download the brief

What Are Head Start and Early Head Start?

Founded in 1965, Head Start is designed to promote “school readiness of children under 5 from low-income families through education, health, social, and other services.”1 Created in 1994, Early Head Start focuses specifically on the youngest children—those under age 3, and pregnant women—and provides “early, continuous, intensive, and comprehensive child development and family support services to low-income infants and toddlers, and their families, and pregnant women and their families.”2 The Administration for Children and Families, housed within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, oversees and administers all Head Start programs through the federal Office of Head Start.

Head Start Locations and Enrollment In Maine

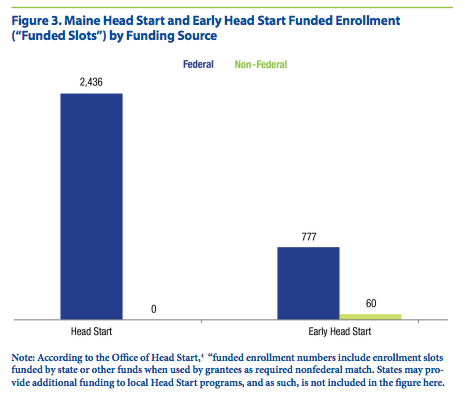

The state of Maine has sixteen Head Start grantees, operating eleven Head Start (HS) programs, three American Indian & Alaska Native Head Start (AIAN HS) programs, and thirteen Early Head Start (EHS) programs (see Table 1). In the 2015–2016 program year, sites operated by these sixteen grantees served 4,126 children and pregnant women.3

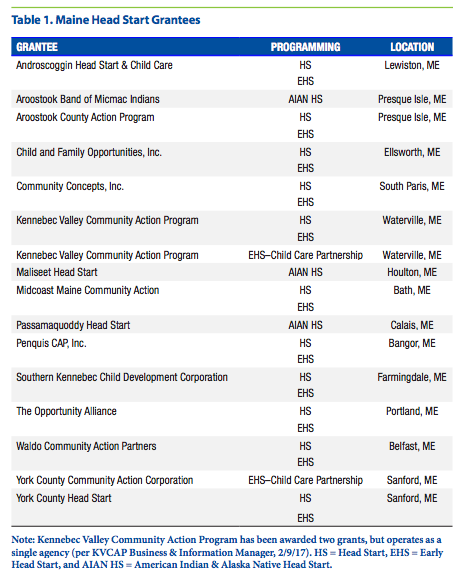

The majority of Maine Head Start enrollees (88 percent) participate in a center-based program; the most popular program option is part-week (four days) enrollment in a center (Figure 1). Most children (91 percent) enrolled in part-week programs are also enrolled for part-day programming (6 hours or fewer per day).

Home visitation is the most prevalent arrangement among Early Head Start enrollees (47 percent) (Figure 2). This option includes weekly 90-minute visits from a home visitor and twice-monthly group activities for enrolled parents and children.

Who Pays for Head Start?

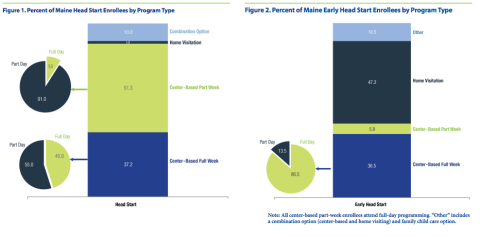

Head Start and Early Head Start programs are funded with grants from the federal government. Each year, Congress authorizes the amount of federal spending allocated to Head Start for the year, and grants are awarded directly to the agencies that operate programs in local communities (including public agencies, private organizations, tribal governments, and school systems). Additional funds or in-kind contributions are provided by state or local sources, or through other mechanisms like grants awarded to individual agencies [see Figure 3, although not all state funds are captured here (see figure note)].

Federal funding for Maine Head Start programming remained relatively stable between 2004 and 2008 (Figure 4). In 2009, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act increased investment for the purpose of expanding enrollment and improving the quality of the Head Start workforce. In 2013, Head Start experienced the largest funding cut in its history due to the federal budget sequestration. Congress restored these funds in 2014.5

In fiscal year 2015, funded enrollment (or the number of available program slots) in Maine Head Start and Early Head Start reached 3,363 (Figure 5). A noticeable decrease in funded enrollment occurred in 2013, related to the budget sequestration (see also Figure 4). Funded enrollment remained slightly lower than pre-sequestration levels, perhaps related to changes in program regulations around increased program quality that meant less spending for enrollment.6

