollees have a diverse set of family employment conditions. Seventy percent of Maine EHS enrollees in two-parent families have at least one working parent, and 38.2 percent have at least one parent in job training or school (compared with 83.6 percent and 23.9 percent nationwide). Among Maine EHS children living with a single parent, about half have a working parent and about a fifth have a parent in school or job training (both similar to national rates).

Maine EHS Compares Favorably to National Trends in Some Regards, Less Well in Others

Although it is a mostly federally funded program,10 there is considerable state-to-state variation in EHS funding11 and characteristics.12 Maine EHS programs compare favorably in some regards; for example, Maine staff are relatively highly educated, with more than 37.5 percent of center-based teachers and 65.1 percent of home visitors having at least a four-year college degree, compared with 25.4 percent and 54.6 percent nationwide.13 In addition, Maine children who age out of EHS demonstrate a continuing attachment to early childhood care and education: 94 percent of Maine toddlers who aged out of EHS in 2015–2016 entered another early childhood program, compared with just 84 percent of toddlers nationwide.

On other dimensions, however, the state compares less favorably. The most important shortfall is the limited reach of EHS programming among its target population. Maine has 837 funded EHS slots, but Census estimates show that more than 8,000 Maine children age 0–2 live below the poverty line.14 Though Maine reaches a higher share of poor young children (around 10 percent) than does EHS programming at the national level (close to 5 percent), the number of existing slots is inadequate for reaching all eligible young Mainers.

In addition, the low share of full-week/full-day enrollment means that Maine EHS children may have fewer average hours of contact with quality programming, and even parents whose children are enrolled may still struggle to meet child care needs.15 Further, although the pipeline is strong for children who remain enrolled in the program, a considerable share of children leave Maine EHS programming before they age out and do not re-enroll16—35.9 percent in Maine compared with 30.9 percent nationwide. Given EHS’s already limited reach, that more than one in three Maine enrollees exit programming before aging out is particularly worrisome.

Policy Implications

For families nationwide, finding quality and affordable early childhood care and education are pressing concerns. A funding bill passed by Congress in May 2017 provides EHS programs with a cost-of-living funding increase for fiscal year 2017, but there are no plans to expand the program to reach more children and families.17 Nor is there any indication that the current federal administration intends to grow the child care assistance program, even though it serves only one of every seven federally eligible children.18 Thus, the child care system—both in Maine and nationwide—is already strained, and EHS in particular does not have the funds to reach all poor children and families who might benefit from its quality programming.

Maine’s EHS programming serves an important segment of the vulnerable population, including the state’s youngest children, all of whom are facing some kind of economic or social disadvantage. Nearly half of Maine EHS families are receiving home visitation services—an approach that research shows is especially effective19 and which is all the more important because the state’s capacity to deliver home-visiting services in other ways is shrinking.20 Further, given Maine’s rising infant mortality rate,21 opportunities to connect young mothers with in-home services could have important implications for subsequent pregnancies.

In addition, a high share of these families relies on the social safety net more broadly. Therefore, existing challenges around providing quality early childhood education and care could be exacerbated by cuts not only to Head Start but to other programs as well. For instance, policy and administrative changes being considered in Washington could lower access to health insurance coverage, reduce funds that help low-income families cover winter heating costs, and cut funding for nutrition programs. These changes could reduce economic stability and undermine parents’ efforts to provide their children with a strong start in their earliest years.

Although state supplemental funds pay for a small share of all Maine EHS slots (60 of the 837 slots in 2015–2016), in a climate where early childhood education and care is expensive, these slots provide critical access to some of Maine’s most vulnerable families. More broadly, because EHS can reach only a small number of Mainers, the state legislature might consider ways to bolster the stability of this population in other ways, including through state home visitation funds and child care funds more generally. These efforts can help maintain and expand critical access to quality early childhood education and care—including through EHS—in order to better serve the needs of Maine’s working families.

