download the brief

Key Findings

The number of nonmetropolitan counties with high poverty rates increased between the 2000 Decennial Census and 2011–2015 (hereafter 2013) American Community Survey (ACS), and so did the share of the rural population residing in these disadvantaged areas. Over this time period, the percentage of rural counties with poverty rates of 20 percent or more increased from a fifth to nearly one-third, and the share of the rural population living in these places nearly doubled to over 31 percent. Levels of concentrated poverty increased substantially both before and after the Great Recession in rural areas, while increases in urban areas occurred mainly during years affected by the economic downturn (Box 1). Increases in county-level poverty rates were also concentrated in rural areas with small cities, and the share of the population residing in high-poverty counties increased much more among the non-Hispanic white and black populations in rural areas than among the rural Hispanic population.

Understanding Poverty

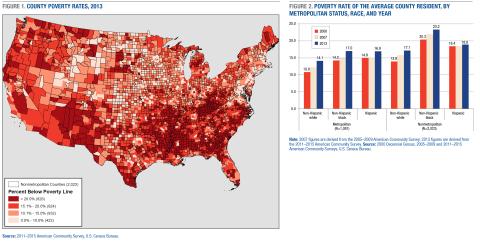

Poverty is unevenly distributed across the United States. Historically, rural areas have experienced greater levels of poverty than urban and suburban places. For example, in 2015, 16.7 percent of the population living in nonmetropolitan areas lived in families with incomes below the poverty line. In contrast, the poverty rate was 13.0 percent in metropolitan areas, and 10.8 percent among the subset of the metropolitan population living in suburban areas.1 However, considerable variation exists from place to place across both rural and urban America (Figure 1). Since 2000, spatially concentrated poverty has been on the upswing in the rural United States. The number of nonmetropolitan counties with high poverty rates increased substantially between 2000 and 2013, as has the share of the rural population residing in these disadvantaged areas. Over this thirteen-year period, the number of nonmetropolitan counties with poverty rates of 20 percent or more increased from 416 (20.6 percent of all nonmetropolitan counties) to 657 (32.5 percent of all nonmetropolitan counties), and the share of the rural population living in these places nearly doubled from 17.5 to 31.6 percent. Concentrated poverty also increased in metropolitan areas. In 2000, 72 metropolitan counties (6.7 percent of metropolitan counties) had poverty rates of 20 percent or more, yet by 2013 this figure had more than doubled to 169, or 15.6 percent of metropolitan counties. Likewise, the share of the metropolitan population residing in these high-poverty counties increased from 6.2 to 12.4 percent from 2000 to 2013. This nation-wide increase in concentrated poverty represents a stark reversal of what occurred during the 1990s, when declines in county poverty rates were substantial and widespread.2

There are a number of important patterns within these broad trends in county poverty rates. First, levels of concentrated poverty increased substantially in rural areas before the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009. From 2000 to 2007 (2005–2009 ACS), the share of the nonmetropolitan population living in counties with poverty rates above 20 percent increased by 5.8 percentage points—from 17.5 to 23.3—which was followed by a further increase of 8.3 percentage points between 2007 and 2013. In contrast, the share of the metropolitan population living in these high-poverty counties increased more after the recession (4.7 percentage points) than before (1.5 percentage points) it. While poverty in metropolitan areas appeared to be strongly associated with the Great Recession, the consistent increases in poverty rates among rural counties suggest that rural areas are facing a longer-term decline in economic conditions. In other words, the increasing concentration of poverty in rural America cannot be fully explained by the Great Recession and its aftermath, and therefore cannot be expected to be reversed as the post-recession recovery continues.

Second, the largest increases in concentrated poverty in the nonmetropolitan United States occurred in counties that include or are integrated with small cities of 10,000 to 49,999 residents, which are classified as micropolitan by the U.S. government. The percentage of these counties with poverty rates above 20 percent increased from 17.5 to 32.0 percent from 2000 to 2013, and the share of the micropolitan population residing in such high-poverty counties increased from 14.8 to 28.5 percent. Economic conditions in these micropolitan areas increasingly resemble the more isolated and sparsely populated rural counties that have historically been worst-off.3 The reasons for this convergence are not well understood, but the pattern we find suggests that rural poverty cannot be explained simply as a matter of spatial isolation or low population density.

