download the brief

Key Findings

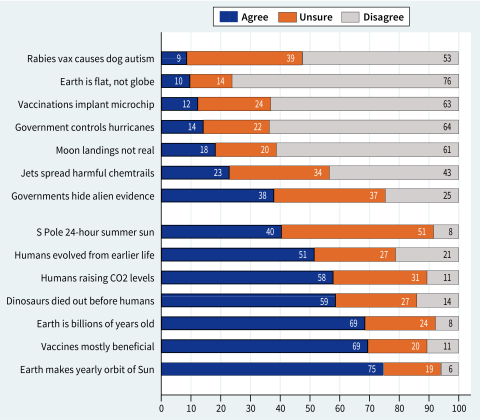

The nationwide POLES 2025 survey asked over 1,000 people whether they agreed with 14 statements that mixed conspiracy beliefs with basic scientific facts. Nine to 38 percent agreed with the conspiracies whereas 40 to 75 percent agreed with the science; many others were unsure.

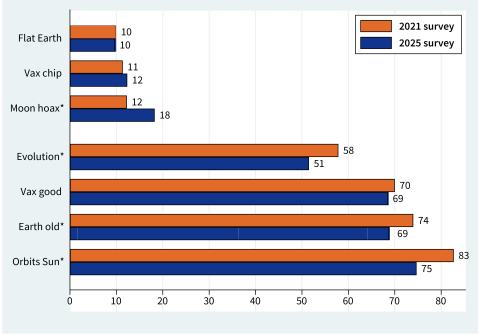

Comparing several items across surveys conducted in 2021 and 2025 suggests stability of some items but minor shifts in others—leaning toward greater support for conspiracies or less for science.

Younger generations were more likely than older to believe conspiracy statements.

Political identity correlates with conspiracism. Harris 2024 voters were least likely to agree with conspiracies. Trump voters, third-party voters, and nonvoters all were more likely to agree with these seemingly nonpartisan conspiracies.

Respondents who were likely to look up science-related information via social media or Artificial Intelligence (AI) programs inclined toward conspiracism. Conversely, those more likely to consult a search engine, Wikipedia, or science articles tended to agree with scientists.

The Carsey Perspectives series presents new ways of looking at issues affecting our society and the world. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsors or publisher.

Introduction

On the most recent nationwide Polar, Environment, and Science (POLES) survey in spring 2025, we asked over 1,000 people whether they agreed with fourteen statements that mixed conspiracy beliefs with basic scientific facts such as Earth orbiting the Sun. A minority of respondents, ranging from 9 to 38 percent, agreed with seven conspiracies on the survey, while larger fractions from 40 to 75 percent agreed with seven basic scientific statements. For both types, however, many people were unsure.

This brief explores POLES 2025 survey results to answer some questions and raise others:

- How do various conspiracy beliefs and science facts compare in terms of public acceptance?

- Do comparisons with an earlier POLES survey show signs of change?

- Who agrees with conspiracy claims, or with science?

- How do sources of information play into conspiracy beliefs or science knowledge?

- And, looking ahead, what do these findings suggest?

Conducting the 2025 POLES Survey

The first nationwide POLES survey was conducted via random- sample telephone interviews in 2016.1 It queried public knowledge of geography and natural science relating to Earth’s polar regions. Unsurprisingly, factual knowledge about polar regions proved to be limited, although some people appeared overconfident about their understanding.2

Some of the same polar-knowledge questions were asked again on a second POLES survey in 2021, this time using online methods (Qualtrics) to obtain a nationally representative sample. The growing prominence of science-related disinformation prompted the inclusion of several statements about conspiracy beliefs on this survey, alongside statements of basic scientific facts. Consistent with other studies, the 2021 survey found that conspiracism appealed to a small though not trivial minority of respondents.3

Evidence about conspiracism proved to be the most interesting aspect of the 2021 survey. A new survey described in this brief, POLES 2025, was designed as a follow-up to learn more about this topic. Its online sample (arranged through Qualtrics) was selected for national representativeness in terms of age, gender, race, education, and political party. Data collection took place in April and May. After an initial screening where we removed responses that were nonsensical, robot-like (e.g., blocks of questions “straight-lined” with yes or no answers), or completed too quickly, we retained a usable sample consisting of 1,134 U.S. adults.

