download the brief

Key Findings

Views on economic development vary from county to county. Less developed places see tourism and recreation, light manufacturing, independent small businesses, and forest-based industry as important to their future.

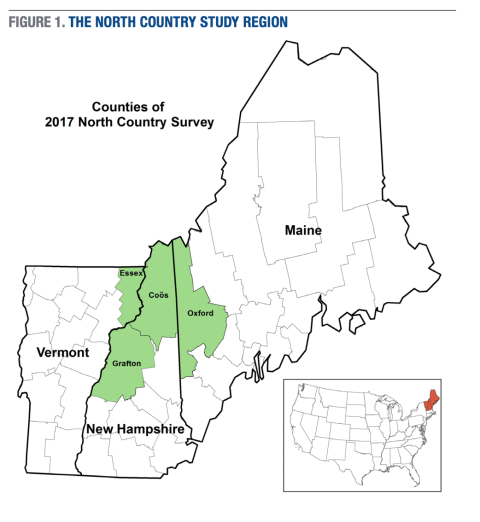

Hit hard by the national decline in natural-resource and manufacturing jobs, North Country communities in northern New Hampshire and bordering areas of Maine and Vermont (Figure 1) continue to face challenges in restructuring their economies.1 A 2008 study classified Coös County, New Hampshire, and Oxford County, Maine, as “amenity/decline” regions, a common pattern in rural America where historically resource-dependent places experience decline in their traditional industries, even while natural amenities present new opportunities for growth in areas such as tourism or amenity-based in-migration. Complicating this transition, there is often out-migration of young adults seeking jobs and financial stability elsewhere, as new industries in rural areas tend toward seasonal employment or require different kinds of skills.2 In this brief, we report on a 2017 survey that asked North Country residents about their perceptions, hopes, and concerns regarding this region. Many of the same questions had been asked on earlier surveys in 2007 and 2010, providing a unique comparative perspective on what has changed or stayed much the same.

The North Country Surveys

With support from the Neil and Louise Tillotson Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation, Carsey School researchers conducted a broad survey in summer of 2017. Interviewers from the University of New Hampshire Survey Center spoke by telephone with 1,650 randomly-selected residents in four North Country counties—Coös and Grafton, New Hampshire; Oxford, Maine; and Essex, Vermont.3 Many of the questions had also been asked in previous Carsey surveys done in 2007 (Coös and Oxford counties) and in 2010 (Coös, Oxford, and Essex counties).4 The ten-year span covered by these surveys, each contacting large and representative samples, provides a unique perspective on how views of people in this region have changed or stayed the same over the past decade.

Grafton County, New Hampshire, was not part of the earlier surveys, but was included in 2017 to widen the comparative perspective. This county—containing Dartmouth College and Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Plymouth State University, several high-tech industries, and tourism and ski resort developments— has seen more economic diversification and amenity-based growth than its North Country neighbors. The analyses that follow present two kinds of comparisons: first, among the four counties surveyed in 2017, where Grafton sometimes stands out; and, second, focusing only on Coös, tracked across three successive surveys in 2007, 2010, and 2017.

Important Problems

What problems affecting their communities do North Country residents see as most important? We asked them: For each of the following, please indicate if you think it is—or is not—an important problem facing your community today.

-

Lack of job opportunities

-

Substance abuse and overdoses

-

Manufacturing or sales of illegal drugs

-

Population declining as people move away

-

Poverty or homelessness

-

Declining property values

-

Not enough health and social services

-

Schools not as good as they should be

-

Lack of affordable housing

-

Violent or property crime

-

Lack of recreational opportunities

Figure 2 charts the percentage of Coös County respondents saying each problem is important on the 2007, 2010, and 2017 surveys.

Lack of job opportunities stands out as the top problem across all three surveys. An overwhelming 96 percent of respondents agreed this was important in 2010, in the wake of the 2008 Great Recession. This proportion declined significantly to 86 percent on the 2017 recent survey, an indication of improvement in people’s views of employment in the county, but the lack of jobs still ranked as the most important problem on our list.

