download the brief

Key Findings

In December 2024, 61 percent of New Hampshire workers had paid medical leave, 38 percent had paid parental leave, and 28 percent had paid family medical leave benefits.

About 3 percent of New Hampshire workers were enrolled in the NH Voluntary Paid Family and Medical Leave (PFML) program by June 2025. The NH PFML program did little at the state level to increase overall paid family and medical leave benefits and maintained existing inequities in coverage.

Fewer than one in five New Hampshire workers had heard of the NH PFML Program between 2022 and 2024.

Introduction

Twenty-five years of research establishes the numerous health and economic benefits of paid family and medical leave for families, children, and businesses.1 Despite the overwhelming evidence of these benefits, the United States lacks a federal paid family and medical leave policy. In 1993, the United States passed the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) which provides 12 weeks of job-protected, unpaid leave to workers in firms with 50 or more employees who have worked 1,250 hours in the previous year for the same employer for qualifying medical, family, and parental leave reasons. These eligibility criteria translate in to more than 60 percent of New Hampshire workers lacking access under the FMLA,2 primarily due to the large share of small firm employees in our state.3

In the absence of national policy, states operate as laboratories of innovation. Fourteen states4 have enacted comprehensive, universal, state-run programs that provide varying levels of paid family and medical leave, which allow workers to take an extended number of weeks away from their jobs, with some wage replacement, to care for a seriously ill, injured, or disabled family member, a new child, or to tend to one’s own serious health condition. In states without comprehensive paid leave programs, workers’ access to paid leave depends on whether one’s employer includes it as a workplace benefit. The result is vastly uneven access, with women, workers with low education or low pay, and those working in small firms typically lacking access.

Two alternative voluntary paid family and medical leave approaches were implemented in 2023. The first is a private-public partnership delivery system and the second is for state legislatures to grant private insurance companies the authorization to sell paid family leave insurance products in the state.5 Neither of these voluntary approaches guarantee paid leave to private-sector workers, and both appear to have limited reach in terms of increasing paid family and medical leave benefits.

The first approach, as exemplified in New Hampshire, is a state partnership with a private insurance company to offer paid family and medical leave to employers or individuals without paid leave who opt in to the program and pay a premium, essentially operating as a for-profit paid family leave insurance marketplace. Permanent state employees are automatically enrolled and diversify the risk pool. Vermont adopted a similar system, administered by the Hartford Insurance Group.

In New Hampshire, the state contracted with MetLife, one of the nation’s largest insurers, to offer paid family and medical leave. The statute creating the program specified that the policy sold must offer a minimum of six weeks of leave at 60 percent wage replacement. In the individual plan, there is a 7-month waiting period (but not for state or employer-sponsored workers) before a claim can be submitted. Job protection follows the FMLA requirements for the size of employer, length of time, and number of hours an employee must work to receive a guarantee of reinstatement to their job.6 Individual enrollment occurs within a 60-day period in December and January of each year, and individual premiums are capped at $5 per week. Employers may enroll at any time, can fully fund, split, or pass the cost onto their workers, and are eligible for a business enterprise tax (BET) credit of up to 50 percent of the premium they pay on behalf of their workers.

Understanding whether New Hampshire’s paid family and medical leave program increased coverage is important for policymakers and stakeholders, when considering paid leave policies. Ferreting out potential barriers to program enrollment, including lack of program knowledge, a limited six weeks of leave, and limiting wage reimbursement to 60 percent, will provide policymakers with considerations for program improvement.

