download the brief

Key Findings

While fewer than 5 percent of children live with young adult parents (age 18–24), the share among children age 0–3 is 16 percent, and among low-income children that age, it is 25 percent.

Low-income young adult parents have different characteristics than their older counterparts; for example, they are more often parenting their first child with no co-parent present, and they have higher rates of school enrollment.

Policies that support families headed by young adults should engage “whole family” approaches, for example, connecting the youngest children with quality care while preparing their parents for successful careers.

An estimated 2.5 million children under age 4 are being raised by parents age 18–24, with significant concentrations of these families in the South and Southwest. Compared with older parents, these young adult parents are more often raising their first child, enrolled in school, and parenting without a residential co-parent.

These characteristics can add up to a lack of resources for children in families headed by young adults during a key period of child development, and they present an imposing set of barriers for young parents who are in a critical period for shaping their own educational and employment trajectories. While supportive policies exist, most could be strengthened to better support young adult families through stronger income supports such as refundable tax credits, more affordable education for parents via mechanisms like Pell grants, and stronger child care systems.

This brief maps the distribution of children living with young adult parents, describes their parents’ characteristics, and details ways to strengthen policy supports that can fortify their families’ ability to succeed.

Geographic Distribution of Very Young Children With Young Adult Parents Is Uneven

It is to be expected that the children of young adults are more likely to still be young, and indeed 16.2 percent of children age 0–3 live in young-adult-headed families, compared with 1.3 percent of children age 4–17. However, the geographic distribution of very young children in these families is uneven across the nation: the share of children age 0–3 living with young adult parents is much higher in the South-Southwest (Map 1). In New Mexico and Arkansas, more than 25 percent of very young children are parented by young adults. Across the Northeast, rates are uniformly low, for example, with estimated rates below 10 percent in Massachusetts and New Jersey.

One-in-Four Low-Income Children Age 0–3 Live With a Young Adult Parent

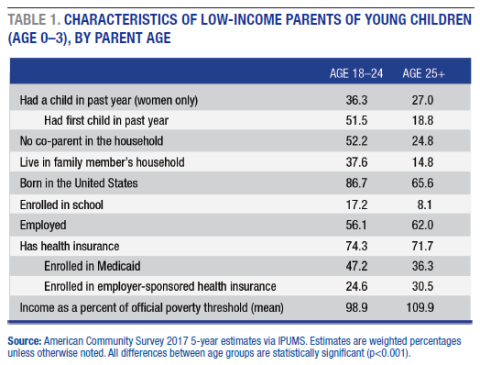

Among children with incomes below twice the poverty line (“low-income”), living with young adult parents is even more common; nationwide, one-in-four low-income children age 0–3 have young adult parents. Table 1 shows that the parents of these very young low-income children face a set of challenges: they are less likely to be working and are more often in school compared with similarly low-income older parents. In addition, low-income young adult mothers are more often new to parenthood and are raising a family without a residential co-parent, a situation that limits an important possibility for financial support. However, it is worth noting that social support may be stronger among young adult parents in some ways, as they more often live with other family members and are more likely than older parents to have been born in the United States.

Policy Implications

Importantly, young adult parents are less likely to have a co-parent in the house, more likely to be enrolled in school, and less likely to be working than are older parents. Paired with the demands of their especially young children, accessing good, affordable child care is a pressing concern for this group. In a key life-course period for entering the labor market and establishing a career, the lack of child care can have serious long-term effects. And as income is linked with age more generally, young adults are more likely to need broader income supports than older populations might, especially when paired with the pressures of new parenthood. These families would benefit not only from income to help them make ends meet, but also through mechanisms that support college affordability and shape their earnings potential. The following are specific policy mechanisms to address these needs.

