download the brief

Key Findings

Population changes reinforce available economic opportunity: in-migrating retirees require amenities and services, spurring demand for low-wage work, while out-migrating young workers deplete the workforce for potential new businesses.

Rural residents often work multiple low-paid formal jobs or patch together formal and informal opportunities. The nature of work varies by the local economic and geographic context.

Northern New England is a rapidly aging region, and its rural places in particular face substantial losses of young and working-age people.1 These population changes influence the kinds of economic opportunities that are available. In this brief, we use interview and focus group data to explore how residents view the economic opportunities in two rural Northern New England counties and how these opportunities are related to migration patterns. Because the retention of working-age people is key for local workforce and regional vitality, we explore how these changes intersect within the different historical and economic contexts of two communities. We suggest that those working to help rural communities thrive consider the dynamic interaction of economic opportunities, work supports, and population change.

Economic Opportunities Shape Who Stays and Who Goes

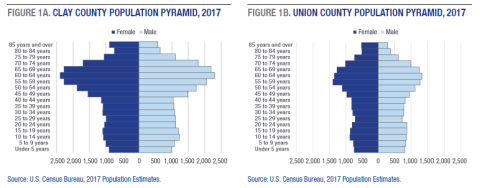

Clay County, which comprises national forest land, state parks, dozens of lakes and ponds, and several ski destinations, is known for its natural beauty. Clay’s abundance of natural amenities also means that it is a retirement destination: 35.5 percent of its population is age 65 or older, compared with 25.5 percent across Northern New England.2 This, coupled with Clay’s status as a tourist destination, translates to about one-quarter of Clay workers being employed in accommodation and food services. Between these industries’ low wages and the share of housing stock consumed by retirees and seasonal tourists, Clay’s economic structure has serious implications for young workers looking to live and make ends meet. One Clay County service provider noted, “The great majority of our jobs are low paying and seasonal and so that is an issue. [And] even if you want that low-paying seasonal job, you cannot find housing that you can afford.” The prevalence of retirees and the economy’s effects on working-age people is visible in Clay County’s population pyramid (Figure 1A). This figure, reflecting the size of both male and female populations by age, shows the large numbers of Clay residents age 55–69 and the relatively few age 40 or younger.

Union County is significantly more remote than Clay County, and has a long tradition of natural resource extraction and related manufacturing and less emphasis on tourism. Historically, these industries provided plentiful work and related population growth, but with an ever-expanding global economy, the isolated Union County faced domestic and international competition around cheaper goods and lower infrastructure costs. As one resident explained, “It’s very expensive to run a mill [here] all year round, because of the heating and all that and so you just saw…this mass exit of all of the mill industry in this area. They found cheap labor somewhere else.” Closely connected to the region’s changing employment options, Union County began losing residents in the latter decades of the 20th century, and in recent years the size of the population in their 50s and 60s has stayed relatively stable while the number of their children who still live in the county has fallen dramatically. As one Union County provider said, “The young people, they’re getting out of school now, [and] there’s nothing for them….They’re graduating from college and if they want a job, they got to go away. They can’t stay, because there isn’t that much for work.” As in Clay County, the population in Union is heavily skewed toward older residents, as shown in the population pyramid in Figure 1B. The figure also demonstrates that Union County has a much smaller overall population than Clay, despite occupying nearly three times the land area.

Quality of Jobs Left Behind

For Clay service providers and residents alike, one of the most pressing issues facing the county is employment, though not necessarily the availability of employment. Instead, residents describe the quality of employment as more problematic, recognizing that the prevalence of seasonal, part-time, and low-paying work is inherent in Clay’s tourism- and retirement-based economy. One provider mused, “I feel like you don’t hear that very often: ‘I can’t find work.’…[The jobs are] not ideal and there’s not a lot of upward mobility and there’s not a lot of pay and there’s not a lot of benefits, but I think people would tell you that they feel as though they can work if they want to.” Another Clay resident confirmed this impression: “That’s why you got so many people working so many jobs. The pay is not enough to compensate [for] the cost of living.”