The fourteen science and conspiracy items on the POLES 2025 survey are listed in Box 1. For example, respondents were asked whether they agree, are unsure, or disagree that NASA astronauts did not really land on the Moon and next, whether Earth is billions of years old. Conspiracy (C) and science (S) items were mixed together on the survey, providing researchers with a screening check for respondents who answered thoughtlessly—such as agreeing or disagreeing with everything. The seven science statements involve basic facts on which great majorities of the scientists in relevant fields agree. The seven conspiracy statements in contrast have no scientific support, and believers might explain that lack of support (or conversely the consensus support for science items) by asserting a hoax or conspiracy among scientists.

Box 1. Science and Conspiracy Items from the POLES 2025 Survey.

“S” or “C” (not shown in the survey itself) denote statements that are scientifically supported (S), or require belief that scientists are conspiring to hide the truth (C).

“Below is a list of science-related statements, some of which might be controversial. Read each statement carefully and indicate whether you agree, are unsure, or disagree.”

NASA astronauts did not really land on the Moon (C)

The Earth is billions of years old (S)

The Earth is flat, not shaped like a globe (C)

Humans evolved from earlier forms of life (S)

Vaccines have mostly been a benefit to human health (S)

Vaccinations against COVID implant microchips to track people (C)

The Earth makes a yearly orbit around the Sun (S)

Dinosaurs died out long before the first humans appeared (S)

Jet planes intentionally spread “chemtrails” of harmful chemicals (C)

Due to human activities, levels of CO2 in the atmosphere are now increasing (S)

Governments are hiding evidence about UFOs and alien visitors (C)

Government has the ability to control hurricanes (C)

When it is summer at the South Pole, the sun stays above the horizon for 24 hours a day (S)

Vaccination against rabies can cause autism in dogs (C)

Findings

Conspiracies and Science

Figure 1 charts responses re-ordered from lowest to highest percent of respondents who agree, which also sorts them into conspiracy and science categories. The first statement, rabies vaccination can cause autism in dogs, elicits the lowest level of agreement (9 percent) but also one of the highest levels of uncertainty (39 percent). There is no scientific basis for this claim, which is vaguely generalized from a false belief about human vaccines. Unlike other conspiracy statements on our survey, it has not been widely promoted online, but this lack of public discussion paradoxically might account for the high levels of uncertainty expressed. However, the idea has potentially serious implications. Growing pet-owner resistance to rabies vaccination has been reported by veterinarians, although rabies is fatal to humans and pets alike. An independent 2023 study with differently-worded questions found that 37 percent of general-public respondents thought rabies vaccine might cause autism in pets.4

Figure 1: Percent who agree and disagree with 14 conspiracy or science statements, ordered from lowest to highest agreement.

Note. Margins of error are roughly ±3 points; see Box 1 for question wording. Source: Polar, Environment, and Science Survey, 2025.

Among conspiracy belief statements, “governments are hiding evidence about UFOs and alien visitors” elicited the greatest agreement (38 percent) along with equal amounts of uncertainty (37 percent). By specifying “alien visitors,” the question’s wording meant to exclude a less radical view that unidentified aerial phenomena might be secret earthly aircraft, but some respondents could have answered with non-alien possibilities in mind.

Only 40 percent agreed that in summertime the South Pole experiences 24 hours of sunlight, making this simple geographic reality the most uncertain scientifically-valid statement. Although flat-Earth believers explicitly reject the existence of a South Pole and its midnight sun, many other respondents probably expressed uncertainty about this statement as a matter of knowledge, not conspiracy belief.5

At the other end of the figure, most respondents agree that Earth orbits the Sun. Even so, 25 percent disagree or are unsure about this basic fact—similar in magnitude to the 24 percent who agree or are unsure about whether the Earth is flat, which is commonly linked to claims that Earth does not orbit the Sun.

Comparisons with 2021 POLES Survey Results

Seven of the 14 science/conspiracy items in Figure 1 had been asked previously in 2021; Figure 2 compares these results. For three questions the 2021 and 2025 responses come within one point of each other, indicating no change. Four others, however, show statistically significant differences of five to eight points: Moon hoax, evolution, old Earth, and orbiting the Sun.6 Although the differences are small, they lean in similar directions—toward greater conspiracism or lower agreement with scientists.

Whether these differences between two surveys four years apart represent meaningful shifts in public opinion remains to be seen; future replications are needed. If confirmed, such changes would reinforce concerns that politics and social media are driving a rise in public conspiracism and turning away from science as a way of learning about the world.