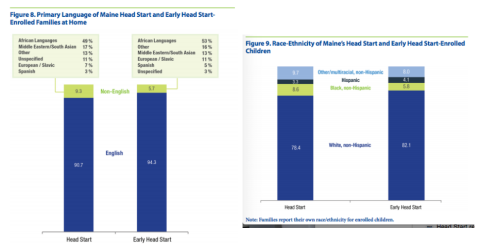

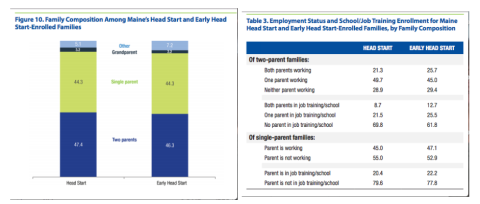

Characteristics of Enrolled Children and Families

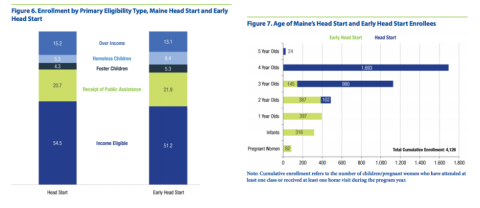

Head Start and Early Head Start programming prioritizes the enrollment of poor families. Eligibility is established, in part, using the federal poverty guidelines (Table 2),7 and families who are poor are eligible for Head Start and Early Head Start services. In Maine, in program year 2015–2016, there were 3,273 funded slots for more than 14,000 poor children under age 5,8 or less than a quarter of those needed to serve all potentially income-eligible children.

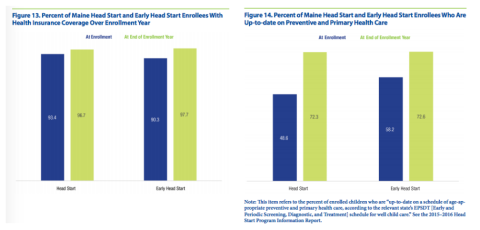

In addition to poor families, certain families with higher incomes may be eligible for Head Start or Early Head Start, including if a child is homeless, is in foster care, or is the recipient of public assistance. While more than half of Maine’s enrollees were eligible primarily because of their families’ below-poverty incomes, about one-fifth were eligible because they received public assistance (Figure 6).9

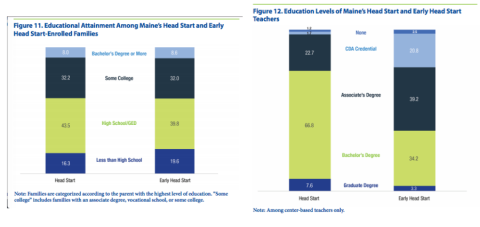

Head Start Staff

The Office of Head Start requires that at least half of the nation’s center- based Head Start teachers have at least a bachelor’s degree in early childhood education or a related field, and that Early Head Start teachers have a minimum of a Child Development Associate (CDA) credential.12 Exceeding the national goal, nearly three-quarters of Maine’s Head Start teachers have a bachelor’s degree, while more than 97 percent of Early Head Start teachers have at least a CDA credential (Figure 12). Education levels are even higher among Maine’s Early Head Start home visitors, 65 percent of whom have at least a bachelor’s degree.

Family Services

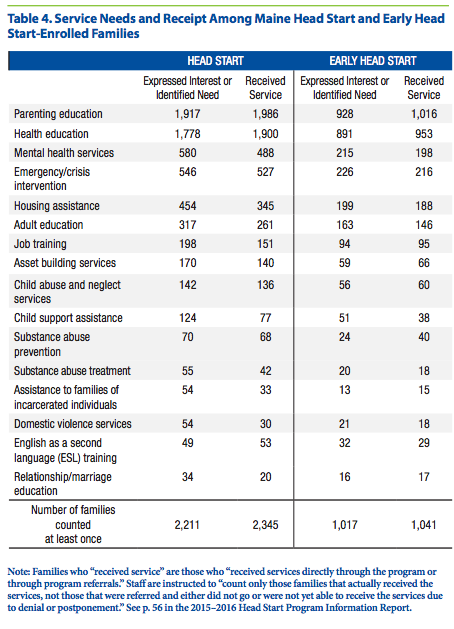

One important component of Head Start is the support that entire families receive from the program staff. Staff refer families who need help to different kinds of emergency and non-emergency services within the community, including assistance with housing, health, substance abuse, or parenting education. More than 3,000 Head Start and Early Head Start families received some kind of service in the 2015–2016 program year.

Box 1. Barriers to Serving Eligible Families

Not all eligible children in Maine receive Head Start or Early Head Start services, and slots exist for less than a quarter of poor children. Limited funding is a major barrier to serving all eligible families, although other barriers exist. Maine Head Start directors cite transportation challenges, mismatches between program hours and families’ work schedules, and the intensity of program expectations around attendance and participation as potential barriers to families’ initial and continued enrollment.10

Box 2: Parents in the Classroom

One important source of program staff are Head Start parents themselves: several program directors describe substitute teaching as a way to get parents involved and as a way to introduce a potential employment pathway to those parents. Indeed, of the more than 1,300 people employed by Maine Head Start programs, 22 percent are current or former Head Start parents.