Data on Clay’s business patterns reveal why residents feel that low-paying jobs are prevalent. Figure 2A shows the percent of Clay workers in each of the county’s five largest industries, based on number of paid employees, and the percent of all Clay County payroll dollars that go to workers in each industry.3 The 45.8 percent of workers concentrated in accommodation, food services, and retail take home just 33.9 percent of all county payroll dollars. “Second home owners [are] coming on the weekends and they’re being served by the people that live in the [county] through the hotels and the restaurants,” explained one Clay community member.

In contrast to Clay County, Union County is more remote and has a much smaller tourist industry. Figure 2B shows that while retail is also important in Union, health care and social assistance employ significant shares of Union’s population. Employees in this sector receive a relatively equitable share of payroll dollars in the aggregate, whereas retail workers claim a disproportionately small share and those in manufacturing considerably more. As a result, a larger share of formally employed residents in Union County are decently paid (although Union County does have a higher share of workers who aren’t employed full time year round).4

For employees not in health care or manufacturing, survival in the sparsely populated Union County can be especially difficult. When asked how she makes ends meet, a single mother said, “I don’t....We ran out of money Monday. I get paid Friday…it’s just a lifestyle. You adjust to not having and not doing.” For residents like this mother, and many others, making ends meet in recent memory has always included some elements of scarcity, seasonal work, and patching together a living. As one provider said, “I’ve always seen Union County as a [place] where a lot of people got by, by doing a number of different things during the year.”5 A Union County carpenter explained how this patchwork approach worked in practice: “I just can’t rely on carpentry around here to keep the ball rolling. I’ve always grown a big garden.…I’ve sold organic vegetables privately and also to restaurants and whatnot....I’ve got a number of trees planted—more fruit trees, a variety. I do a lot of jams and jellies. I’ve sold a lot of my produce at the farmers’ market in the past as well, to help keep the ball rolling. I own a bunch of land. I cut a lot of my own firewood. And I’ve cut and sold firewood in the past when I’m not doing carpentry and not doing gardening and other things to keep the ball rolling in that regard….I [also] was a captain of an aquaculture boat.…It gave me a fallback as well.”

This irregular economy is reflected in Union’s employment statistics. Only 45.4 percent of residents age 16–64 work year round, with even fewer working full time year round (37.7 percent), considerably less than in surrounding counties.6 The low share of residents working year round speaks specifically to the seasonality of Union’s economy, a structure that for many providers has deep connections to the region’s culture and history. One Union resident explained, “A lot of people…survive on part-time jobs. You know, they fish in the summertime. They drive the school bus in the winter time or work [in] an accountant’s office or whatever. They just cobble together a decent life—not great but that’s how they work.” In its reliance on multiple jobs, Union County is like Clay County, although in Union, residents more often mentioned informal jobs as part of the mix.

Shortfalls in Labor Readiness Among Those Left Behind

In both Clay and Union Counties, residents identify the loss of young workers as a key factor in each area’s inability to attract new businesses and, in turn, the lack of economic opportunities as a driver of young people’s moving away. One Union County provider explained, “We have done a lot of work with the investors behind [a new manufacturing plant in the region] to figure out a training and recruitment strategy where they can fill the eighty jobs they’re creating and they were concerned that they wouldn’t be able to, given just the number of people in the local workforce.” While population size is less often a concern in Clay County, providers in both counties expressed concern about the quality of the workforce left behind when young people leave the region. Talking about the share of local students who graduate high school and do not leave the county for college or work, one Clay provider said, “Forty percent [of the graduating students] stay here and…[they] are not ready for work, never mind skilled….A lot of our existing employers have no problem training a worker who’s ready to work, but they’re not ready.…” When asked what “not ready” meant, the provider explained that residents don’t necessarily have the “soft skills” that teach them to “show up, look well, [and] be polite.” With this lack of skilled labor, businesses may be reluctant to locate in the regions. And as a result, as one Clay community member explained, “My advice to a lot of people is get out of town. You can’t do it here. You need to go someplace where…you’re closer to work, you’re closer to the market.” This sentiment is both an honest reaction to Clay’s economic climate and a contributing factor to that climate.