Figure 2: Percent agreement with three conspiracy and four science items that were carried on both 2021 and 2025 surveys.

Note. Asterisks* indicate percentages showing statistically significant (p < 0.01) difference between surveys. Source: Polar, Environment, and Science Surveys, 2021–2025.

Generational and Political Divisions

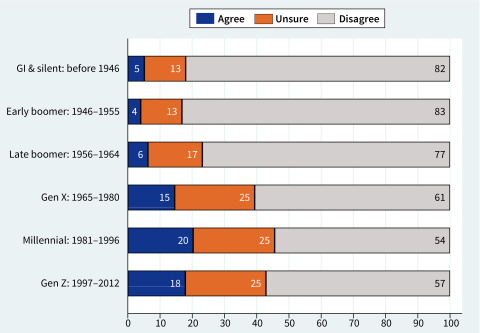

Generational differences and political divisions about who agrees with conspiracies and conversely who agrees with scientists stand out in the 2025 survey as they did in 2021. Figure 3 illustrates with 2025 generational divisions regarding, “Government has the ability to control hurricanes.” Only about 5 percent of respondents born before 1965 agree with this false statement, but agreement is at least three times higher among Generation X (born 1965–1980), Millennial (1981–1996), and Generation Z respondents (nominally 1997–2012, although no one born after 2007 was included in our survey). The fraction unsure whether hurricane control exists also roughly doubles among younger generations.

Similar generational differences occur with other conspiracy beliefs, most famously regarding claims that NASA’s Moon landings were a hoax. The openness of younger generations to Moon-hoax beliefs is commonly attributed to the fact that they were not born yet when the landings occurred, unlike older generations who lived through these exciting events.8 That explanation seems plausible regarding the Moon landings but does not fit other conspiracies such as hurricane control. To explain recurring generational differences, we need to consider additional factors such as sources of information.

Figure 3: Percent agree/disagree that government has the ability to control hurricanes, by respondent’s generation.7

Source: Polar, Environment, and Science Survey, 2025.

The hurricanes question also exhibits another pattern well established from previous research: conservatives tend to be more open to conspiracy beliefs about non-political as well as political topics.9 Figure 4 charts agreement among respondents who in 2024 voted for Trump, Harris, other candidates, or did not vote. Trump voters are almost three times more likely than Harris voters to believe the government can control hurricanes, and have a larger fraction that are unsure about this statement as well. Figure 4 adds a twist to this political story: nonvoters and third-party voters also are more receptive to conspiracy beliefs. Similar patterns—Harris voters least likely to agree, often by wide margins compared with Trump, other candidate, and nonvoters—occur across all seven of the conspiracy items on our survey.

Although claims that governments control hurricanes are false, such rumors can have real consequences. After Hurricane Helene struck the southeastern U.S. in September 2024, leaving more than 200 people dead, online conspiracists declared that the storm was “engineered” to get Kamala Harris elected, or perhaps to facilitate takeover of land for lithium mining. Meteorologists and emergency workers faced harassment and death threats from people who believed these claims; personnel in the field were turned away at gunpoint as they tried to help.10 Immediately after the deadly July 2025 flood in Texas hill country rumors began spreading online, amplified by political figures, that the floods resulted from deliberate weather manipulation. One Oklahoma TV station’s Doppler radar was vandalized, and a right-wing militia organization announced it would target others, asserting that the radars are used to “control the weather.”11 Similarly conspiratorial rumors followed other recent natural disasters, impeding response and recovery efforts—for example, after the September 2023 wildfire on Maui.12

Figure 4: Percent agree/disagree that government has the ability to control hurricanes, by vote in 2024 presidential election.

Source: Polar, Environment, and Science Survey, 2025.

Sources of Information

Online media play central roles in spreading conspiracy rumors, but they can spread helpful information as well by making facts and accurate explanations easier to look up. The 14 science/conspiracy items on our survey were followed by a set of questions asking what sources respondents were likely to check if they wanted to learn more about these topics (Box 2). Google and other search engines were by far the most common answer (64 percent), followed by scientific articles or books (50 percent) and Wikipedia (36 percent). Social media (26 percent) is at the bottom of the list, below artificial intelligence (28 percent) or friends and family (31 percent).

