download the brief

Key Findings

The older age structure of rural America increases its vulnerability to the coronavirus.

Though rural exposure to the virus was limited early in the pandemic, it is now spreading rapidly there.

Rural America’s older age structure increases expected mortality rates there, but other factors also influence its vulnerability to the virus.

(Revised May 13, 2020) As the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic spreads, attention has focused on urban America1 where the bulk of the cases and deaths have occurred. Rural America is at considerable risk as well. Though the incidence of the virus in nonmetropolitan America is currently modest, it is spreading rapidly with significant implications for future mortality.2

The mortality a community suffers from exposure to the coronavirus is influenced by social and demographic characteristics including: health, inequality, poverty, food insecurity, race/Hispanic origin, and access to health care. The age structure of the population also has a substantial impact on the severity and mortality associated with the coronavirus. Although mortality rates associated with a given age vary among studies, age-specific mortality rates are consistently very low for younger age cohorts and much higher for the oldest cohorts.3 Thus, areas with older populations have considerably higher death rates among those exposed to the coronavirus than areas with younger populations. Certainly, the risk factors noted above also exert an influence, but the age structure is a powerful driver of the local coronavirus death rate. This brief focuses on estimating the influence that the local age structure has on coronavirus death rates among those exposed to it in rural and urban counties in the United States.4

The Spread of the Virus to Rural Areas with Older Populations Has Implications for Mortality Rates

A major reason the rural population may be more vulnerable to the virus is that it is considerably older than the urban population. More than 26 percent of the nonmetropolitan population is 60 or older compared to 21 percent of the metropolitan population. Mortality and the severity of the virus are both significantly higher among older adults. Some 55 percent of nonmetropolitan counties have estimated mortality rates among those infected that are significantly higher than the United States as a whole compared to 22 percent of metropolitan counties.

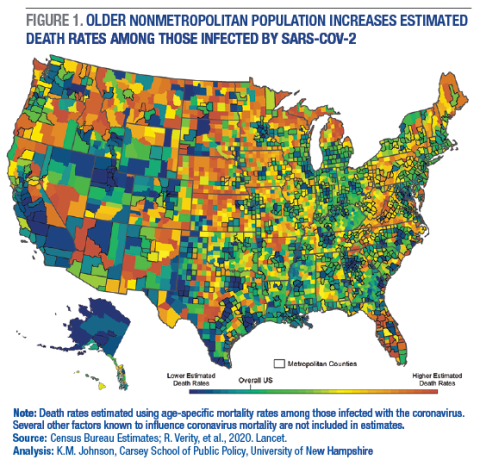

Estimated population mortality rates among those infected are higher in large regions of rural America where the population is older (Figure 1). This includes much of the Great Plains, Upper Great Lakes, Northern New England, and Appalachians as well as in northern areas of the West. In contrast, the younger population in many metropolitan areas (outlined in black) reduces the potential risk of mortality from infection.

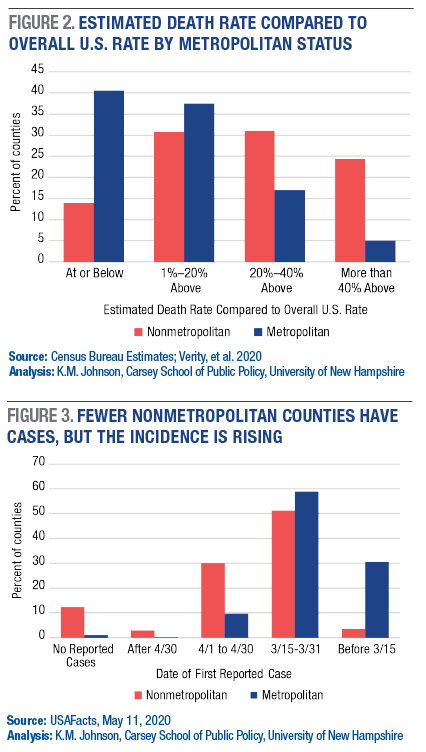

Nearly 41 percent of metropolitan counties have estimated death rates at or below that for the United States a whole compared to just 14 percent of nonmetropolitan counties (Figure 2). In contrast, 24 percent of the rural counties have mortality rates that are at least 40 percent above those for the United States compared to 5 percent of the metropolitan counties. Among rural counties that are not adjacent to metropolitan areas, 38 percent have estimated death rates in this highest category compared to just 3 percent of counties in metropolitan areas of more than one million.