Prior research and first-hand accounts establish that drug abuse and overdoses are formidable and growing problems in the North Country, as throughout all three states and elsewhere across the country. One study reported that the frequency of drug abuse among Coös County youth is higher than national levels, or than rural youth in general.5 In previous decades, drug problems here often meant illegal drugs or methamphetamine. More recently, opioid drugs including painkillers available by prescription have emerged as major problems. The perceived importance of manufacturing or sales of illegal drugs in Coös jumped from 55 percent in 2010 to 75 percent in 2017, with the sale of opioids likely in people’s minds as they responded. A new item we added in 2017 to reflect the opioid epidemic, substance abuse and overdose, ranked even higher: 80 percent of respondents said this is an important problem in their county.

Declining population as people move away is a fourth salient problem in Figure 2. On the post-recession survey in 2010, this reached its highest level at 72 percent, then slightly declined to 68 percent in 2017, still well above pre-recession levels. Concern about poverty or homelessness, and about health and social services, stand at lower levels but are slightly increasing. More encouraging signs are the significant declines in concern about school quality, affordable housing, and violent or property crime. Other sources indicate that Coös County has the lowest reported serious and violent crime rates in New Hampshire.6 A lack of recreational opportunities is cited by relatively few people in 2007 (14 percent) but had doubled by 2017. This might reflect changing ideas about recreation, rather than changing conditions in a region where outdoor activities remain close at hand. In each year women, young adults, and people with less education were more likely to see the lack of recreational opportunities as a problem. The rise in this perception from 2007 to 2010 occurred across all demographic groups, however.

Figure 3 draws a different set of comparisons using the same set of questions. These charts depict 2017 results only, but contrast Coös with the other three counties (so the Coös bars in Figure 3 are the same as the Coös 2017 bars in Figure 2).

Responses from more economically diverse and affluent Grafton County stand apart from the others on some items, as expected. Grafton residents are notably less likely to see lack of job opportunities, population decline, poverty or homelessness, declining property values, and violent or property crime as important problems. On the other hand, they express higher levels of concern about affordable housing, because Grafton’s amenity development and relative affluence has tended to raise prices. Responses from Oxford, Maine, and Essex, Vermont, tend to be closer to those of Coös on most items. Coös remains relatively high, however, on the perceived importance of substance abuse and drug problems. The lack of affordable housing is of least concern in Coös.

These survey response patterns partly reflect economic differences among counties. Grafton, for example, has the lowest unemployment rate— 2.3 percent, compared with 3.3 in Coös.7Oxford benefits from tourism and recreation connected to the White Mountains in New Hampshire, as well as its own lakes and natural areas, but has a 4.4 percent unemployment rate.8 Essex has the lowest median income and highest unemployment rate (5 percent) among these counties.9 Essex responses are similar to Coös regarding lack of job opportunities, population decline, and property value decline. Essex residents express the highest concern among this group about violent or property crime. Reported poverty rates in the four counties follow the same ordering as “poverty or homelessness” responses in Figure 3: Grafton has the lowest percentage of population below poverty (6.6 percent), followed by Coös (10 percent), Oxford (11.8 percent), and Essex (16.9 percent).

Economic Development

Figures 2 and 3 make clear the importance and problematic nature of North Country job opportunities. Looking toward the future, we asked residents:

Do you think each of the following forms of economic development are very important, somewhat important, or not important to your community’s future?