Box 2: Six information-source questions, re-ordered from most to least likely.

“If you wanted to learn more about one of the science-related topics above, would you be likely or unlikely to check with:”

Google, other search engines (64% likely, 27% might, 9% unlikely)

Scientific articles or books (50% likely, 31% might, 18% unlikely)

Wikipedia (36% likely, 37% might, 27% unlikely)

Friends or family (31% likely, 43% might, 26% unlikely)

Artificial intelligence programs like ChatGPT (28% likely, 33% might, 39% unlikely)

Social media (26% likely, 30% might, 44% unlikely)

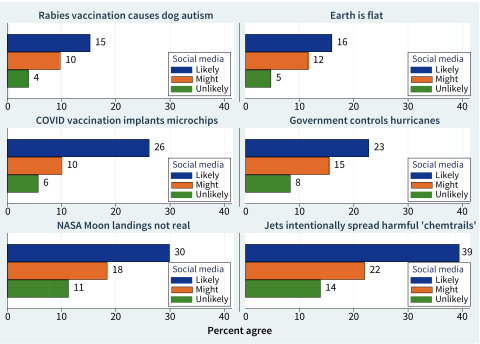

This ranking of search engines at the top and social media at the bottom appears differently if we analyze which sources correlate with which views. Agreement with scientifically supported statements was substantially higher among respondents who said they would consult a search engine, science book/article, or Wikipedia for information on science-related topics. Agreement with conspiracy statements, on the other hand, tended to be lower among people consulting these sources. Conspiracy believers were more likely to consult social media or artificial intelligence (AI) programs such as ChatGPT for science-related information. Figure 5 charts social media patterns for six conspiracy beliefs. Social-media consulting respondents were around three times more likely to agree with each of these six conspiracy statements. A similar pattern, although not as strong, occurs regarding AI programs like ChatGPT: people who consult AI for science information more often hold conspiracy beliefs.

Further statistical analysis beyond the scope of this brief confirms that the correlation between conspiracy beliefs and social media reliance is not due to differences in respondent age, education, political views, or other characteristics.13 This correlation reflects complex interacting dynamics. People who are more inclined to look up science topics on social media will often come across sensational conspiracy claims (often promoted from monetized or agenda-driven accounts). If they click on those claims, algorithms designed to maximize engagement will suggest more items of similar types. For example, watching one video about government-controlled hurricanes could be followed by links to the next and the next, and so on. The “social” aspect of social media also connects people with others, perhaps geographically scattered, who share and encourage their beliefs and feelings of special knowledge. Purposefully addictive social media features can draw some individuals “down the rabbit hole” where conspiracy beliefs define their reality, isolated from contrary information.14

Figure 5: Percent agree with six conspiracies, by how likely respondent is to check social media for information about science-related topics.

Source: Polar, Environment, and Science Survey, 2025.

Countering Conspiracism

Generational differences, social- media effects, and our tentative comparison between two surveys point toward conspiracism becoming an increased part of public life. The rapid development of artificial intelligence technologies that can realistically simulate any person, speech, or imaginary event will magnify the power of conspiracy claims.

As Internet use grows worldwide, leading social media platforms have scaled back or abandoned responsibility for fact-checking. Attempting to counter the resulting flood, other sources offer advice on judging whether new information you encounter might really be misinformation (wrong) or disinformation (intentionally misleading).15 The rapid spread of artificial intelligence presents further challenges, as such software (now also incorporated into many search engines) may offer seemingly authoritative but made-up claims supported by imaginary citations. In a new application of an old word, such AI-produced falsehoods are termed “hallucinations.”

As individuals we have opportunities to speak out with friends and family, or through online forums, casual encounters, and other speech or writing.16 Even if it is difficult to persuade conspiracy believers, it is important to actively counter conspiracy claims to inform neutral onlookers and not leave the impression that unfounded claims stand unopposed.

Conducting our own research and encouraging others to do so can help us to be more informed. For example, a quick search reveals that not just a few but hundreds of thousands of photos exist of globe Earth, with different countries’ space agencies adding more every day. Or that NASA’s Moon landings are confirmed by many independent sources including photographs sent back by Japanese, Indian, Chinese, and South Korean spacecraft.17 Moreover, for such conspiracies to be real would implausibly require secret participation by vast numbers of people and cooperation from all relevant experts in all countries across time scales from years to centuries or millennia.

