Key Findings

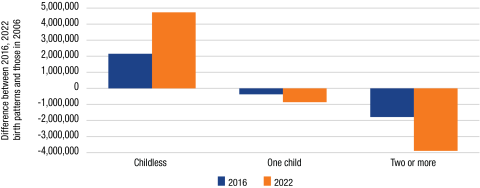

In 2022, there were 21.9 million women aged 20–39 who had not given birth in the United States. This is 4.7 million more childless women of prime child-bearing age than would have been expected given fertility patterns prior to the Great Recession, up from 2.1 million in 2016 (Figure 1). In 2022, there were 9 percent more women 20 to 39 than in 2006, but the share who had never had a child was up by 37 percent.1 Had pre-recessionary fertility patterns continued, more than 80 percent of these 4.7 million childless women would have given birth to two or more children by 2022, and the remaining 20 percent would have had a single child.

Factors Influencing Fertility and Childbearing

Initially, the Great Recession was thought to have caused women to delay births that they would even-tually make up as the economic and social turbulence of the era faded. Yet, 15 years later, fertility rates remain near record lows, and the number of childless women continues to rise. In addition to the Great Recession and Covid, changing social, demographic, economic, and cultural factors also influenced attitudes about fertility, marriage, and children. These include greater educational and employment opportunities for women, the growing expense of children, limited access to child¬care and family leave, and changing patterns of cohabitation and immigration. Lower marriage rates account for much of the increase in childlessness because fertility among women who have married is higher than among those who have not married. But, the number of married women who have not had a child is also higher than expected given historical trends.

Figure 1. Gap Grows Between Expected and Actual First Births to Women 20 to 39

Analysis: K.M. Johnson, Carsey School, UNH. Source: Current Poplation Survey, U.S. Census Bureau

The cumulative result of fewer women having children and diminishing fertility levels was 9.6 million fewer U.S. births between 2008 and 2022 than if pre-recession fertility rates had been sustained.2 There were 655,0000 fewer births in 2022 than in 2007—a 15.1 percent decrease—even though the number of women in their prime childbearing years (aged 20–39) rose by 9 percent. Fertility rate declines were greatest among women under 30, where childless rates increased the most. Fertility rates diminished slightly among women in their early 30s and increased modestly among women 35 to 49. However, fertility gains among older women were too small to offset the significant fertility declines and increased childlessness among younger women.

The course of future childbearing and fertility remains to be seen. Certainly, some women who have delayed children will still have them, but the substantial rise in the proportion of childless women suggests that at least some will forego children. These fertility and child-bearing decisions have significant implications for health care, schools, child-related businesses, and eventually for the labor force.

Methods and Data

This analysis is based on data from the Census Bureau Current Population Survey from 2006 through 2022.

Endnotes

- Women aged 20–39 accounted for 92 percent of all births in 2022. Natality Data 2022. National Center for Health Statistics, CDC. https://wonder.cdc.gov/natality-expanded-current.html

- Johnson, Kenneth M. 2023. “U.S. Births Remain Near 40-Year Low for Third Consecutive Year.” Data Snapshot. June 5, 2023. Durham, NH: Carsey School of Public Policy.

About the Author

Kenneth M. Johnson is senior demographer at the Carsey School of Public Policy, professor of sociology at the University of New Hampshire, and an Andrew Carnegie Fellow.