Box 1. NH PFML Program’s Plan Types

The program has three plan types:

- state plan: full-time state employees are automatically enrolled

- employer group plan: employers opt in to the plan and purchase the product for their workers (premium paid by employer only, employee only, or a combination of both)

- individual plan: individual workers can opt in to the program if their employer does not offer paid leave and the worker pays the premium

New Hampshire Workers Lack Paid Family and Medical Leave Benefits

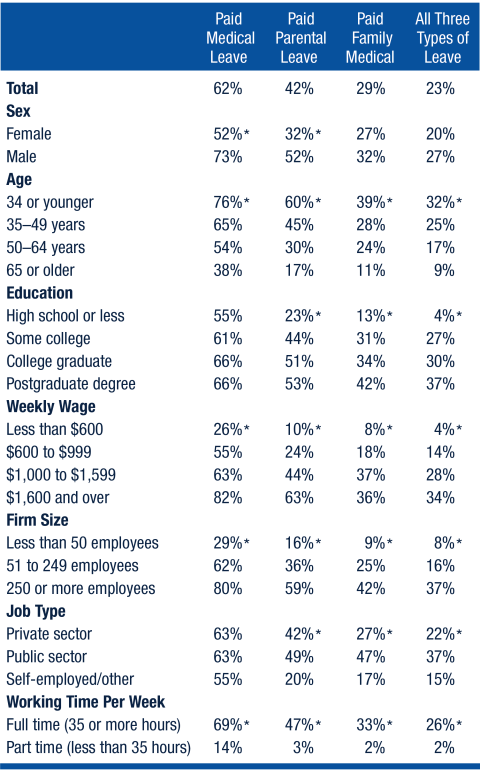

According to Granite State Poll (GSP) data collected in December 2024, 64 percent of New Hampshire workers had any of the three paid family and medical leave benefits. Nearly two-thirds of New Hampshire workers had paid medical leave benefits to tend to their own illness, over one-third had paid parental leave benefits to care for a new child, and over one-quarter had paid family medical leave benefits to care for an ill family member (Figure 1). Overall, one-quarter of New Hampshire workers had paid leave benefits for all three of these family and medical needs.

Figure 1. Workers With Paid Family and Medical Leave Benefits, New Hampshire, 2016 to 2024

Notes: N = 2,310 New Hampshire workers. Estimates are weighted. Statistically significant differences between workers with paid parental leave in 2016 and 2024 at p<.05 and between having all three paid leave types in 2016 and 2024 at p<.05. Source: Granite State Poll, Paid Family and Medical Leave Topical Module, 2016 to 2024.

GSP data collected since 2016 shows that New Hampshire workers’ access to paid medical leave benefits was consistent, with small vacillations in the estimates. Notably, paid parental leave benefits decreased from 50 percent in 2016 to 38 percent in 2024, a decrease of 12 percentage points. Separate analyses indicate that paid parental leave benefits declined among workers with less than a college degree, from 52 percent in 2016 to 25 percent in 2024.

The NH Voluntary Paid Leave program launched at the start of 2023. Despite the longer-term changes between 2016 and 2024, GSP data show no change in the share of workers with medical, parental, or family medical leave benefits between December 2022 (pre-program) and December 2024.

Workers in Small Firms, Lower Earners Lack Paid Leave Benefits

Inequities in access to paid family and medical leave benefits in New Hampshire are clear. Lower shares of women have paid medical and parental leave benefits than men (Table 1).7 Similarly, workers with lower education levels have fewer paid leave benefits than workers with higher levels of education.

Table 1. Percent of New Hampshire Workers With Paid Leave Benefits, by Leave Type, 2023 and 2024

Notes: N = 984 New Hampshire workers. Estimates are weighted. An asterisk (“*”) indicates a statistically significant difference between subgroups at p <.05. Source: Granite State Poll, Paid Family and Medical Leave Topical Module, 2023 and 2024.

Whether workers have paid family and medical leave benefits varies with earnings. Workers who earn between $600 and $999 per week, or about $15 to $25 per hour for 40 hours per week, are less likely to have paid family and medical leave benefits than those with higher earnings, at $1,600 or more per week (55 percent and 82 percent, respectively).8

There is a clear delineation in access to paid leave benefits between workers employed in firms with fewer than 50 employees and firms with more: employees working in smaller firms have much lower coverage.

