Key Findings

New Hampshire’s population reached 1,377,529 on April 1, 2020, an increase of 61,000 residents (4.6 percent) since April 1, 2010 according to new 2020 Census data. This increase is smaller than the state’s population gain of 6.5 percent between 2000 and 2010. New Hampshire’s population grew both because more migrants moved to the state than left and because births exceeded deaths. Migration was the most important source of the state’s population increase, accounting for 89 percent of the population gain. Over the decade, New Hampshire had a net migration gain of 54,500 including both those who moved from other states and immigrants. In contrast, there were just 6,500 more births than deaths during the decade, far fewer than in prior decades.

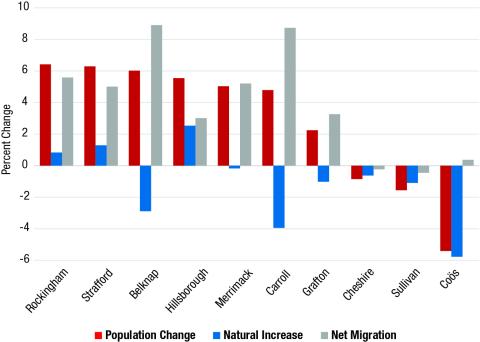

The population grew in seven of New Hampshire’s ten counties between 2010 and 2020 (Figure 1). Migration accounted for most of the population growth in all seven of the state's growing counties. In the two fastest growing counties, Rockingham and Strafford, more than 80 percent of the population gain was from migration, with both counties benefiting from migration gains due to the outward sprawl of the Boston metropolitan area. In four counties, migration was the sole driver of population change as each had more deaths than births. For example, Carroll County is a recreational and amenity area that grew by attracting enough migrants from elsewhere in the Northeast to offset a substantial excess of deaths over births among its aging residents.

Migration also produced most of the growth in Hillsborough County, the state’s most populous county with 418,700 residents. It includes the state’s two largest cities—Manchester and Nashua—as well as a substantial suburban population. Both cities grew by 5.6 percent and most of the gain in each city was due to births exceeding deaths by a significant margin. In the suburbs, the population gain was 5.5 percent with most of the growth from migration.

The population declined in the state’s three remaining counties. Here deaths exceeded births by a wide margin and there was little, if any, migration gain to offset it. In northernmost Coös County, major declines in the traditional wood and paper products industry continue to push young adults to seek opportunity elsewhere, which results in fewer births to offset deaths to its older population. Yet Coös County is also situated in a scenic region with ski areas, resorts, and a strong regional infrastructure that have welcomed generations of vacationers and now amenity migrants. This is reflected in a small migration gain, though it was not sufficient to offset the many more deaths than births.

Figure 1: New Hampshire Demographic Change, 2010 to 2020

Source: U.S. Census, 2010 and 2020 Decennial Census and Census Bureau Population Estimates

Analysis: K.M. Johnson, Carsey School, University of New Hampshire.

The balance between migration and natural change is important to New Hampshire’s demographic future. Migration has long provided most of the state’s population gain. Though migration gains diminished sharply during the Great Recession and its aftermath, they have rebounded over the past five years. In a state where deaths have exceeded births in each of the last four years, migration is critical to the state’s future. New Hampshire traditionally had significantly more births than deaths. But that surplus has dwindled recently due to the growing number of seniors in the state, and because of drug-related deaths to young adults. In contrast, births have diminished modestly because there are relatively few women of child-bearing age and fertility rates are low in New Hampshire, as they are nationwide. The impact of COVID-19 on both mortality and fertility is likely to further diminish births and increase deaths in New Hampshire in the near term. This increases the state’s dependence on migration for future growth and underscores the importance of developing policies that encourage current residents to remain and new migrants to come to New Hampshire.