-

Tourism and recreation

-

Light manufacturing and a variety of new independent small businesses

-

Forest-based industries such as logging, pulp and paper, and lumber production

-

Wind-powered electricity generation

-

Wood-fired biomass electricity generation

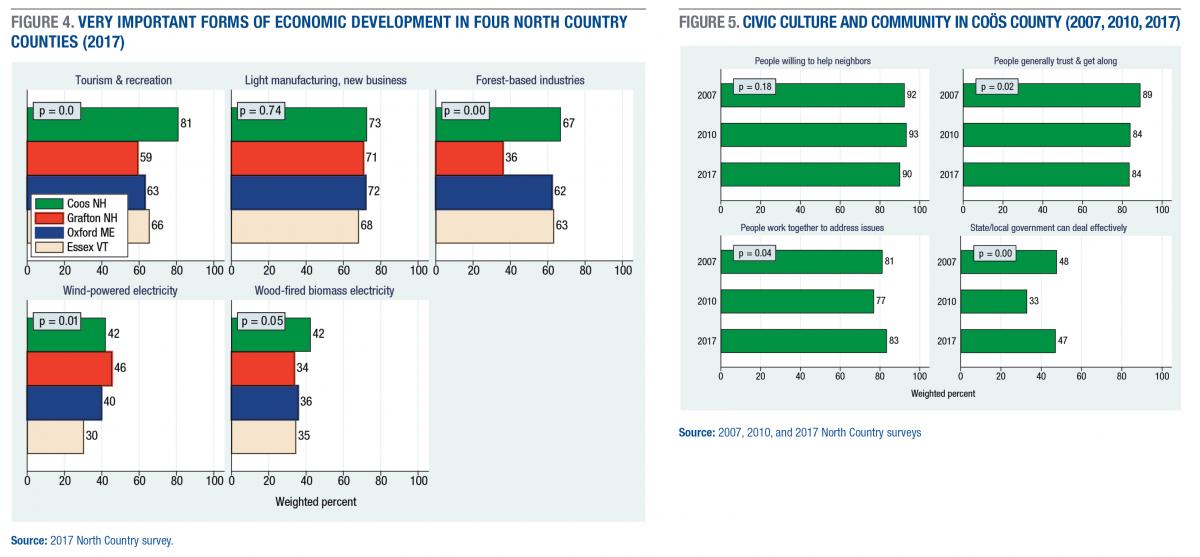

Figure 4 charts percentages saying each form of development is “very important,” comparing the four counties on the 2017 survey.

The North Country counties all are rural, amid forested landscapes. Essex, Coös, and Oxford have population densities from 9 to 28 people per square mile. Grafton, the most densely settled at 52 people per square mile, is still well below the New Hampshire average of 147 (or the United States as a whole, 91). Grafton also differs from the other three in having substantial income from non-resource, non-amenity employers such as the medical center, Dartmouth College, and some diverse industries. Grafton respondents, consequently, are least likely to consider future tourism, recreation, forest-based industries, or biomass development as very important to their community’s future. Conversely, they are most likely to prioritize wind-powered electricity, a relatively new industry in the North Country (and one opposed by many residents in Essex and Coös controversies10). Grafton’s low unemployment rate may also incline residents toward emphasizing resource conservation rather than resource use.11

In the other counties, forest industries have historically been major employers and are still seen as potential economic growth opportunities by residents. Coös County’s economic recovery has been slow following paper mill closures in the early 2000s, and the 2008 recession. But it was helped by tourism, including visitors from Canada, as well as a biomass plant that began full-power electricity production in 2014. Also, investments in economic development by the Neal and Louise Tillotson Fund and others have succeeded in strengthening the organizational capacity for future growth in the North Country, giving rise to some sense of optimism, but the region has yet to firmly establish a new trend of increasing numbers of jobs.

Civic Culture and Engagement

Figures 2 and 3 highlight North Country challenges, and Figure 4 shows hopes for economic development. What about community strengths, such as cooperation, trust, and civic culture? Responses to four questions asked on the 2007, 2010, and 2017 Coös surveys are charted in Figure 5.

Do you agree or disagree with the following statements about your community?

-

People around here are willing to help their neighbors.

-

People in this community generally trust one another and get along.

-

If faced with a local issue, people here could be counted on to work together.

-

State and local government have ability to deal effectively with important problems.

Coös residents overwhelmingly agree, with little change over the years, that people are willing to help their neighbors. Most also agree that people in their community generally trust one another and get along, although this proportion declined from 89 to 84 percent in recent surveys. On the other hand, the fraction agreeing that people could be counted on to address local issues rose from 77 percent in 2010 to 83 percent in 2017. Agreement that state and local government could deal effectively with local problems rose significantly as well (33 to 47 percent). In both cases, the lower 2010 values likely reflect lingering effects from the 2008 recession, which were largely overcome by 2017.

People express somewhat lower faith in government than in their fellow citizens, a pattern consistent with rural American values of individualism and community support.12 This might also reflect awareness that state and local government have limited power to deal with global competition and other large-scale forces affecting North Country life.

The civic culture and community questions depicted in Figure 5 have also been asked on other rural U.S. surveys. Figure 6 summarizes responses from one collection of surveys conducted from 2007 to 2011, in rural counties of four general types.13 Amenity rich places have growing economies and in-migration drawn by natural attractions. Economically declining areas formerly depended on natural resources and related manufacturing that no longer provide enough jobs; often their population is now shrinking. Chronically poor areas have a long history of rural poverty and underdevelopment that proves hard to escape. Amenity/decline areas tend to be transitional, with declining resource industries coexisting with potential for amenity growth. Coös County fits into this last group, as do Oxford and Essex Counties; Grafton County experienced both amenity growth and economic diversification, although its population has recently been stable.