Workers in New Hampshire are not unique in their lack of paid family and medical leave benefits, as these patterns are typical in states without a comprehensive, universal paid family and medical leave program.9 In contrast, neighboring states with comprehensive programs, such as Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island, cover most workers.10 As a result, by design, these programs, unlike the New Hampshire model, have closed gaps in paid family and medical leave benefits by gender, business size, and other demographic and income-related factors, whereas New Hampshire’s voluntary approach has not.11

About 3 Percent of NH Workers Were Enrolled in NH Voluntary PFML Program in 2025

In the first two- and a-half years of New Hampshire’s Voluntary PFML Program, the program had limited enrollment among New Hampshire workers as a share of the civilian workforce. According to NH PFML administrative program data, 14,712, or about 2.1 percent, of New Hampshire workers (including state employees) were enrolled12 in the program in 2023, the first year of the program (Table 2). Program enrollment grew to 18,450 workers (2.6 percent) by the end of 2024, the second year of the program, and halfway through the third year of the program (end of June 2025), total enrollment was 17,913 workers (2.5 percent).

Table 2. NH Voluntary PFML Program Enrollment Data, 2023 to 2025

Notes: Includes number of workers with active policies, currently enrolled, and eligible to receive NH PFML wage replacement benefits by 12/31/23, 12/31/24, or 6/31/25. Private sector worker calculations combine employer and individual plan workers divided by private sector employment. Source: NH Paid Family & Medical Leave Administrative data: Granite State Family and Medical Leave Insurance Monthly Report, as of December 2023, December 2024, and June 2025. NH Employment Security Current Employment Statistics, All Employees Statewide, for December 2023, 2024, June 2025.

In 2023, state employees represented the largest group of covered employees (8,862 workers), followed by employer-sponsored workers who enrolled in the program through their enrolling firm (5,372 workers). Individual employees opting in to the program were the smallest group (478 workers). In the second year of the program, workers enrolled through their employer grew by almost 3,000 workers to 8,094 workers. Individual employees opting in were still the smallest group enrolled in the program (1,058 workers), despite the overall increase in this type of enrollee. At the end of the second year of the program, 2.1 percent of private sector workers were enrolled in the program. For comparison, between 80 and 90 percent of private sector workers in states with comprehensive programs have paid family and medical leave benefits.13

In 2023, 217 firms opted in to the NH Voluntary PFML program. By the end of 2024 (the second year), 308 firms had active policies in the NH PFML program—less than 1 percent of the state’s 46,564 firms.

Women Overrepresented in Individual Plan

As of June 2025, the demographics of workers enrolled in the employer group plan versus the individual plan differ substantially. Whereas half of enrollees in the employer group plan are female (49 percent), nearly three-quarters of individual plan enrollees are female (73 percent) (Table 3). In addition, a smaller share of those in the employer group were under age 45 (59 percent) compared with those in the individual plan (69 percent). Finally, 64 percent of the employer plan enrollees worked in large firms with 50 or more employees, while 72 percent of the individual plan enrollees did so. Three-quarters of these individual plan enrollees pay the maximum premium of $5 per week.14

Table 3. Characteristics of NH PFML Enrollees by Enrollment Type, 2023 to 2025

Notes: Includes workers with active policies, currently enrolled, and eligible to receive NH PFML wage replacement benefits issued by 12/31/23, 12/31/24, or 6/31/25. Data not available for enrollees in State Employee Plan. A dash (“-”) indicates not applicable. Source: NH Paid Family & Medical Leave: Granite State Family and Medical Leave Insurance Monthly Report, as of December 2023, December 2024, and June 2025.

Less Than One in Five NH Workers Have Heard of the NH PFML Program

Although the program was advertised in local media outlets, lack of awareness about the New Hampshire program may be one reason for the low enrollment among Granite Staters. Data from the GSP between 2022 and 2024 suggest that an average of 18 percent of workers had heard of the NH Voluntary PFML program. There were few differences in knowledge across worker characteristics. However, a higher share of Democrats was aware of the program (23 percent) compared with Republicans (15 percent) or Independents (10 percent). Likewise, program awareness varied by type of job: 32 percent of public sector workers and 27 percent of self-employed workers had heard of the program, compared with just 16 percent of private sector workers.

