download the brief

Key Findings

Young adult parents (age 18–24) are disproportionately poor compared to both other young adults and older parents. More than nine in ten of these poor young parents report participating in a safety net program.

The EITC has a wide reach: an estimated two- thirds of poor young parents receive the credit.

Programs with high participation rates and relatively large benefit dollars—like the EITC—are especially effective at reducing young-parent poverty; poverty for this group would increase by 6.7 percentage points absent the EITC.

This brief was drafted over the course of many months preceding the COVID-19 pandemic. But given the effects of this crisis on unemployment, it is worth noting that the utility of social safety net programs linked to work—namely the Earned Income Tax Credit, here—may be affected. In particular, 10 percent of poor young adult parents work in retail-related industries, and 16 percent are in key service industries and many more will be affected.1 These industries are hard hit by the pandemic, and lost earnings will affect these parents’ credit values under current EITC structure.

While these shifts don’t alter the results presented here, the finding that the EITC is especially successful in reducing poverty among young adult parents suggests the necessity of protecting these credits through policy. Possible strategies might include allowing filers to report prior year earnings, counting unemployment benefits as income, or extending the credit to family caregivers even if they have no earned income).2 Reliance on the EITC is near universal among poor young adult parents, and those dollars go far in protecting these families and their children. However, moving forward, lost earnings are likely to push EITC rates lower and participation rates of other safety net programs less linked to work, like WIC, higher.

An estimated 2.5 million very young children live with a young adult parent (age 18 to 24), with low-income children especially likely to do so.3 As young parents navigate educational, career, and family trajectories, certain safety net programs are especially useful at lifting their families from poverty. More than four in five young adult parents,4 regardless of income, participate in at least one major safety net program.

The most widely used of these programs, and the most effective at reducing poverty, is the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC).5 Continued efforts to expand and support access to the EITC can provide young families with a key source of poverty-alleviating income.

Earned Income Tax Credit Reaches Nearly Two-Thirds of Poor Young Parents

Of the safety net programs examined in this brief—the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); the EITC; the Special Nutrition Assistance Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); energy assistance; free or reduced-price school lunch; and housing subsidies—84 percent of young adult parents report participating in at least one. Because some of these programs, particularly the EITC, are available to those above the poverty line, receipt is high generally, although young parents do have higher poverty rates than other young adults or other parents (25.6 percent versus 19.7 and 11.6 percent, respectively).

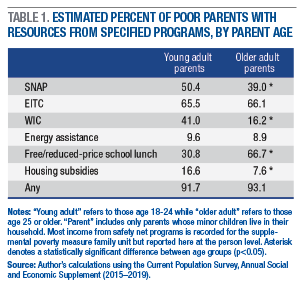

Among young parents with resources less than the poverty line, participation in at least one program is nearly universal (Table 1), with almost two-thirds—the highest share—reporting EITC receipt. Receipt of WIC is also high among this group, perhaps not surprising given the eligibility criteria (the program is limited to pregnant women and children under age 5) and the tendency for younger parents to have younger children. In contrast, older adult parents, whose children are more likely to be school-aged than those of young adults, more often report use of free and reduced-price school lunch. Differences between the two groups in receipt of SNAP benefits and housing subsidies may be driven by other age-linked family characteristics: poor young parents are more likely to meet the criteria for official poverty,6 and thus be income-eligible for SNAP, and they are more likely to be renters, and thus able to utilize housing vouchers.

EITC and SNAP Especially Impactful for Reducing Poverty Among Young Adult Parents

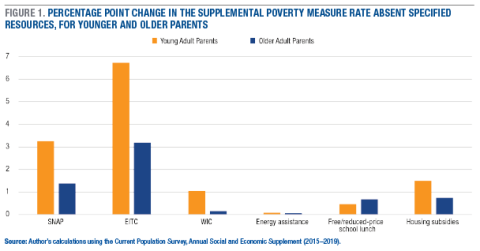

Along with differences in program receipt, there are substantial differences in the role that specific programs play in reducing poverty rates among young adult parents. For instance, a much smaller share of young adult parents receives housing subsidies than receives WIC, but, because their average housing subsidy value is nearly four times that of their average WIC income, the poverty rate among young parents would be 1.5 percentage points higher without housing subsidies and just 1.0 percentage point higher without WIC (Figure 1).7 In other cases, wide receipt and high values work together for an enhanced poverty reduction effect, as in the case of the EITC; without this credit, young parents’ poverty rate would rise by 6.7 percentage points.

Also important are the differences across parental age in poverty reduction. While similar shares of poor younger and older parents receive the EITC, Figure 1 suggests the credit goes more than twice as far in reducing poverty among young adults than among their older counterparts (likely in part because poverty rates are much lower among older parents to begin with). In contrast, although young adult parents more often receive heating subsidies, the poverty-alleviating effects are minimal and similar across age groups, both because low shares of parents report receipt and because subsidy values are relatively low.

Policy Implications

Although the Earned Income Tax Credit is an effective poverty-alleviating tool for many populations, including young adult parents, one-fifth of eligible families do not claim it.8 Those who do not may be unaware of it—and its refundable nature—particularly if they do not have a federal tax liability. In addition, because of age restrictions on the credit for filers without children in the home, nonresident young adult parents do not benefit from the credit in the same way as other young parents. The EITC also does not support families who are unable to work.