Implications for Policy and Practice

In both Clay and Union Counties, local stakeholders are prioritizing strategies that focus on both the community and its people (that is, “place-based” and “people-based” strategies), including community economic development and workforce strengthening. Economic diversification is one strategy, as one Union provider explained: “To be honest, we have to kind of try anything we think may work.…You just can’t chase smokestacks….You also need a whole group of locally owned and controlled small businesses, so you have decent multiplier effects.” However, even these kinds of efforts are not without tension in small New England counties, as evidenced by recent research.7 Some efforts work directly with employers to develop customized training programs and focus on channeling residents into training opportunities that more precisely match the region’s labor market. Others are thinking critically about expanding the supports that workers need: “In order to get young entrepreneurs here…we need to make sure that they can have a rental property that they like or buy a house—that they can afford to do that.”8

The challenge of retaining working-age people in remote areas is not new, nor is it unique to Clay and Union Counties. Existing research suggests that retention issues cross professions (for example, health workers and teachers)9 and regions (such as New England and the Midwest).10 Although some programs exist to promote the retention of young workers—including loan forgiveness and tax incentive programs—the scale of these programs is unlikely to offset the population shifts in most places. Instead, policymakers and practitioners should begin thinking about ways to retain workers other than just young college graduates, including by intensively preparing community college and vocational school attendees for the labor market and by continuing to encourage partnerships between regional industry and educational players to assess the fit between training and labor market outcomes.11 In addition, there is evidence that Hispanic in-migration can revitalize local economies and help replenish rural places’ working-age populations. While immigration can have complex implications—for instance, changing cultural dynamics or straining resources for newcomers—there are ways to embrace the process to encourage opportunity for all rural residents.12 On a national scale, efforts to strengthen rural economies—especially places previously supported by single-product extractive industries (for example, timber or mining)—can help to dampen population loss from these places and make them viable communities for working families.

Data and Methods

This brief is adapted from a related journal article forthcoming in the Journal of Rural Social Sciences. The data used in this brief come from the qualitative Carsey Study on Community and Opportunity, conducted between 2011 and 2015 via three focus groups in Union County, two focus groups in Clay County, and twenty-nine interviews in each place, for a total of eighty-five participants. Data were transcribed and analyzed for emergent themes in NVivo 10. For full details on the study’s recruitment and analysis strategies, see the corresponding papers.13 To protect the privacy of people in these small communities, we withhold details about people’s specific professions and personal lives. All the themes discussed emerged from our analyses of these data; however, the qualitative data are supplemented in this brief with data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (2016 five-year estimates), the 2000 and 2010 Decennial Censuses, 2016 Population Estimates, and the 2015 County Business Patterns to situate themes within the broader population context. All sources are noted where applicable.

Box 1. About the Study on Community and Opportunity Series

What is it like to live through the challenges confronted by vulnerable families? In our Study on Community and Opportunity series, we use data from five years of interviews and focus groups with residents, social service providers, and community members (eighty-five participants in all) from two rural New England communities to provide an in-depth examination of the issues that affect vulnerable families and to document the everyday challenges rural residents face as they try to make ends meet.

The study covers a wide range of topics pertaining to how people make ends meet in two different kinds of rural places. We call one community Union County, where a remote location and a seasonal, natural-resource-based economy have generated a history of poverty, and the other, Clay County, where a vibrant mix of natural amenities and a relatively central location attracts wealthy retirees and tourists from within and outside the state. Talking with people in these communities, we learned about their efforts to find and keep work, the use and adequacy of the social safety net, and some of the challenges and advantages of living in a rural community. In this brief, we explore the ways that economic opportunities and population changes interact in each of these places, grounding residents’ stories in quantitative data where possible.