Almost 3,000 current and former Head Start parents volunteered in Maine Head Start classrooms in the 2015–2016 program year, making up more than two-thirds of all classroom volunteers.

Box 3. Staff Turnover

About 13 percent of Maine Head Start teachers and 10 percent of Early Head Start teachers departed the program during the 2015–2016 program year. Among teachers who left, 28 percent left to seek higher compensation and/or benefits in the same field.

Box 4. Community Relationships

One important characteristic of Head Start programming is its embeddedness within the community. Several Head Start directors note the importance of “relationships with community partners” for “connecting [families] with community resources,” including those related to education, safe housing, access to food, and mental health services.

Endnotes

1. Office of Head Start, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ohs.

2. Ibid.

3. Note that this number indicates cumulative enrollment; that is, all children and women “who have been enrolled in the program and have attended at least one class or, for programs with home-based options, received at least one home visit.” Definition from 2015–2016 Program Information Report form; newer forms are available at https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/data-ongoing-monitoring/article/program-in.... Unless otherwise noted, data for this report are sourced from the Office of Head Start’s Program Information Reports; calculations are the author’s own. Access to these data are available upon request through the Office of Head Start, via the Head Start Enterprise System. See https://hses.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/pir/ for contact information.

4. “Head Start Program Facts, Fiscal Year 2015,” https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/data-ongoing-monitoring/article/head-start....

5. For details on the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act expansion, see https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/about/ohs/history/timeline, 2009. For details on the sequestration-related cuts, see https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/about/ohs/history/timeline, 2013. See also https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/08/19/stateline-head-sta... and https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/head-start-eliminated-ser....

6. Specifically, changes to Head Start staff education requirements at the individual level became effective October 1, 2011, while benchmarks for the nation as a whole became effective September 30, 2013. For more details, see “Statutory Degree and Credentialing Requirements for Head Start Teaching Staff, ACF-IM-HS-08-12,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/archive/policy/im/acf-im-hs-08-12-attachment.

7. “U.S. Federal Poverty Guidelines Used to Determine Financial Eligibility for Certain Federal Programs,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, https://aspe.hhs.gov/2015-poverty-guidelines. Note that these poverty guidelines vary from the official poverty thresholds used by the U.S. Census Bureau and others, which vary by age as well as by household size. For more detail on the official poverty thresholds, see https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/histo....

8. The number of poor children is an estimate derived from author’s analysis of American Community Survey 2015, 5-year microdata (IPUMS-USA, University of Minnesota, www.ipums.org). Note that this calculation uses 5 years of Census data to accurately estimate the number of poor, young children in Maine, so the time periods for funded enrollment and poor children differ (2015–2016 program year versus 2011–2015 ACS data). Also note that data do not allow for estimation of the number of poor pregnant women, so the target population is actually larger than that listed here. The Census estimation of poor children uses the statistical definition of poverty, rather than the Department of Health and Human Services version, so there is slight variation between those thresholds. Finally, because poverty is not the only indicator of eligibility (others include homelessness and foster child status), the universe of actually eligible potential enrollees in Maine is much higher than the estimated number of poor.

9. Generally, “over income” refers to children with family incomes between 100 and 130 percent of the poverty guidelines. However, a host of statutory exceptions exist; for example, programs in very remote communities can set different eligibility criteria, as can AIAN programs, provided that other guidelines are being met. For more detail on these exceptions, see Head Start Policy & Regulations, Section 645. Participation in Head Start Programs, https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/policy/head-start-act/sec-645-participatio....

10. Data cited as derived from “Head Start directors” were collected via telephone interview by the author in May and June 2017. More details about this component of the project are available from the author upon request.

11. See, for example, James Cook, “African Immigrants to Maine Are Young, Educated, and Integrating,” Central Maine.com, January 7, 2016, http://www.centralmaine.com/2016/01/07/african-immigrants-to-maine-are-y...

12. Section 1302, Subpart I: “1302.91 Staff Qualifications and Competency Requirements,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start, https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/policy/45-cfr-chap-xiii/1302-91-staff-qual....

13. Note that because the Program Information Report data do not provide a count of children enrolled at the start and end of each program year, percentages in these figures are calculated as a share of cumulative enrollment (that is, as a share of the number of children who attended at any point during the year). As a result, these percentages are underestimates, because not all of the cumulatively enrolled children were necessarily enrolled at the start and end of the program year.