The measures used in this brief reflect only the role of the federal EITC and do not capture the role that state-level credits, particularly those that are refundable, may play in boosting family income. Earlier work shows that most states with the highest shares of families headed by young adults do not offer a state credit.9 Given strong evidence that the credit is widely accessible and supports family well-being,10 and that credits can be delivered through existing tax infrastructure, EITC outreach and expansion is a valuable tool for reducing poverty among and beyond young adult parents and their families.

However, the EITC isn’t the only important policy mechanism for reducing poverty among young adult families. SNAP is also effective, and, unlike the EITC, it provides a monthly benefit that can help smooth income fluctuations within the year11 for families who become and remain enrolled in SNAP. For the relatively few young adult families that receive housing subsidies, the vouchers go much further in reducing poverty than other programs with higher participation but lower dollar values. Existing research shows the importance of housing vouchers on a variety of family outcomes, including children’s education.12 According to the Urban Institute, however, just 20 percent of eligible households receive housing vouchers, a share that has shrunk over time.13 Not only are resources for housing vouchers extremely limited, but local housing authorities have considerable ability to establish priorities for some groups over others (for example, seniors, working families). Ensuring that young adults and their young families are among these priority groups could provide stability and support at a key time for both parents and children alike.

Data and Methods

The data in this brief are drawn from five years (2015–2019) of the Annual Social and Economic Supplement of the Current Population Survey (CPS). This brief relies on the supplemental poverty measure (SPM), which considers a family’s resources including post-tax income and transfers, government assistance, and deductions for medical and work expenses, including transportation and child care. SPM thresholds account for consumer spending patterns on food, clothing, shelter, and utilities, and they are adjusted geographically to account for differences in the cost of housing. Readers should be cautious when comparing estimates between groups because the CPS is asked of a sample of the population rather than the total population. Although some estimates may appear different from one another, it is possible that any difference is due to sampling error. Further, in some cases very small differences may be statistically significant due to the large sample size of the CPS. All differences discussed in this brief are statistically significant (p<0.05).

Endnotes

1. Author’s analysis. Retail-related industries include people employed in all “retail trade” industries, and service industries include those in arts, entertainment, recreation, accommodation, food service, and other services except public administration (see https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/methodology/Industry%20Codes.pdf). These percentages are as a share of all poor young adult parents;

shares among only those who are employed are higher.

2. These and other policy solutions are being considered in different forms, often drawing from earlier proposed adjustments to the credit. See, for example, Elaine Maag,“Expanding the EITC to Include Family Caregivers” (Washington, DC: Urban Institute & Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center, 2020), https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxvox/expanding-eitc-include-family-caregivers.

3. Jessica Carson, “For One in Four Very Young, Low-Income Children, Parents Are Young Too” (Durham, NH: Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire, 2019), https://carsey.unh.edu/publication/young-adult-families.

4. In this brief, “parent” refers to residential parents of minors. Those who only have children over age 18 in the household or who have minor children living elsewhere

are excluded.

5. Though a detailed account is beyond the scope of the current analysis, additional young families are lifted closer to the poverty line, and out of deep poverty, by social safety net programs.

6. This brief uses the supplemental poverty measure, which differs from the official measure used to determine eligibility for safety net programs. Of the parents in Table 1, 80 percent of young adults are also poor under the official poverty measure, as are 68 percent of older adults.

7. It is important to note that the accessibility of these programs is not uniform; for example, housing subsidies can be especially difficult to access. Recent estimates (2016) by the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) found a median wait time of 1.5 years for a Housing Choice Voucher, with one-quarter of wait lists reaching at least three years. See “Closed Waiting Lists and Long Waits Await Those Seeking Affordable Housing, According to New NLIHC Survey” (Washington, DC: NLIHC, 2016), https://nlihc.org/news/closed-waiting-lists-and-long-waits-await-those-seeking-affordable-housing-according-new-nlihc.

8. Internal Revenue Service, “EITC Participation Rates by States,” https://www.eitc.irs.gov/eitc-central/participation-rate/eitc-participation-rate-by-states.

9. Carson, 2019.

10. Tax Policy Center, “Briefing Book: A Citizen’s Guide to the Fascinating (Though Often Complex) Elements of the U.S. Tax System,” https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/how-does-earned-income-tax-credit-affect-poor-families.

11. James P. Ziliak, “Modernizing SNAP Benefits,” Policy Proposal 2016-06 (Washington, DC: Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution, 2016), https://www.hamiltonproject.org/assets/files/ziliak_modernizing_snap_benefits.pdf; Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), “Chart Book: SNAP Helps Struggling Families Put Food on the Table” (Washington, DC: CBPP, 2019), https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/chart-book-snap-helps-struggling-families-put-food-on-the-table.

12. Corianne Payton Scally, Samantha Batko, Susan J. Popkin, and Nicole DuBois, “The Case for More, Not Less: Shortfalls in Federal Housing Assistance and Gaps in Evidence for Proposed Policy Changes” (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, 2018), https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/95616/case_for_more_not_less.pdf.

13. Scally et al., 2018.

About the Author

Jess Carson is a research assistant professor with the Vulnerable Families Research Program at the Carsey School of Public Policy. Since joining Carsey in 2010, she has studied poverty, work, and the social safety net, including policies and programs that support low-income workers like affordable health insurance, food assistance programs, and quality child care.

Acknowledgments

This brief was made possible with support from the Annie E. Casey Foundation. The author thanks Michael Ettlinger and Sarah Boege of the Carsey School of Public Policy as well as Beth Mattingly, a Carsey fellow and an assistant vice president in the Regional and Community Outreach Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, for their feedback on an earlier draft; Laurel Lloyd and Nick Gosling for their support in preparing the brief for publication; and Patrick Watson for his editorial assistance.