Is Six Weeks of Paid Leave Enough? Women, Younger Workers Say No

The New Hampshire program covers workers for up to six weeks of leave.15 Typically, comprehensive programs in other states cover workers for up to 12 weeks of leave for qualifying reasons, while some states offer longer leaves for medical reasons and/or add additional weeks for pregnancy complications. Research shows that mothers who return to work prior to 12 weeks are at risk of postpartum depression, and those who return at or before six weeks are particularly vulnerable.16 It is possible that those who consider six weeks of leave inadequate will forego purchasing this product.

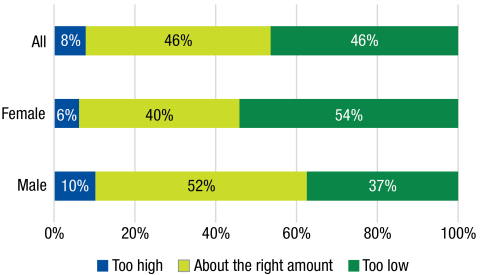

From a public perspective, there is little agreement on the ideal length of leave coverage. In 2023 and 2024, equal shares of New Hampshire workers thought six weeks of leave was the right amount or too low, with both at 46 percent (Figure 2). Eight percent of workers thought that six weeks was too high.

Disaggregating responses on length of leave reveal a substantial gender divide. More than half of employed women believed six weeks was too low compared with just 37 percent of employed men. Since women typically have greater family care responsibilities17 and require time to recuperate after childbirth, it is not surprising that they would view six weeks of paid leave as inadequate to a greater extent than men. Table 4 shows differences also exist by age, marital status, and educational attainment.

Figure 2. Six Weeks of Paid Family and Medical Leave: Is That Enough?

Notes: N = 906 New Hampshire workers. Estimates are weighted. Source: Granite State Poll, Paid Family and

Medical Leave Topical Module, 2023 and 2024.

Is 60 Percent Wage Replacement Enough? New Hampshire Workers Say No

In states that provide comprehensive paid family and medical leave, research shows that leave taking is higher when the reimbursement rate18 is also high. Men and low-income workers give low reimbursement rates as reasons for not taking leave, even when it is paid.19

The NH Voluntary PFML program stipulates the insurance product offered to workers will reimburse a minimum of 60 percent of the covered worker’s usual weekly wage while they are out on leave, up to a maximum of $2,032 per week in 2025.20 States with comprehensive paid leave programs often have a blended rate of reimbursement, with higher rates of wage replacement to lower wage workers (about 80–90 percent wage replacement) and a floor of about 70 percent wage replacement for higher wage workers, up to a benefit cap.21 The relatively low reimbursement rate in the NH PFML program may be a deterrent to program participation.

Table 4. Percent Who Agree Six Weeks of Paid Family and Medical Leave Is Not Long Enough, 2023 and 2024

Notes: N = 906 New Hampshire workers. Estimates are weighted. An asterisk (“*”) indicates a statistically significant difference between subgroups at p <.05. Source: Granite State Poll, Paid Family and Medical Leave Topical Module, 2023 and 2024.

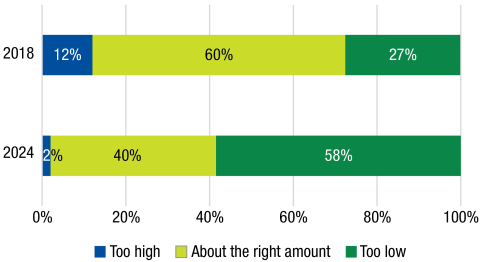

In 2024, a majority of workers—58 percent—believed that 60 percent wage replacement was too low and 40 percent believed it was about the right amount (Figure 3). Only two percent thought 60 percent wage replacement was too high. There has been a shift in opinion since 2018, when 60 percent of New Hampshire workers thought 60 percent wage replacement was about right.

There was strong agreement among New Hampshire workers—more than half of women and men, higher educated and lower educated, married and unmarried, higher earnings and lower earnings all concurred that 60 percent wage replacement was too low (data not shown). Analysis of opinion by political party affiliation shows a majority of Democrats and Independents view 60 percent wage replacement as too low, while a majority of Republicans believed 60 percent was about right.