Broader progress against conspiracism calls for enacting public policy measures that encourage robust media fact-checking, and laws against presenting AI fabrications as real. But here we meet the elephant in the room. The most consequential and prevalent conspiracy beliefs in the United States today are not the ones asked about in our survey, but others promoted by political media and leaders advancing their own agendas.18 And in political realms, who defines what is false information? Across the contemporary U.S. political landscape, proposals against spreading disinformation face powerful resistance. Other nations face disinformation challenges of their own, sometimes influenced by U.S. politics and media.19 From international experience might come workable policies that point the way forward.

Endnotes

- Hamilton, L.C. 2016. “Where is the North Pole? An election-year survey on global change.” Durham, NH: Carsey School of Public Policy. https://dx.doi.org/10.34051/p/2020.274

- Hamilton, L.C. 2018. “Self-assessed understanding of climate change.” Climatic Change 151(2): 349–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2305-0

- Hamilton, L.C. 2022. “Conspiracy vs. science: A survey of U.S. public beliefs.” Durham, NH: Carsey School of Public Policy. https://dx.doi.org/10.34051/p/2022.08

- Motta, M., G. Motta & D. Stecula. 2023. “Sick as a dog? The prevalence, politicization, and health policy consequences of canine vaccine hesitancy (CVH).” Vaccine 41: 5946–5950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.08.059 PMID: 37640567

- McRae, M. 2024. “Flat Earthers went to Antarctica to look at the Sun. Here’s what happened.” Science Alert 12/20/2023, retrieved 6/13/2025. https://www.sciencealert.com/flat-earthers-went-to-antarctica-to-look-at-the-sun-heres-what-happened

- Agreement percentages are significantly different (p < .01) comparing 2021 and 2025 responses to the Moon hoax, evolution, old Earth, and orbits Sun items, as established by simple chi-square tests. Moreover, these between-survey differences also remain significant (p < .01) in logistic regression models that control for respondents’ generation and political views.

- The “early vs. late boomer” distinction follows demographic research such as:

Zheng, H., J. Dirlam, Y. Choi & L. George. 2023. “Understanding the health decline of Americans in boomers to millennials.” Social Science & Medicine 337: 116282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.116282 - Dean, S. 2018. “No, one-third of Millennials don’t actually think Earth is flat.” Science Alert (April 4, 2018), retrieved 6/13/2025. https://www.sciencealert.com/one-third-millennials-believe-flat-earth-conspiracy-statistics-yougov-debunk

Hamilton 2022, note 3.

Newport, F. 1999. “Landing a man on the Moon: The public’s view.” Gallup News Service (July 20), retrieved 6/13/2025. https://news.gallup.com/poll/3712/Landing-Man-Moon-Publics-View.aspx - Many studies have noted political dimensions underlying conspiracy beliefs and science rejection. For example:

Goldberg, Z.J. & S. Richey S. 2020. “Anti-vaccination beliefs and unrelated conspiracy theories.” World Affairs https://doi.org/10.1177/0043820020920554

Hamilton, L.C. 2024. “Trumpism, climate and COVID: Social bases of the new science rejection.” PLoS One 19(1): e0293059. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293059

Hofstadter R. 1964. “The paranoid style in American politics.” Harper’s Magazine November: 77–86, retrieved 6/13/2025. https://faculty.washington.edu/jwilker/353/Hofstadter.pdf

Lewandowsky, S., G.E. Gignac & K. Oberauer K. 2013. “The role of conspiracist ideation and worldviews in predicting rejection of science.” PLoS One 8(10): e75637. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0075637 PMID: 24098391

Mann M. & Schleifer C. 2020. “Love the science, hate the scientists: Conservative identity protects belief in science and undermines trust in scientists.” Social Forces 99(1): 305–32. https://doi.org/doi:10.1093/sf/soz156

Van der Linden, A., C. Panagopoulos, F. Azevedo & J.T. Jost. 2020. “The paranoid style in American politics revisited: An ideological asymmetry in conspiratorial thinking.” Political Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.126810162-895X42(1) - Leopold, J. 2024. “Chilling disinformation threats were aimed at FEMA workers, documents show.” Bloomberg 10/25/2024, retrieved 6/13/2025. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2024-10-25/documents-show-chilling-threats-to-fema-workers