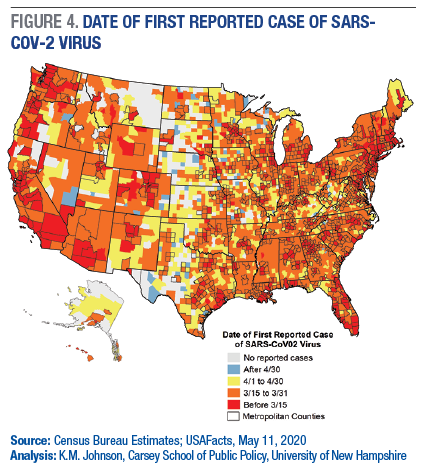

Both the incidence of the coronavirus and resulting deaths are far greater in metropolitan areas. Metropolitan areas contain 86 percent of the U.S. population. Yet, more than 93 percent of the cases and 95 percent of the deaths from the coronavirus to date have been urban. The virus also appeared earlier in metropolitan areas (Figure 3). It was first identified by March 15th in 31 percent of the urban cases compared to just 4 percent of the rural counties.5 By March 31st, 90 percent of the urban counties had cases of the virus, but just 55 percent of the rural counties. And, though 12 percent of nonmetropolitan counties have yet to experience a reported case, this number is dwindling. More than 33 percent of rural counties experienced their first case of the virus since April 1st compared to less than 10 percent of urban counties.

The spatial progression of the virus is reflected in its initial concentration in metropolitan areas. Nearly 31 percent of all metropolitan counties, outlined in black in Figure 4, already had cases of it by March 15th, as shown in red. Later, the virus spread to the remaining urban counties and to many nonmetropolitan counties near metropolitan areas, shown in orange. Since April 1st, more rural counties have experienced their first case of the virus as reflected in yellow and blue. Rural areas that have yet to experience the virus are concentrated in the western Great Plains and in scattered areas far from metropolitan centers. However, many of these counties are estimated to have high mortality rates when the virus arrives. In all, more than 65 percent of the 254 counties that have yet to experience a case of the virus have estimated mortality rates at least 40 percent above those of the United States as a whole based on age.

Age Is Important, but So Are Other Factors

Though age has a substantial influence on the likelihood of mortality from exposure to the virus, it is not the only important factor. Rural populations have higher incidences of chronic health conditions (heart, lung, and diabetes), higher obesity rates, and greater food insecurity, all of which makes them more vulnerable to contracting the illness and suffering serious or even fatal effects. Access to health care is also important to the treatment of serious cases of the virus, yet there are fewer physicians, health care workers, and hospitals in rural areas. Some rural hospitals have closed in the past few years and many more are struggling to stay open often by cutting services and staff. Timely access to major hospitals and specialists is imperative for those with severe virus symptoms. Yet, while 14 percent of the U.S. population resides in nonmetropolitan counties, less than 10 percent of the ICU beds are there. Nearly 50 percent of U.S. counties have no ICU beds at all, and most of these are rural counties.6 Even the lower population density in rural America that some suggest may diminish the incidence of the virus is a double-edged sword. The rural population is spread across 72 percent of the land area of the country. This makes it easier to maintain social distance, but it means that the specialized care only available at comprehensive medical centers is far away from many rural residents.