Figure 3. Responses to “Is 60% wage replacement for paid family and medical leave enough?” 2018 and 2024

Notes: N = 791 New Hampshire workers. Estimates are weighted. Source: Granite State Poll, Paid Family and Medical Leave Topical Module, 2018 and 2024.

Other Program Components May Deter Program Enrollment

There are other program components specific to the NH PFML program which may deter New Hampshire workers and firms from joining. For instance, the individual opt-in period restricted to two months each year (December and January) may impede program sign up as this timing may not coincide with the unknown major life events that change workers’ need for paid leave.

Further, since the NH PFML program does not include job protection outside the National FMLA criteria, the estimated 60 percent of New Hampshire workers employed by firms with fewer than 50 employees or who do not meet the other FMLA criteria are left without job protection if they take the program’s paid leave. Individual workers considering enrollment in the program may not opt in due to the lack of job protection. In 2018, 93 percent of New Hampshire residents supported guaranteed job protection for all workers taking paid family or medical leave.22

In addition, the NH PFML program imposes a one-time waiting period requiring that individual workers opting in to the individual plan pay in to the program for seven months prior to making a claim. A waiting period is not uncommon in comprehensive programs, however a 7-month waiting period is longer than typical.23 The combination of the limited enrollment period and the 7-month waiting period may deter workers from purchasing an individual plan if the timing does not line up with their care needs.

Unmet Need

Nationwide, the lack of paid family and medical leave presents a conundrum for workers, forcing them to choose between meeting family financial needs and family care responsibilities. In 2024, 11.1 million workers nationally needed medical or family leave but did not take it; 7.3 million forwent the leave because they could not afford to take unpaid leave and 2.7 million forwent the leave because they feared losing their job.24 A 2024 report estimated that in a year New Hampshire workers needed 155,000 medical, family, or parental leaves, with 49,000 (31.6 percent) of those leaves not taken.25

Another measure of unmet need is certainty with having enough paid leave from work if confronted with a serious family or medical need requiring a few weeks to a few months away from work. Not surprisingly, workers with lower access to paid family and medical leave are also those who expressed uncertainty that they would have enough leave. Given the unequal paid family and medical leave coverage in New Hampshire, workers with lower education, lower earnings, working in small businesses, or self-employed all report higher uncertainty that they would have enough leave (Table 5).

Table 5. Percent of Workers Who Report Being Uncertain They Would Have Enough Leave If Needed, 2023 and 2024

Notes: “Uncertain” includes those who are uncertain or somewhat uncertain they would have enough leave if a qualifying event occurred. N = 1,052 New Hampshire workers. Estimates are weighted. An asterisk (“*”) indicates statistically significant differences between subgroups at p < .05. Source: Granite State Poll, Paid Family and Medical Leave Topical Module, 2023 and 2024.

Conclusions

The NH PFML program makes PFML insurance available for purchase for workers and employers but does not guarantee coverage. In the first two- and one-half years of the program, it did little at the state level to increase overall paid family and medical leave benefits and maintained inequities in coverage by gender, job type, education level, wage level, and business size. One way to increase paid family and medical leave benefits would be to pass the Family and Medical Insurance Leave Act (FAMILY) Act26 which was recently introduced in the United States Congress (HR. 3481/S. 1714). This Act would go beyond the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) by providing up to 12 weeks of job protected paid leave, reimbursed up to 85 percent of a workers’ wages for low-wage workers and about 67 percent for middle-wage workers, up to a cap of $4,000 per month. The FAMILY Act would cover all workers regardless of firm size, or a worker’s education or earnings, as well as self-employed people. Similarly, the New Hampshire legislature could pass a comprehensive paid family and medical leave program.

If nothing else, New Hampshire lawmakers could strengthen the requirements of the state’s existing voluntary approach to paid leave by: (1) setting an 8-week or 12-week minimum duration; (2) setting a higher minimum for wage replacement; (3) expanding job protection beyond the FMLA’s minimums; (4) reducing the 7-month wait period for individual plan enrollees to become claims eligible; and (5) funding a robust outreach campaign aimed at employers with workers who are disproportionately unlikely to have paid leave benefits. Finally, requiring more disclosure about the industries, employers, and workers who are covered by the New Hampshire program would allow for a more comprehensive understanding of who is being reached by the current program.