The comparisons in Figure 6 are informal, because we are grouping many different counties together.14 Coös responses charted in Figure 5 are quite similar to the average for amenity/decline counties elsewhere with regard to helping neighbors, getting along, and working together. Coös respondents expressed somewhat less faith, however, in the effectiveness of their state and local governments.

Expectations for the Future

Given the problems, prospects, and strong appeal of North Country communities, how do people feel about their future in this region? Four questions assessed views on this topic.

-

Looking ahead, do you expect to continue living in this area for the next 5 years, or move somewhere else?

-

Do you think that 10 years from now, your community will be a better place to live, a worse place, or about the same?

-

Would you say that you and your family are better off financially, worse off, or about the same as you were 5 years ago?

-

If a young person moves away for opportunities elsewhere, would you hope that they return to work and raise a family in this community, or not?

In 2017, 80 percent of Coös respondents expected to live in this area for the next five years (in many cases, presumably longer). This proportion changed little over the past decade. Most also think their community will be a better place to live, or about the same, ten years from now. Assessments of family financial well-being dipped in 2010 following the recession, but since have rebounded well above previous levels for all demographic groups. The final panel in Figure 7 shows a similar rebound from 2010 to 2017 in the percentage saying they hope that young people who moved away will return to raise families in their community. (This question was suggested by local residents after the 2007 survey.) Overall, the responses in 2017 paint an encouraging picture of general optimism among Coös residents, and improvement since 2010.

Three of the four well-being questions shown in Figure 7 were also asked in eighteen other rural U.S. counties for the 2007 surveys. Compared with averages from other places, Coös respondents in 2007 and 2017 more often expected to continue living in the area for at least five more years. Coös residents also more often thought that their communities would be the same or better places to live in ten years. Although more optimistic about their communities, Coös residents were no more likely than others to think they or their families were financially better off, and had similar concerns about young people moving away.

This generally optimistic Coös picture recurs in the other North Country counties, as charted in Figure 8. Essex residents are somewhat more likely to plan on staying for at least five years, and Grafton residents are more likely to hope young people return—but in all counties these percentages are high. There are no significant differences among the counties in views of family economic well-being, or expectation that life there will be the same or better in the future.

Conclusion

Most people living in these North Country counties continue to be optimistic about their communities and their own situations. The profound economic transformation of this previously manufacturing-dominated region over the past several decades has not shaken this community confidence, but it does drive the ongoing concerns about job and economic growth opportunities. In her 1999 book, Worlds Apart, sociologist Mil Duncan looked at poverty in three rural communities: a coal mining town in eastern Kentucky, a farming community in the Mississippi Delta, and a mill town in New England’s North Country.15 In Duncan’s North Country town, there were fewer barriers to poor residents and broader public engagement in social activities and schools as the other residents than in the Kentucky and Mississippi towns. This fostered a sense that everyone belonged to the same community. In the 2014 edition of her book, Duncan notes North Country changes such as mill closing, amenity development, and an influx of housing-voucher recipients challenged such egalitarian traditions, while other developments such as biomass energy offered new hope to sustain it.16 Our North Country survey highlights a mix of this same strong sense of community and hopes for the future alongside frankly-perceived problems that both confirms and extends Duncan’s findings.

From a policy and regional economic assistance program perspective, focusing on programs to help existing businesses succeed, creating incentives to attract diverse businesses to the region, and training people to meet new workforce demands continue to make a great deal of sense. Successful transitions and community rebranding, for instance from a single large factory town to a diverse combination of businesses, require local support and engagement as well, despite the uncertain prospects of change.17 There is, however, the growing problem of substance abuse affecting all four counties as well as the states in which they are located. Attention needs to be paid so that the growing number of programs that emphasize education, treatment, and recovery support in all three states reach into these more rural and less populous regions and are not just concentrated in the larger population centers.