Data

Data used in this brief are drawn from the Office of Head Start’s Program Information Reports, the program’s mandated data collection system. It is important to note that these data are collected from each program via self-report from program staff, and, as such, interpretation of report items may vary between program staff or program site. Program-related data (for example, on program option) refer to funded enrollment (that is, “program slots”) and not necessarily to individual children. Note that the “universe” of enrollees varies slightly across measures, with some measures not being collected among all enrollees (more detail available from author upon request). Data are presumed to be accurate as of the date of collection, although staff, program, and enrollee characteristics might change over the program year. See https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/hslc/data/pir for more information about the Office of Head Start’s data collection procedures.

Endnotes

1. See, for example, “Early Childhood Education,” National Education Association, http://www.nea.org/home/18163.htm.

2. “Invest in Early Childhood Development: Reduce Deficits, Strengthen the Economy,” Heckman Equation Project, https://heckmanequation.org/assets/2013/07/F_HeckmanDeficitPieceCUSTOM-G....

3. Marybeth J. Mattingly, Andrew Schaefer, and Jessica A. Carson, “Child Care Costs Exceed 10 Percent of Family Income for One in Four Families,” Issue Brief No. 109 (Durham, NH: Carsey School of Public Policy, 2016).

4. See Dionne Dobbins et al., “Child Care Deserts: Developing Solutions to Child Care Supply and Demand” (Arlington, VA: ChildCare Aware of America, 2016), http://usa.childcareaware.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Child-Care-Dese... W. Steven Barnett et al., “The State of Preschool 2015: State Preschool Yearbook” (New Brunswick: National Institute for Early Education Research, Rutgers Graduate School of Education, State University of New Jersey, 2016), http://nieer.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Yearbook_2015_rev1.pdf.

5. See “Policy and Regulations,” Office of Head Start, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ohs/policy.

6. See “Head Start Locator,” Early Childhood Learning and Knowledge Center, Office of Head Start, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/hslc/HeadStartOffices. Note that the program locator shows forty-eight EHS locations in Maine, but this count includes four duplicate listings, each for sites with an EHS Child Care Partnership (Kennebec Valley Community Action Program and York Community Action Corporation).

7. “Children” and “enrollees” are used interchangeably in this brief; although a small share of Maine enrollees are pregnant women (6%), this population is not the focus here.

8. “Implementing Early Head Start-Home Visiting (EHS-HV): Program Model Overview,” Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, homvee.acf.hhs.gov/Implementation/3/Early-Head-Start-Home-Visiti....

9. See “Poverty Guidelines,” Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, https://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines.

10. For the 2015–2016 year, the Office of Head Start data show that 7 percent of Maine’s EHS slots were funded with non-Administration for Children and Families funds, a category that includes state or local funds.

11. The formula by which federal funds are allotted for Head Start and Early Head Start programming is complex, and exploration of this formula is beyond the scope of this brief. However, for a discussion of how these funds are allotted in one state in particular (California) and more about the allotment process generally, see Tim Ransdell and Shervin Boloorian, “Federal Formula Grants and California: Head Start” (San Francisco, CA: Public Policy Institute of California, 2003), http://www.ppic.org/content/pubs/ffg/FF_1003TRFF.pdf.

12. The Office of Head Start collects classroom quality data via the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) Pre-K-Teacher-Child Observation Instrument among its grantees. Because these data do not apply to, and are not collected among, EHS grantees, it is difficult to assess EHS program quality here, aside from staff education.

13. Recent research shows a correlation between classroom quality and teacher educational attainment, specifically when comparing quality among teachers with a bachelor’s degree or more to teachers with less education. See Pamela Kelley and Gregory Camilli, “The Impact of Teacher Education on Outcomes in Center-Based Early Childhood Education Programs: A Meta-Analysis” (New Brunswick, NJ: National Institute for Early Education Research, 2016), http://nieer.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/TeacherEd.pdf.