Spring, M. 2024. “How hurricane conspiracy theories took over social media.” BBC 10/10/2024, retrieved 6/13/2025. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c1e8q50y3v7o - Huang, P. & H. Jingnan. 2023. “How rumors and conspiracy theories got in the way of Maui’s fire recovery.” National Public Radio 9/28/2023, retrieved 6/13/2025. https://www.npr.org/2023/09/28/1202110410/how-rumors-and-conspiracy-theories-got-in-the-way-of-mauis-fire-recovery

- Burris, S.K. 2025. “Militia fueled by bizarre conspiracy theory brings down weather radars.” Raw Story July 9. https://www.rawstory.com/anti-government-militia/

- Multivariate statistical analyses not shown here confirm that agreement with all seven conspiracy belief is significantly higher among respondents who say they are likely to consult social media, even if we control for respondent characteristics including age, gender, race, income, education, religion, and political identity.

- Examples:

Dominik A. Stecula, D.A. & M. Pickup. 2021. “Social media, cognitive reflection, and conspiracy beliefs.” Frontiers in Political Science. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.647957

Enders, A.M., J.E. Uscinski, M.I. Seelig, et al. 2024. “The relationship between social media use and beliefs in conspiracy theories and misinformation.” Political Behavior 45:781–804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09734-6

Xiao, X., P. Borah & Y. Su. 2021. “The dangers of blind trust: Examining the interplay among social media news use, misinformation identification, and news trust on conspiracy beliefs.” Public Understanding of Science 30(8): 977–992. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662521998025 - Examples:

Canadian Centre for Cyber Security. 2024. “How to identify misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation (ITSAP.00.300).” Government of Canada, May. Accessed 6/28/2025. https://www.cyber.gc.ca/en/guidance/how-identify-misinformation-disinformation-and-malinformation-itsap00300

Jennings Library. 2025. “Disinformation and misinformation.” Caldwell University, January 10, accessed 6/28/2025. https://libguides.caldwell.edu/disinformation/identify

Parks, M. & S. Douglis. 2019. “Fake news: How to spot misinformation.” National Public Radio, October 31. Accessed 6/28/2025. https://www.npr.org/2019/10/29/774541010/fake-news-is-scary-heres-how-to-spot-misinformation

Sinclair, H.C. 2020. “10 ways to spot online misinformation.” The Conversation September 17, accessed 6/28/2025. https://theconversation.com/10-ways-to-spot-online-misinformation-132246 - Examples:

Pappas, S. 2023. “Conspiracy theories can be undermined with these strategies, new analysis shows.” Scientific American April 5, retrieved 6/13/2025. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-can-you-fight-conspiracy-theories/

O’Mahony, C., M. Brassil, G. Murphy & C. Linehan. 2023. “The efficacy of interventions in reducing belief in conspiracy theories: A systematic review.” PLoS ONE 18(4): e0280902. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280902

Manke, K. 2025. “Why conspiracies are so popular—and what we can do to stop them.” UC Berkeley Research February 5, accessed 6/13/2025. https://vcresearch.berkeley.edu/news/why-conspiracies-are-so-popular-and-what-we-can-do-stop-them - Wikipedia. “Third-party evidence for Apollo Moon landings.” Retrieved 6/13/2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Third-party_evidence_for_Apollo_Moon_landings

- Examples:

Evanega, S., M. Lynas, J. Adams & K. Smolenyak. 2020. “Coronavirus misinformation: Quantifying sources and themes in the COVID-19 ‘infodemic’.” Alliance for Science, retrieved 6/13/2025.

https://allianceforscience.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Evanega-et-al-Coronavirus-misinformationFINAL.pdf - Bateman, J. & D. Jackson. 2024. “Countering disinformation effectively: An evidence-based policy guide.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, accessed 6/14/2025. https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/01/countering-disinformation-effectively-an-evidence-based-policy-guide?lang=en

Funke, D. & D Famini. 2019. “A guide to anti-misinformation actions around the world.” Poynter, accessed 6/13/2025. https://www.poynter.org/ifcn/anti-misinformation-actions/

About the Author

Lawrence C. Hamilton is senior fellow at the Carsey School of Public Policy and adjunct research professor at the University of New Hampshire. UNH supported the POLES 2025 survey; the earlier POLES 2021 survey was supported by grants from the U.S. National Science Foundation (OPP-1748325 and OPP-1822424).

© 2025. University of New Hampshire. All rights reserved.