download the brief

Key Findings

Net migration gains to New Hampshire increased because fewer people left the state, and in-migration grew modestly.

Net income gains from migration increased substantially during the pandemic because more high-income households moved to New Hampshire.

New Hampshire’s largest migration gain is from Massachusetts.

New Hampshire continued to gain population during the pandemic even though deaths exceeded births. In each of the past seven years, New Hampshire’s entire population gain has come from migration. Migration is a dynamic process including both an inflow of migrants to the state and an outflow of migrants to other places. The focus of this brief is New Hampshire’s migration gain from domestic migration: more U.S. residents are moving to New Hampshire than leaving the state to live elsewhere in the country. Migration benefits New Hampshire not only by replenishing an aging population, but also because migrants bring significant expertise, resources, and income.

New Hampshire Increases Net Migrant and Cash Flows During Pandemic

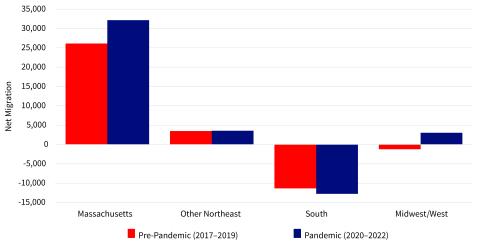

During the era of the Covid pandemic (2020–2022), New Hampshire had a net migration gain of 26,000 (Figure 1). This was a significant increase from the net migration gain of 17,000 in the three years prior to the pandemic (2017–2019). Most of the migration gain was due to fewer people leaving the state during the pandemic, a trend consistent with that elsewhere in the United States. Specifically, only 113,000 migrants left the state from 2020 to 2022 compared to 121,000 outmigrants from 2017 to 2019. In contrast, there were 139,000 migrants to the state between 2020 and 2022, compared with 138,000 between 2017 and 2019.

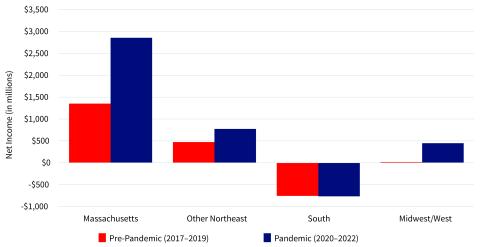

In addition to their contribution to the state’s population gain, migrants to New Hampshire earn considerably more than those who leave. Households migrating to New Hampshire during the pandemic earned an average of $111,000 compared to $87,000 for households leaving the state. The net income advantage to New Hampshire from such migrant exchanges is substantial. In the three years prior to the pandemic, migrants to New Hampshire collectively earned $1.1 billion more than those who left (Figure 2). Between 2020 and 2022, this figure tripled to $3.3 billion as New Hampshire attracted higher-income migrants.

Figure 1. The Net In-flow of Migrants to New Hampshire from Other States and Regions Increased During the Pandemic

Source: Internal Revenue Service–Migration Data. Analysis: Kenneth Johnson and Tyrus Parker, Carsey School, UNH.

Figure 2. New Hampshire’s Net Income Gain from Migration Increased During the Pandemic Because Migrants to the State Earned More Than Those Leaving

Source: Internal Revenue Service–Migration Data. Analysis: Kenneth Johnson and Tyrus Parker, Carsey School, UNH.

Massachusetts Is the Largest Source of New Hampshire Migrants

The largest source of migrants and income to New Hampshire comes from Massachusetts. The net migration gain from Massachusetts grew by 23 percent from 26,000 in 2017 to 2019 to 32,000 during the pandemic. However, the net income gain from the migration exchange between Massachusetts-New Hampshire more than doubled, rising from $1.4 billion in the pre-pandemic era to $2.9 billion during the pandemic. New Hampshire also received a modest net influx of migrants from elsewhere in the Northeast, which contributed both to an increase in the state’s population and income. In contrast, New Hampshire has long experienced a net migration and income loss to states in the South, notably to Florida.

New Hampshire is not the only state that gained migrants and income during the pandemic. Neighboring states Maine and Vermont also experienced recent migration increases. Net domestic migration to Maine increased from 21,000 before the pandemic to 33,000 during the pandemic and income gains from migration grew from $1.2 billion to $2.5 billion. Vermont had a net migration loss of 1,900 before the pandemic but gained nearly 7,500 migrants during the pandemic, while income among in-migrants outpaced that among leavers by $1.1 billion.

Migration Has Both Demographic and Economic Benefits for New Hampshire

New Hampshire continues to benefit from migrants to the state from elsewhere in the United States. Such domestic migration to New Hampshire accounted for most of the state’s recent population increase, although immigration also contributed to the state’s growth. Migrants to New Hampshire from other states tend to be in their prime working years and bring considerable talent, education, and expertise that enhances the state’s labor force. As we show here, they also earn substantial incomes that contribute to the state’s economy. A key question is whether domestic migration to the state will continue. Recent Census Bureau data suggest that New Hampshire’s domestic migration gain diminished between July 2023 and July 2024. Whether this represents a short-term fluctuation, or a long-term change remains to be seen. What our research clearly demonstrates is the critical role that migration plays in New Hampshire’s demographic and economic future.

Data

The U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS) produces annual aggregations of tax returns and exemptions (proxies of households and persons) that indicate whether the filer was in a different county from the prior year.1 These data were aggregated to reflect state-to-state migration. Because IRS data only apply to tax filers, the data do not cover the entire population, but the coverage is reasonably comprehensive. It tends to underestimate migration among younger adults just entering the labor force, the wealthiest, and poorest segments of the population. Even with these limitations, conclusions drawn from analysis of the IRS migration data are likely to be indicative of overall migration streams between states. Some IRS state migration data was obtained using the IRS Migration Profiles from the Missouri Census Data Center.2

About the Authors

- Kenneth M. Johnson is senior demographer at the Carsey School of Public Policy, professor of sociology at the University of New Hampshire, an Andrew Carnegie Fellow, and a researcher at the NH Agricultural Experiment Station. This research has been supported by the station through joint funding from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (under Hatch-Multistate project W-5001, award number 7003437) and the state of New Hampshire. The opinions are those of the authors and not those of the sponsoring organizations.

- Tyrus Parker is a research scientist at the Center for Social Policy in Practice at the Carsey School of Public Policy.

Endnotes

- U.S. Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income Division. SOI Tax Stats – Migration Data. Available from: https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-migration-data.

- Missouri Census Data Center (2025). IRS Migration Profiles [dataset application]. Available from: https://mcdc.missouri.edu/applications/irs-migration/.