14. Author’s analysis of American Community Survey 2015, five-year microdata (IPUMS-USA, University of Minnesota, www.ipums.org). Note that this calculation uses five years of Census data to accurately estimate the number of poor, very young children in Maine, so the time periods for funded enrollment and poor children differ (2015–2016 program year versus 2011–2015 ACS data). Also note that data do not allow for estimation of the number of poor pregnant women, so the target population is actually larger than that listed here. The Census estimation of poor children uses the statistical definition of poverty, rather than the Department of Health and Human Services version, so there is slight variation between those thresholds. Finally, because poverty is not the only indicator of eligibility (others include homelessness and foster child status), the universe of eligible potential enrollees in Maine is much higher than the estimated number of poor. Following a report from the National Institute for Early Education Research (W. Steven Barnett and Allison H. Friedman-Krauss, “State(s) of Head Start” [New Brunswick: National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER), Rutgers Graduate School of Education, State University of New Jersey, 2016]), I also calculate Maine’s programming reach among very young children with incomes below 200 percent of the poverty line (“low income” children) and find that the program has the potential to reach 4.8 percent of low-income children in Maine. This estimate is slightly higher than the estimate from the NIEER report (4.0 percent), likely due to the differing time periods used in each calculation, although the point remains that funded enrollment is inadequate.

15. There is some evidence that higher numbers of contact hours with quality early childhood education programming produce better outcomes for children, although research also notes that parents’ decisions to enroll their children in part-time versus full-time programming are not random, and potential effects could be related to parental characteristics rather than to characteristics of the programming per se (see Thomas van Huizen and Janneke Plantenga, “Universal Child Care and Children’s Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis of Evidence From National Experiments,” Working Paper Presented at the Annual Fall Research Conference of the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management, Miami, FL, November 2015). However, unlike program intensity, there is research consensus on the importance of program quality, and the quality of EHS programming is strictly regulated. As such, for working parents struggling to find affordable and quality child care, the availability of full-day, full-week slots could be an influential factor in their capacity to find and retain work.

16. These data do not reveal why children unenroll from EHS programming, although it is possible that issues like transportation and complex family work schedules, which affect low-income families more generally, may come into play.

17. See “America First: A Budget Blueprint to Make America Great Again” (Office of Management and Budget, 2017), https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/budget-united-states-government-54/fiscal-year-2018-539812.

18. Lecia Imbery, “Fact of the Week: Number of Children Benefiting from Federal Low-Income Child Care Program at 17-Year Low,” Coalition for Human Needs, http://www.chn.org/2017/02/28/fact-of-the-week-number-of-children-benefi....

19. EHS home visiting meets Department of Health and Human Services criteria for an “evidence-based” home visiting service delivery model. These kinds of evidence-based programs generally and EHS specifically have been associated with a host of favorable child and family impacts, including school readiness and positive parenting practices. For more details, see Emily Sama-Miller et al., “Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness Review: Executive Summary” (Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Evaluation, and Research, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016), https://homvee.acf.hhs.gov/HomVEE_Executive_Summary_2016_B508.pdf.

20. Maine’s public health nurses also deliver home visiting services to Maine children and families, although, according to the Bangor Daily News, the number of public health nurses in Maine has been halved since 2009. See Matthew Stone, “Maine Has Sliced the Ranks of Nurses Who Prevent Outbreaks, Help Drug-Affected Babies,” Bangor Daily News, August 9, 2016, http://bangordailynews.com/2016/08/09/mainefocus/maine-has-sliced-the-ra....

21. Maine’s infant mortality rate was ranked number 31 of the 50 states and Washington, DC in 2015. The state’s infant mortality rate has risen sharply in recent years, and was lowest in the nation as recently as 2002. See “Infant Mortality,” Kids Count Data Center (http://datacenter.kidscount.org/).

Acknowledgements

This brief was funded by the John T. Gorman Foundation. The author thanks Carsey School colleagues Beth Mattingly, Michele Dillon, Curt Grimm, Michael Ettlinger, and Amy Sterndale for reviewing earlier drafts, and Laurel Lloyd and Bianca Nicolosi for their layout assistance. Additional thanks to Patrick Watson for editorial assistance.