Changes in concentrated poverty also varied among different racial and ethnic groups in rural areas (Figure 2). The shares of the non-Hispanic white and black populations living in high-poverty nonmetropolitan counties increased much more than for the Hispanic population. For example, the county poverty rate of the average non-Hispanic white and black resident in nonmetropolitan areas increased by 3.2 and 2.9 percentage points, respectively, between 2000 and 2013, compared to 0.4 percentage points for the average Hispanic resident of nonmetropolitan counties. In metropolitan counties, Hispanics experienced increases in exposure to concentrated poverty that were much more comparable to their non-Hispanic white and black metropolitan counterparts. The rural Hispanic population is seemingly experiencing unique economic circumstances. Our findings cannot explain why this is the case, but we note that the years in our study correspond to a period of increasing geographic dispersion of the Hispanic population to new, often rural destinations.4

The overall resurgence of concentrated poverty since 2000 should be of concern to policy makers and other stakeholders since areas with very high poverty rates face many social, economic, and health challenges. There is evidence that some of these challenges may stem from the effects of living in impoverished places, even among those whose families are not poor.5 Taking these and other findings into consideration, policy makers can use knowledge of where poverty rates are highest and increasing most rapidly to reform or develop new interventions they deem appropriate. Of course, our findings also showed that some rural places are characterized by very low poverty rates and fared relatively well over the years studied, even during one of the most severe macroeconomic downturns in U.S. history.6 When formulating policy, analysts and policy makers should therefore pay careful attention to variation in economic conditions, and their determinants, among rural counties and across the country as a whole.

Data

The data for this project are from county-level summary files of the 2000 U.S. Decennial Census, the 2005–2009 American Community Survey, and the 2011–2015 American Community Survey. We refer to the two American Community Survey samples by the mid-point of their time period for brevity. These data and corresponding geographic information were extracted from the National Historical Geographic Information System.7 The sample was restricted to the forty-eight contiguous states, and we constructed time consistent county-based units to account for a limited number of county boundary changes that took place between 2000 and 2015.

Box 1: Defining Rural & Urban

Definitions of rural and urban vary among researchers and the sources of data they use. Data for this brief were extracted at the county level, and counties were assigned a metropolitan status according to the 2003 Office of Management and Budget delineations. Metropolitan counties are defined to include (1) a central county (counties) containing at least one urbanized area with a population of at least 50,000 people, and (2) the counties that are socially and economically integrated with the urbanized area, as measured by commuting patterns. In this brief, the terms urban and metropolitan are used interchangeably, as are ruraland nonmetropolitan.

Endnotes

1. Bernadette D. Proctor, Jessica L. Semega, and Melissa A. Kollar, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2015, Current Population Reports, P60–256(RV) (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2016).

2. Daniel T. Lichter and Kenneth M. Johnson, “The Changing Spatial Concentration of America’s Rural Poor Population,” Rural Sociology, vol. 72, no. 3 (2007): 331–358.

3. Bruce Weber, Leif Jensen, Kathleen Miller, Jane Mosley, and Monica Fisher, “A Critical Review of Rural Poverty Literature: Is There Truly a Rural Effect?,” International Regional Science Review, vol. 28, no. 4 (2005): 381–414.

4. Daniel T. Lichter and Kenneth M. Johnson, “Immigrant Gateways and Hispanic Migration to New Destinations,” International Migration Review, vol. 43, no. 3 (2009): 496–518.

5. Robert J. Sampson, Jeffrey D. Morenoff, and Thomas Gannon-Rowley, “Assessing “Neighborhood Effects”: Social Processes and New Directions in Research,” Annual Review of Sociology, vol. 28, no. 1 (2002): 443–478.

6. Brian Thiede, Hyojung Kim, and Matthew Valasik,“The Spatial Concentration of America’s Rural Poor Population:

A Postrecession Update,” Rural Sociology, in press, doi: 10.1111/ruso.12166.

7. Minnesota Population Center, National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 11.0 [Database], Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2016, http://doi.org/10.18128/D050.V11.0.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Michele Dillon, Michael Ettlinger, Kenneth Johnson, Laurel Lloyd, Marybeth Mattingly, and Bianca Nicolosi at the Carsey School.