These social, economic and employment woes are not unique to the North Country, and in fact can be found in many of the rural areas of these three states and in other regions of the country as well. In some respects, the North Country’s rural, mountainous landscape offers potential advantages, not just for amenity development but lifestyle attractions that could draw other employers, or for renewable energy including wind power. There is room also for more advocacy at the state and federal levels for actions to launch and support programs specifically geared to address workforce, education, infrastructure, substance abuse, and other problems and issues affecting rural regions.

Endnotes

1. Martin Neil Baily and Barry P. Bosworth, “US Manufacturing: Understanding Its Past and Its Potential Future,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol 28(1) (2014): 3–26; Amy Glasmeier and Priscilla Salant, “Low-Skill Workers in Rural America Face Permanent Job Loss” (Durham, NH: Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire, 2006), http://scholars.unh.edu/carsey/6/.2006.

2. L.C. Hamilton, L.R. Hamilton, C.M. Duncan, and C.R. Colocousis, “Place Matters: Challenges and Opportunities in Four Rural Americas” (Durham, NH: Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire, 2008), http://scholars.unh.edu/carsey/41/.

3. Interviews took place from June 13 to July 24, 2017. Overall response rate is 19 percent. Probability weights are employed with all graphs and analysis in this brief, making minor adjustments for more representative results.

4. Hamilton et al., 2008; C.R. Colocousis, and J. Young, “Continuity and change in Coös County: Results from the 2010 North Country CERA survey,” (Durham, NH: Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire, 2011), http://scholars.unh.edu/carsey/143/; L.C. Hamilton, J. Hartter, T.G. Safford, and F.R. Stevens, “Rural environmental concern: Effects of position, partisanship and place,” Rural Sociology, 79(2) (2014): 257–281, doi: 10.1111/ruso.12023.

5. Karen T. Van Gundy, “Comparing teen substance use in northern New Hampshire to rural use nationwide” (Durham, NH: Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire, 2013), http://scholars.unh.edu/carsey/200/.

6. National Archive of Criminal Justice Data, “Uniform Crime Reporting Data Program,” Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, ISPCR Institute for Social Research, https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/

7. State Impact,“The Ultimate Guide to the North Country,” NPR, https://stateimpact.npr.org/new-hampshire/tag/north-country/; “2017 New Hampshire Local Area Unemployment Statistics,” New Hampshire Employment Security, Economic & Labor Market Information Bureau, Sept. 27, 2017, https://www.nhes.nh.gov/elmi/statistics/documents/laus-current.pdf.

8. Center for Workforce Research and Information,“Unemployment and Labor Force,” Maine Department of Labor, http://www.maine.gov/labor/cwri/laus.html.

9. United States Census Bureau, “QuickFacts: Essex County, Vermont; Oxford County, Maine; Coös County, New Hampshire; Grafton County, New Hampshire; New Hampshire” (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, 2016), https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/essexcountyvermont,oxfordco...

10. A. Pannebaker, “A dozen industrial wind farms under way in Vermont despite intense local opposition,” Vtdigger, May 24, 2012, https://vtdigger.org/2012/05/24/fourteen-industrial-wind-farms-planned-i... accessed 8/3/2017.

11. L.C. Hamilton, C.R. Colocousis, and C.M. Duncan, “Place effects on environmental views,” Rural Sociology, 75(2) (2010):326–347, doi: 10.111/j.1549-0831.2010.00013.x.

12. Hamilton et al., 2008.

13. The “four rural Americas” scheme was first outlined by Hamilton and coauthors in 2008, and applied to a set of 2007 surveys. A 2011 Carsey brief by Dillon and Young applied this scheme to an expanded set of surveys conducted through 2010, which we use here for Figure 6. M. Dillon and J. Young, “Community strength and economic challenge: Civic attitudes and community involvement in rural America” (Durham, NH: Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire, 2011), http://scholars.unh.edu/carsey/137.

14. For a list of the other counties involved, see Dillon and Young, 2011.

15. C.M. Duncan, Worlds Apart: Why Poverty Persists in Rural America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999).

16. C.M. Duncan, Worlds Apart: Poverty and Politics in Rural America, Second Edition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014).

17. M. Dillon, “Stretching ties: Social capital and the rebranding of Coös County, New Hampshire” (Durham, NH: Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire, 2011), http://scholars.unh.edu/carsey/149.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant to the Carsey School from the Neil and Louise Tillotson Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Tillotson Fund.