Endnotes

1. For example, the average median age in Northern New England at the 2000 Census was 37.8; in 2010 it was 41.8 (this is based on our calculation of a population-weighted average of Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont’s median ages, using data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2000 and 2010 Decennial Censuses). Further, the Federal Reserve of Boston has found that New England retains a lower share of recent college graduates than any other Census division (Alicia Sasser Modestino, “Retaining Recent College Graduates in New England: An Update on Current Trends,” Policy Brief No. 13-2 (Boston, MA: New England Public Policy Center at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 2013).

2 Authors’ calculation of U.S. Census Bureau’s 2016 Population Estimates.

3. Note that Figures 1A and 1B are replicated from the corresponding manuscript accepted for publication at the Journal of Rural Social Sciences, although the figures here draw on updated data (2015 instead of 2013). However, the patterns in both years are the same.

4. See Marybeth J. Mattingly and Jessica A. Carson, “I have a job…but you can’t make a living”: How county economic context shapes residents’ livelihood strategies.” Accepted for publication in Journal of Rural Social Sciences.

5. Note that the importance of informal work for rural residents has been well documented. For instance, see Leif Jensen, Jill L. Findeis, Wan-Ling Hsu, and Jason P. Schachter, “Slipping Into and Out of Underemployment: Another Disadvantage for Nonmetropolitan Workers?” Rural Sociology 64, no 3, (1999): 417–38; and Tim Slack, “Work, Welfare, and the Informal Economy: Toward an Understanding of Household Livelihood Strategies,” Community Development 38, no. 1 (2007): 26–42.

6. Authors’ calculations of U.S. Census Bureau’s 2016 American Community Survey five-year estimates.

7. Michele M. Dillon, “Forging the Future: Community Leadership and Economic Change in Coös County, New Hampshire” (Durham, NH: Carsey School of Public Policy, 2012).

8. For more on the challenges and opportunities around housing in these communities, see Jessica Carson and Marybeth J. Mattingly, “’Not Very Many Options for the People Who Are Working Here’: Rural Housing Challenges Through the Lens of Two New England Communities,” National Issue Brief #128 (Durham, NH: Carsey School of Public Policy, 2017).

9. David H. Monk, “Recruiting and Retaining High-Quality Teachers in Rural Areas,” The Future of Children 17, no. 1 (2007): 155–174.

10. See Georgeanne Artz, “Rural Area Brain Drain: Is It a Reality?” Choices 18, no. 4 (2003):11–15; and Patrick J. Carr and Maria J. Kefalas, Hollowing Out the Middle: The Rural Brain Drain and What it Means for Rural America (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2009).

11. See Carr and Kefalas, 2009.

12. See Patrick J. Carr, Daniel T. Lichter, and Maria J. Kefalas, “Can Immigration Save Small-Town America? Hispanic Boomtowns and the Uneasy Path to Renewal,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 641, no. 1 (2012): 38–57.

13. Mattingly and Carson, “I have a job…but you can’t make a living,” and Jessica A. Carson and Marybeth J. Mattingly, “‘We’re All Sitting at the Same Table’: Challenges and Strengths in Service Delivery in Two Rural New England Counties,” Social Service Review 92, no. 3 (2018): 401–431.

About the Authors

Beth Mattingly conducted this work in her capacity as a policy fellow at the Carsey School of Public Policy and in her previous role as director of Carsey’s Vulnerable Families Research Program. She now maintains her role as a policy fellow at Carsey and is an assistant vice president in the Regional and Community Outreach Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

Jess Carson is a research assistant professor with the Vulnerable Families Research Program at the Carsey School of Public Policy. Since joining Carsey in 2010, she has studied poverty, work, and the social safety net, including policies and programs that support low-income workers like affordable health insurance, food assistance programs, and quality child care.

Acknowledgments

The authors express deepest thanks to the participants in the Carsey Study on Community and Opportunity, who kindly shared their stories and helped us understand their communities. The authors also thank Michael Ettlinger, Curt Grimm, and Michele Dillon at the Carsey School of Public Policy for feedback on earlier drafts of this brief, and Laurel Lloyd at the Carsey School for her assistance with layout. Thanks also to the anonymous reviewers and editor at the Journal of Rural Social Sciences, whose comments strengthened this work.

This research was made possible by Grant Number 90PD0275 from the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.