In any event, New Hampshire policymakers would do well to consider alternative approaches to increase paid leave benefits for Granite State workers. The New Hampshire workers who recently attained benefits through the NH voluntary paid leave program will likely be better able to facilitate their work and family care responsibilities. But since the majority of New Hampshire workers still lack paid family and medical leave, they are often put in a bind when family care needs arise, forced to choose between receiving a paycheck and meeting family care responsibilities.

Data

This analysis is based on Granite State Poll (GSP) data collected by the University of New Hampshire Survey Center in Winter 2016, October 2018, December 2022, 2023, and 2024, which provides a statewide representative sample of approximately 500–750 households and collects demographic, economic, and employment information. The author developed the Paid Leave Topical Modules that were added to the GSP. In this brief, respondents’ access is reported to different types of paid leave benefits and whether respondents answered “yes” to (1) having paid parental leave to care for a newborn or adopted child, (2) having paid family medical leave to care for a family member with a serious illness or injury, (3) having paid medical leave for themselves when they are seriously ill or injured, or having paid short-term disability leave. The few respondents who stated they did not know or were not sure were excluded from this analysis. All analyses are weighted using person-level weights provided by the University of New Hampshire Survey Center based on U.S. Census Bureau estimates of the New Hampshire population. This brief also reports on NH PFML program administrative data compiled in the Granite State Family and Medical Leave Insurance Monthly Reports with reporting as of 12/31/2023, 12/31/2024, and 6/30/2025. Differences presented in the text are statistically significant at p<.05.

Endnotes

1. Tanya Byker and Elena Patel, “A Proposal for a Federal Paid Parental and Medical Leave Program.” The Hamilton Project, (2021) Brookings Institution, Washington, DC; National Partnership for Women & Families, “Factsheet: Paid Leave Works: Evidence from State Programs.” (2023) Washington, DC.

2. National Partnership for Women and Families. “Factsheet: Paid Leave Means a Stronger New Hampshire.” (February 2025).

3. In the first quarter of 2024, 96 percent of New Hampshire firms had less than 50 workers, representing 41 percent of workers in the state. See NH Employment Security, Firms by Size, Preliminary First Quarter 2024, https://www.nhes.nh.gov/elmi/statistics/fbs.htm

4. Including the District of Columbia. In order of enactment date: CA (2002), NJ (2008), RI (2013), NY (2016), DC (2017), WA (2017), MA (2018), CT (2019), OR (2019), CO (2020) have programs that are fully implemented and providing benefits; MD (2022), DE (2022), MN (2023), and ME (2023) have enacted programs and will begin paying benefits in 2026. For more information on the programs, see National Partnership for Women & Families. “State Paid Family & Medical Leave Insurance Laws.” Retrieved 5 June 2025, from: https://nationalpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/state-paid-family-leave-laws.pdf

5. Virginia, Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Florida, Tennessee, Texas, and South Carolina passed legislation to allow private insurance companies to offer paid family leave as an insurance product.

6. New Hampshire Paid Family and Medical Leave Annual Report, Implementation and Year 1, 2021–2023, https://www.paidfamilymedicalleave.nh.gov/sites/g/files/ehbemt781/files/documents/nh-pfml-2023-annual-report.pdf

7. I combine GSP 2023 and 2024 datasets in Table 2 to increase sample size when comparing access to paid leave across groups (and in subsequent sub-group analyses).

8. This analysis includes full and part-time workers; 10 percent of workers earning between $600 and $999 worked part-time.

9. See the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States” for employee benefits by state: https://www.bls.gov/ebs/publications/employee-benefits-in-the-united-states-march-2023.htm.

10. National Partnership for women and families, “State Paid Family and Medical Leave Insurance Laws.” (2024) https://nationalpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/state-paid-family-leave-laws.pdf

11. National Partnership, “State Paid Family and Medical Leave Insurance Laws.”

12. This includes workers who were enrolled with an active policy and were eligible to make claims and receive wage replacement benefits.

