download the brief

Key Findings

Dating Violence Among High School Teens

Dating violence, defined as physical abuse (such as hitting) or sexual abuse (such as forcible sexual activity) that happens within the context of a current or former relationship, leads to a host of negative consequences, including poor mental and physical health and academic difficulties.1 Therefore, it is important that researchers examine factors that increase or decrease risk for dating violence, and then use this research to create evidence-based prevention and risk reduction efforts.

To date, researchers have primarily focused on individual factors (for example, attitudes toward violence) and relational factors (such as peer group norms) that may be related to dating violence victimization.2 However, it is also important to examine school and community characteristics that may serve as risk or protective factors for dating violence3 and to understand which youth may be at the highest risk for dating violence victimization.

Overall Rates of Dating Violence Among Teens in New Hampshire

Nearly one in ten teens (9.1 percent) in New Hampshire reported being the victim of physical dating violence during the past year; across the 71 schools studied, the range was zero to 15.0 percent. More than one in ten teens (10.9 percent) reported being the victim of sexual dating violence during the past year, and the range across schools was zero to 17.0 percent.

The purpose of this study was to examine how demographic characteristics such as sexual orientation, school characteristics such as the school poverty rate, and community characteristics such as the population density of the county relate to the possibility that a New Hampshire teen will be the victim of dating violence.

Demographic Risk Factors for Dating Violence Among Teens in New Hampshire

Being female, a racial/ethnic minority, or a sexual minority (including lesbian, gay, bisexual, or questioning) significantly increased the risk of being the victim of sexual and physical dating violence.

Racial minority teens in New Hampshire were more likely than white teens to report physical dating violence victimization (16.7 percent versus 9.7 percent) and more likely to report sexual dating violence victimization (14.4 percent versus 8.4 percent) during the past year.

Girls were more likely than boys to report physical dating violence victimization (11.0 percent versus 7.1 percent) and were more likely to report sexual dating violence victimization (15.7 percent versus 5.2 percent) during the past year.

Compared to heterosexual youth, sexual minority teens reported higher rates of physical dating violence victimization (24.7 percent versus 7.5 percent) and sexual dating violence victimization (26.1 percent versus 8.9 percent). Among sexual minority youth, questioning boys were the most likely to report being the victim of dating violence: 35.1 percent of boys who were unsure of their sexual orientation reported physical dating violence victimization and 32.9 percent reported sexual dating violence victimization.

The higher rates of dating violence victimization among racial and sexual minority teens can perhaps be explained by minority stress, caused, for example, by discrimination among racial minority youth and feelings of shame among sexual minority teens. Experiences of minority stress among sexual minority teens may contribute to the risk of dating violence victimization by increasing self-blame for the victimization, which in turn fuels a lack of self-efficacy to leave a relationship and a perception of a lack of alternatives to the current relationship.

School and Community Characteristics and Dating Violence

Teens who lived in more impoverished New Hampshire communities reported higher rates of physical dating violence than teens who lived in less-impoverished communities. Although we did not measure variables that may explain these relationships, we can draw on previous research for insight. First, high poverty in a community may increase stress among couples, and stress is tied to intimate partner violence (IPV). Further, high poverty rates may also be associated with distrust in and cynicism toward the justice system, feelings that may decrease the likelihood that victims will seek help for IPV (thus increasing the risk for re-victimization).4 In addition, living in a disadvantaged community may lead to weak ties between community residents, also referred to as low collective efficacy (that is, lack of social cohesion among community members). These weak ties can leave residents more vulnerable to violence within their relationship,5 as other residents are less likely to intervene on behalf of the victim and victims are less likely to seek help from neighbors6 or from more formal supports (such as police or shelters7).