Access to high-quality child care: Ensuring access to high-quality child care is critical both as a work support for young parents and for the developmental trajectories of their young children. Too often, however, high-quality child care is either unavailable or unaffordable. Steps have been taken to increase child care quality more broadly, but access to this care is stratified, and the highest-quality care is often the costliest (even leaving aside the issues of uneven geographic distribution and long waiting lists for enrollment). Child care subsidies are one way to address affordability, although families’ ability to access and use these subsidies is not guaranteed. First, the demand for child care assistance significantly outstrips available funds. In 2016, twenty states either had a wait list or had frozen intake (wherein demand was so high that states no longer accepted applications) for child care assistance. As a result, uptake among eligible families is very low overall. Second, the value of child care subsidies—the child care subsidy “reimbursement rate”—varies significantly between states. In many states, rates are so low that child care providers would lose money by accepting subsidies, and as such, they elect not to, meaning that even receiving a subsidy doesn’t guarantee child care access. For very young low income children, Early Head Start can be an alternative to state subsidized child care, but the program is significantly underfunded, and only 7 percent of eligible children have access to the program. Taken together, significant underfunding of child care subsidies and programs, a lack of child care slots, and an underpaid child care workforce function to limit access to and affordability of care for many families; for families with fewer resources, this can preclude the ability to build educational and employment trajectories altogether.

Child and Dependent Care Credit: The Child and Dependent Care Credit helps to defray the cost that families pay for child care while working. The credit is not presently refundable, so even though it is worth 20–35 percent of dependent care expenses paid, a family with no federal personal income tax liability is not eligible for any credit. A report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine exploring child poverty recommended that the credit be made refundable, a move that would increase earnings by around $9 billion and cost $5.1 billion to implement. Given the challenges facing the child care subsidy system (above), tax credits might offer relief to young adult families who are not served by child care subsidies, in the absence of subsidy reform.

Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC): The EITC is consistently identified as one of the nation’s most important poverty-reducing programs for children. And while four of five eligible filers claim the EITC, both access to and the value of this credit could be further bolstered. For instance, filers without a resident child must be 25 to claim the credit; lowering this age requirement could allow more nonresidential parents to claim the credit and support their children. Given the significant share of low income, young adult parents raising children alone, this change could substantially benefit young-adult families. Further, state-level EITCs expand upon the federal benefit in important ways, but six of the nine states with the highest shares of young adult families don’t offer a state credit, and in only two of the three states that do are the credits refundable (New Mexico and Louisiana).

College affordability: One of the most important mechanisms governing access to higher education is the Higher Education Act, last reauthorized in 2008. The act, which includes oversight for federal programs including student loans and college accreditation processes, was set to expire in 2013 but has been extended while lawmakers work on a full reauthorization. Such a reauthorization, called the College Affordability Act, was proposed in October 2019 and includes several elements relevant to families headed by young adult parents, including increasing the value of Pell grants, a key mechanism for expanding college access among lower-income populations but that has not kept pace with inflation. A reauthorization could also include better supports for college persistence and completion—also especially relevant for low-income young adult families who have competing demands on their time. Finally, beyond reauthorizing the act, 2020 presidential candidates have proposed a host of revisions to higher education, ranging from tuition-free college to revised income-driven student loan repayment plans. Supports that ease the costs of higher education and assist young adults in completing credentials that translate to higher-paying work can coalesce to raise income and enhance stability for young adult families and their children.

Data

The data for this brief are from the 2017 American Community Survey (ACS) five-year file, downloaded from IPUMS. Readers should be cautious when comparing estimates between groups because the ACS is asked of a sample of the population, rather than the total population. Although some estimates may appear different from one another, it is possible that any difference is due to sampling error. Further, in some cases very small differences may be statistically significant due to the large sample size of the ACS. Nonetheless, all differences discussed in this brief are statistically significant (p<0.05).

Endnotes

1. FPG Child Development Center, “The Children of the Cost, Quality, and Outcomes Study Go To School” (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina, 1999), https://fpg.unc.edu/sites/fpg.unc.edu/files/resources/reports-and-policy-briefs/NCEDL_CQO_technical_report.pdf.

2. National Center on Subsidy Innovation and Accountability “Waitlists” (Washington, DC: Early Childhood National Centers, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2017) https://childcareta.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/public/wait_list_vs_enrollment_freeze.pdf.