Methods and Data

Population data are from the 2020 and 2010 Decennial Census. Data on births and deaths to calculate natural change are from the Census Bureau’s Population Estimates program. Births and deaths for July 2019 to April 2020 are estimated using provisional state data from the NCHS-CDC with additional adjustments for New York City. Net migration is calculated as the residual of population change minus natural change. Concerns remain about the quality of the 2020 Census and on the impact of the Census Bureau’s Differential Privacy algorithms on the accuracy of the 2020 Census, but it will be some time before these issues are resolved.

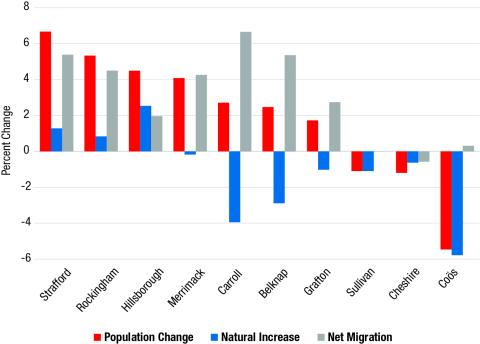

The population declined in the state’s three remaining counties. Here deaths exceeded births by a wide margin and there was little, if any, migration gain to offset it. In northernmost Coös County, major declines in the traditional wood and paper products industry continue to push young adults to seek opportunity elsewhere, which results in fewer births to offset deaths to its older population. Yet Coös County is also situated in a scenic region with ski areas, resorts, and a strong regional infrastructure that have welcomed generations of vacationers and now amenity migrants. This is reflected in a small migration gain, though it was not sufficient to offset the many more deaths than births.

Only in Hillsborough County did the surplus of births over deaths exceed the gain from migration. Hillsborough is the state’s most populous county with 418,700 residents and includes the state’s two largest cities—Manchester and Nashua—as well as a substantial suburban population. Both cities grew modestly, Manchester by 2.7 percent and Nashua by 3.1 percent, in large part because they had many more births than deaths. The population gain was considerably larger (6.0 percent) in the suburban areas of the county and due both to migration gains and more births than deaths.

Figure 1: New Hampshire Demographic Change, 2010 to 2020

Source: U.S. Census, 2010 and 2020 Decennial Census and Census Bureau Population Estimates

Analysis: K.M. Johnson, Carsey School, University of New Hampshire.

The balance between migration and natural change is important to New Hampshire’s demographic future. Migration has long provided most of the state’s population gain. Though migration gains diminished sharply during the Great Recession and its aftermath, they have rebounded over the past five years. In a state where deaths have exceeded births in each of the last four years, migration is critical to the state’s future. New Hampshire traditionally had significantly more births than deaths. But the surplus of births over deaths has dwindled recently due to rising mortality among New Hampshire’s growing senior population, and because of drug-related deaths to young adults. In contrast, births have diminished modestly because there are relatively few women of child-bearing age and fertility rates are low in New Hampshire, as they are nationwide. The impact of COVID-19 on both mortality and fertility is likely to further diminish births and increase deaths in New Hampshire in the near term. This increases the state’s dependence on migration for future growth and underscores the importance of developing policies that encourage current residents to remain and new migrants to come to New Hampshire.

Methods and Data

Population data are from the 2020 and 2010 Decennial Census. Data on births and deaths to calculate natural change are from the Census Bureau’s Population Estimates program. Births and deaths for July 2019 to April 2020 are estimated using provisional state data from the NCHS-CDC with additional adjustments for New York City. Net migration is calculated as the residual of population change minus natural change. Concerns remain about the quality of the 2020 Census and on the impact of the Census Bureau’s Differential Privacy algorithms on the accuracy of the 2020 Census, but it will be some time before these issues are resolved.

About the Author

Kenneth M. Johnson is senior demographer at the Carsey School of Public Policy, professor of sociology at the University of New Hampshire, and an Andrew Carnegie Fellow. His research was supported by the New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station in support of Hatch Multi-State Regional Project W-4001 through joint funding of the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under award number 1013434, and the state of New Hampshire. The opinions are his and not those of the sponsoring organizations. The research assistance of Kristine Bundschuh is gratefully acknowledged.