The Virus Response Must Consider Rural As Well As Urban America

A substantial majority of coronavirus cases and deaths will occur in metropolitan areas where 86 percent of the population resides, even though rural death rates are higher. But, the number of rural cases and deaths is now rising and will have a significant impact on rural people, places, and institutions. Rural America is a deceptively simple term for a remarkably diverse collection of places.7 It faces unique demographic, social, and institutional challenges in facing the onslaught of the coronavirus. Distances are greater and places are more isolated. The lower population density in rural America has likely contributed to the lower incidence of the coronavirus there so far. But the situation is changing rapidly. As the virus spreads, the risk to rural areas grows because of its population characteristics and limited access to medical resources. Any virus related changes that disrupt the infrastructure and supply chains of rural America have significant implications for the nation at large because it provides most of the country’s food and raw materials. The fates of rural and urban America are inextricably intertwined, so responding to the virus must address the needs of rural as well as urban America.

Methods

This brief focuses on how the age structure influences the relative death rates in rural and urban areas, not on the absolute number of deaths or the overall mortality rate, which will be influenced by many other factors. I estimated death rates among those infected with the virus for each county using age-specific mortality estimate from new research on the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in China.8 In the China research, estimated mortality rates were adjusted to reflect the population age structure and the likely differential underreporting of cases by age. Consistent with previous research, they found mortality rates were far higher for older adults. I applied these mortality rates to the age structure of the overall U.S. population and to that of each U.S. county using recent age estimates from the U.S. Bureau of the Census. The estimated mortality rate for the United States as a whole was 9.2 deaths per 1,000 infected individuals. Rather than use absolute death rates, which are sensitive to many conditions specific to a given country, I calculated a ratio comparing the death rate of each county to that for the nation as a whole. These death rates are relative rather than absolute. Unless the basic assumption of the model that age specific death rates rise substantially with age is incorrect, the positions of the counties relative to one another should be largely invariant. Note that the potential mortality rate is per 1,000 infected individuals. Thus, the mortality rate estimates are not influenced by the proportion of a county population that is infected. So, a county with a higher estimated mortality rate but a lower proportion of infected individuals may have fewer deaths than a county of the same size with a lower mortality rate but a larger proportion of its population infected.

Endnotes

1. The terms nonmetropolitan and rural are used inter-changeably, as are the terms urban and metropolitan.

2. T. Marema and T. Murphy, “Covid-19 Update: April Saw Rural America’s Infection Rate Increase 8-Fold,” Daily Yonder, May 4, 2020. https://www.dailyyonder.com/covid-19-update-april-saw-rural-americas-infection-rate-increase-8-fold/2020/05/04/

3. R. Verity, et al., “Estimates of the Severity of the Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Model-based Analysis,” The Lancet Infectious Diseases, March 30, 2020. https://www.thelancet.com/action/showPdf?pii=S1473-3099%2820%2930243-7

4. While I recognize that numerous other factors in addition to the age structure will influence the incidence and number of deaths from the coronavirus in a given area, I do not address them here. My concern is with how differences in the age structure in rural and urban areas are likely to impact the death rates from the virus.

5. Data on number of cases and deaths by county come from the USAFacts Project. https://usafacts.org/visualizations/coronavirus-covid-19-spread-map/

6. M.A. Williams, B. Gelaye. and E.M.B. Leib, “The Covid-19 Crisis is Going to Get Much Worse when It Hits Rural Areas,” Washington Post, April 6, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/04/06/covid-19-crisis-is-going-get-much-worse-when-it-hits-rural-areas/

7. K.M. Johnson, “Where Is Rural America, and What Does It Look like,” The Conversation, February 20, 2017. https://theconversation.com/where-is-rural-america-and-what-does-it-look-like-72045

8. R. Verity, et al., 2020.

About the Author

Kenneth M. Johnson is Senior Demographer at the Carsey School of Public Policy, Professor of Sociology at the University of New Hampshire, and an Andrew Carnegie Fellow.

Acknowledgments

Barbara Cook provided GIS support for this project, and Semra Aytar provided epidemiological analysis. This research was supported by the author’s Andrew Carnegie Fellowship and the New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station in support of Hatch Multi-State Regional Project W-4001 through joint funding of the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, USDA. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and it does not necessarily represent the official views of the sponsoring organizations.