3. Uptake rates among eligible families are estimated at between 7 and 34 percent, depending on the study. See Nicole Forry, Paula Daneri, and Grace Howarth, “Child Care Subsidy Literature Review,” OPRE Brief 2013-60 (Washington DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013) https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/subsidy_literature_review.pdf.

4. Julia B. Isaacs, Erica Greenberg, and Teresa Derrick-Mills, “Subsidy Policies and the Quality of Child Care Centers Serving Subsidized Children” (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, 2018), https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/96361/subsidy_policies_and_the_quality_of_child_care_centers_serving_subsidized_children_2.pdf.

5. Research conducted by the Urban Institute in five counties across the nation suggests that, while between 80 and 90 percent of providers said they would accept vouchers, only 50–60 percent were serving or had recently served at least one vouchered family, and between 40 and 50 percent of providers said they would limit the number of enrollments from vouchered families. See Monica Rohacek and Gina Adams, “Providers in the Child Care Subsidy System: Insights into Factors Shaping Participation, Financial Well-Being, and Quality,” Research Report (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, 2017), https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/95221/providers-and-subsidies.pdf.

6. “Access to Head Start in the United States of America” (Washington, DC: National Head Start Association, 2019), https://www.nhsa.org/national-head-start-fact-sheets.

7. National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, “A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty, Consensus Study Report” (Washington DC: National Academies, 2019), https://www.nap.edu/read/25246/chapter/8#177.

8. Liana Fox, “The Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2018,” Report No. P60-268 (Suitland, MD: U.S. Census Bureau, 2019), https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2019/demo/p60-268.html.

9. Internal Revenue Service, “EITC Fast Facts,” https://www.eitc.irs.gov/partner-toolkit/basic-marketing-communication-materials/eitc-fast-facts/eitc-fast-facts.

10. Erica Williams and Samantha Waxman, “States Can Adopt or Expand Earned Income Tax Credits to Build a Stronger Future Economy” (Washington DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2019), https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/states-can-adopt-or-expand-earned-income-tax-credits-to-build-a.

11. American Council on Education, “Higher Education Act and Department of Education,” https://www.acenet.edu/Policy-Advocacy/Pages/HEA-DOE/Higher-Education-Act.aspx.

12. Megan Walter, “Analyzing the College Affordability Act: Changes to Pell and Other Grants” (Washington DC: National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators, 2019), https://www.nasfaa.org/news-item/19785/Analyzing_the_College_Affordability_Act_Changes_to_Pell_and_Other_Grants.

13. Spiros Protopsaltis and Sharon Parrott, “Pell Grants—A Key Tool for Expanding College Access and Economic Opportunity—Need Strengthening, Not Cuts (Washington DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2017), https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/pell-grants-a-key-tool-for-expanding-college-access-and-economic-opportunity.

14. Andrew Kreighbaum, “Letter Calls on Congress to Tie Pell Grant to Inflation,” Inside Higher Ed, July 25, 2017, https://www.insidehighered.com/quicktakes/2017/07/25/letter-calls-congress-tie-pell-grant-inflation; see letter linked within.

15. Adam Harris, “The College-Affordability Crisis Is Uniting the 2020 Democratic Candidates,” The Atlantic, February 26, 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2019/02/2020-democrats-free-college/583585/.

16. Steven Ruggles, Sarah Flood, Ronald Goeken, Josiah Grover, Erin Meyer, Jose Pacas, and Matthew Sobek, IPUMS USA: Version 9.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2019, https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V9.0.

About the Author

Jess Carson is a research assistant professor with the Vulnerable Families Research Program at the Carsey School of Public Policy. Since joining Carsey in 2010, she has studied poverty, work, and the social safety net, including policies and programs that support low-income workers like affordable health insurance, food assistance programs, and quality child care.

Acknowledgments

This brief was made possible through a grant from the Annie E. Casey Foundation. The author thanks Michael Ettlinger and Michele Dillon at the Carsey School of Public Policy, and Beth Mattingly, a Carsey Policy Fellow and an assistant vice president in the Regional and Community Outreach Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, for feedback on an earlier draft; Laurel Lloyd and Nicholas Gosling at the Carsey School for assistance with layout; and Patrick Watson for his editorial assistance.