The population density of the towns in which youth went to school was unrelated to both physical and sexual victimization. In other words, teens who lived in rural communities experienced dating violence victimization at rates similar to teens who lived in urban and suburban communities. This finding is consistent with other research which has found that overall rates of dating violence and IPV are similar across rural, urban, and suburban locales, although some types of IPV (for example, intimate partner homicide) are more common in rural compared to urban and suburban locales.8

Teens who reported participating in community groups (including sports groups and church groups) were more likely to report sexual dating violence victimization than teens who reported that they did not participate in community groups. This finding was unexpected, and it will be important for future research to replicate and better understand it.

Finally, teens who reported higher levels of community mattering reported lower levels of physical and sexual dating violence victimization. As Elliott et al. write, mattering is “the perception that, to some degree and in any of a variety of ways, we are a significant part of the world around us.”9 It is possible that in communities with higher levels of collective efficacy, teens may report higher levels of community mattering and thus lower rates of dating violence. Indeed, research has demonstrated that an environment characterized by a lack of academic support10 is related to a greater likelihood of physical dating violence, whereas general school support—the feeling that teachers and students care about them—is a protective factor for physical dating violence.11 Of note, teens in more impoverished New Hampshire communities reported lower feelings of mattering than did teens in less-impoverished communities.

Implications

Based on the findings presented in this brief and the broader research on dating violence among teens, we suggest the following:

Initiatives that focus on reducing poverty and improving teens’ experiences of community mattering could be important components of more comprehensive efforts to reduce the incidence and prevalence of dating violence in New Hampshire.

Initiatives that focus on reducing minority stress are a key component to effective dating violence prevention and presumably would reduce other health inequities (for example, poorer physical health status among minorities).

Dating violence is preventable. Several evidence-based programs (such as Green Dot, Safe Dates) have demonstrated reductions in dating violence.12

More research and community conversations are needed about how to ensure that all teens in New Hampshire have access to comprehensive violence prevention initiatives in all grade levels that include a focus on diversity and inclusivity, positive youth development (for example, the sense of mattering and purpose), and structural inequities (such as poverty).

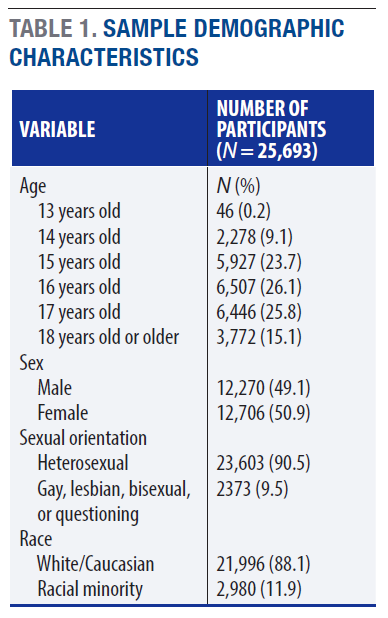

Data

This study included 24,976 high school students at least 13 years old who participated in the 2013 New Hampshire Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), reported dating histories (presented to youth as “dating or going out with”) during the 12 months prior to the survey, and had no missing data on variables used in all analyses (such as demographic variables or dating violence victimization). Although 38,181 high school students participated in the survey, only those who had dated were included in order to provide the most accurate estimates of dating violence (since students who had not dated would not have the opportunity to be exposed to dating violence). Also, teens 12 and younger were removed; a small portion of individuals were over the age of 18. See Table 1 for participant demographic characteristics. The YRBS is part of a multi-decade Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) project that monitors health risk behaviors (for more information, see http://education.nh.gov/instruction/school_health/hiv_data.htm). The data presented herein are derived from 71 New Hampshire public high schools (out of 83 in the state) that volunteered to administer the YRBS survey to all students in the school during the spring of 2013. Of the 71 schools participating, the YRBS response rate was 81 percent. Parental consent was obtained through local parental permission procedures. Students completed the self-administered questionnaire during one class period. The CDC’s Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Endnotes

1. L. Kann, S. Kinchen, and S.L. Shanklin, “Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2013,” MMWR Surveillance Summaries 63, Suppl. 4 (2014):1–168; V.L. Banyard and C. Cross, “Consequences of Teen Dating Violence: Understanding Intervening Variables in Ecological Context,” Violence Against Women 14, no. 9 (2008): 998–1013; J.G. Silverman et al., “Dating Violence Against Adolescent Girls and Associated Substance Use, Unheathly Weight Control, Sexual Risk Behavior, Pregnancy, and Suicidality,” Journal of the American Medical Association 286 (2001): 572–79.