13. Nicholas Perry, “Paid Leave and Job Protection for Parents, People Who Are Sick and People Who Have Sick Family Members in the United States.” World Policy Center. (2024) https://www.worldpolicycenter.org/sites/default/files/2023-06/Policy_Brief_Paid_Family_and_Medical_Leave_in_US_states.pdf;

A Better Balance, “Overview of Family Leave Laws in the United States.” https://www.abetterbalance.org/family-leave-laws/

14. Characteristics of state plan enrollees in the PFML program were not available.

15. Employers may choose to purchase up to 12 weeks of leave for their workers through the New Hampshire program, however the minimum amount required by the program is 6 weeks.

16. J. Jou et al., Paid Maternity Leave in the United States: Associations with Maternal and Infant Health. Maternal and Child Health Journal, (2017) 22(2), 216–225; B. Mandal, “The Effect of Paid Leave on Maternal Mental Health.” Maternal and Child Health Journal, (2018) 22(10), 1470–1476.

17. Melissa Milkie et al., “Who’s doing the housework and childcare in America now? Differential convergence in twenty-first-century gender gaps in home tasks.” Socius, (2025) 11. DOI 23780231251314667

18. The reimbursement rate is the percent of earnings paid while the employee is taking paid leave.

19. Eileen Appelbaum and Ruth Milkman, “Leaves That Pay: Employer and Worker Experiences With Paid Family Leave in California” (2011) Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research; Sarah Fass, “Paid Leave in the States: A Critical Support for Low-Wage Workers and Their Families” (2009) National Center for Children in Poverty, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University; Y. Yang et al., “Paid Leave for Fathers: Policy, Practice, and Reform.” Milbank Q. 2022 100(4): 973–990.

20. The maximum benefit amount is based on 60% of the Social Security wage cap: https://www.metlife.com/insurance/disability-insurance/paid-family-medical-leave/states/new-hampshire

21. National Partnership, “State Paid Family and Medical Leave Insurance Laws.”

22. Kristin Smith, “Job Protection and Wage Replacement: Key Factors in Take Up of Paid Family and Medical Leave Among Lower-Wage Workers.” (2019) Carsey National Issue Brief #141, Durham, NH.

23. National Partnership, “State Paid Family and Medical Leave Insurance Laws.”

24. National Partnership of Women and Families, February 2025. “Key Facts: The Family and Medical Leave Act.” https://nationalpartnership.org/report/fmla-key-facts/

25. Emily Andrews, Sapna Mehta, and Jessica Milli. “Working People Need Access to Paid Leave.” CLASP. (2024) https://www.clasp.org/publications/report/brief/working-people-need-access-to-paid-leave/

26. For more information on the FAMILY Act, see:

The FAMILY Act of 2025 Explainer. https://www.newamerica.org/better-life-lab/blog/family-act-of-2025-explainer/

About the Author

Kristin Smith is a visiting research associate professor of sociology and Director of the Policy Research Shop at the Rockefeller Center at Dartmouth College, and senior fellow at the Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire. Smith’s research focuses on gender inequality, earnings and employment, and work and family policy.

Acknowledgements

New Hampshire Women’s Foundation, through a grant from The Pritzker Foundation, provided support for the analysis and writing of this brief; the Carsey School of Public Policy provided support to produce it. Data collection over the years received financial support from the New Hampshire Women’s Foundation, the Pritzker Foundation, the Rockefeller Center at Dartmouth College, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, and the U.S. Department of Labor Women’s Bureau. This product was created by the author and does not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Labor nor the other funders. The author thanks Dartmouth undergraduate students, Mark Eggener and Miles Groom, for research assistance, and Vicki Shabo, Molly Westin Williamson, MacKenzie Nicholson, Devan Quinn, Jessica Carson, Carrie Portrie, and Laurel Lloyd Earnshaw for substantive comments.

© 2026 University of New Hampshire. All rights reserved.