2. C.M. Dardis et al., “An Examination of the Factors Related to Dating Violence Perpetration Among Young Men and Women and Associated Theoretical Explanations: A Review of the Literature,” Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 16 (2014): 136–52; K.J. Vagi et al., “Beyond Correlates: A Review of Risk and Protective Factors for Adolescent Dating Violence Perpetration,” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 42, no. 4 (2013): 633–49.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “The Social Egological Model: A Framework for Prevention” (Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2013).

4. G.M. Pinchevsky and E.M Wright, “The Impact of Neighborhoods on Intimate Partner Violence and Victimization,” Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 13, no. 2 (2012): 112–32; C.E. Ross and J. Mirowsky, “Neighborhood Disorder, Subjective Alienation, and Distress,” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 50, no. 1 (2009): 49–64; R.J. Sampson and D.J. Bartusch, “Legal Cynicism and (Subcultural?) Tolerance of Deviance: The Neighborhood Context of Racial Differences,” Law and Society Review (1998): 777–804; P.S. Plass, “African American Family Homicide: Patterns in Partner, Parent, and Child Victimization, 1985–1987,” Journal of Black Studies 23, no. 4 (1993): 515–38.

5. J.E. Stets, “Cohabiting and Marital Aggression: The Role of Social Isolation,” Journal of Marriage and Family 53 (1991): 669–80.

6. Pinchevsky and Wright, 2012; C.R. Browning, “The Span of Collective Efficacy: Extending Social Disorganization Theory to Partner Violence,” Journal of Marriage and Family 64, no. 4 (2002): 833–50; E.M. Wright and M.L. Benson, “Clarifying the Effects of Neighborhood Disadvantage and Collective Efficacy on Violence ‘Behind Closed Doors,’” Justice Quarterly 28, no. 5 (2011): 775–98.

7. Pinchevsky and Wright, 2012; Plass, 1993.

8. K.M. Edwards, “Intimate Partner Violence and the Rural–Urban–Suburban Divide: Myth or Reality? A Critical Review of the Literature,” Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 16, no. 3 (2015): 359–73.

9. G.C. Elliott et al., “Perceived Mattering to the Family and Physical Violence Within the Family by Adolescents,” Journal of Family Issues 32, no. 8 (2011): 1007–29.

10. E. Reed et al., “Social and Environmental Contexts of Adolescent and Young Adult Male Perpetrators of Intimate Partner Violence: A Qualitative Study,” American Journal of Men’s Health 2, no. 3 (2008): 260–71.

11. H. Champion et al., “Contextual Factors and Health Risk Behaviors Associated With Date Fighting Among High School Students,” Women & Health 47, no. 3 (2008): 1–22.

12. E.I. Capilouto et al., “’Green Dot’ Effective at Reducing Sexual Violence,” 2014, works.bepress.com/anncoker/100/ V.A. Foshee et al., “The Safe Dates Program: 1-Year Follow-Up Results,” American Journal of Public Health 90, no. 10 (2000): 1619–22.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jeffrey Metzger and the New Hampshire Department of Education for providing them with the New Hampshire YRBS data. The authors would also like to thank Kara Anne Rodenhizer for her assistance with collection of community-level data and Dr. Hong Chang for his assistance with analyses. Thanks to Michael Ettlinger, Michele Dillon, Curt Grimm, Amy Sterndale, Laurel Lloyd, and Bianca Nicolosi at the Carsey School of Public Policy and Patrick Watson for editorial contributions.