Key Findings

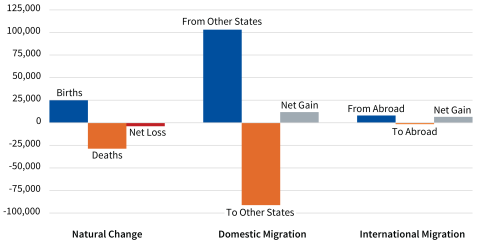

New Hampshire’s demographic future depends heavily on migration. The state’s population continued to grow in 2021 and 2022 because a migration gain of 18,300 was enough to offset the excess of deaths over births. More people died (28,700) than were born (24,900) in New Hampshire in the past two years. Covid certainly contributed to this loss, but annual deaths already exceeded births in the state for several years before the pandemic. The state’s net migration gain is the result of a significant flow of 204,000 people into and out of the state. More than 111,000 people moved to New Hampshire during the period compared to 93,000 who left the state (Figure 1). Most of this migration gain was people moving to New Hampshire from other states, but there was also a significant migration gain from abroad.

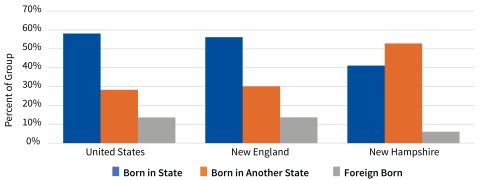

Most of New Hampshire’s Population Is From Somewhere Else

Recently released Census data underscore the mobility of New Hampshire’s population and provide insights into the origins of the migrants to the state. Only 41 percent of the state’s residents were born in New Hampshire (Figure 2). The majority (53 percent) were born elsewhere in the United States and then migrated to New Hampshire. In contrast, most of the population in the nation and in New England reside in the state in which they were born. New Hampshire also has far fewer foreign-born residents than either New England or the country.

Figure 1. Demographic Change in New Hampshire, 2021 and 2022

Analysis: K.M. Johnson, Carsey School, University of New Hampshire. Source: 2021 and 2022 ACS from U.S. Census Bureau. 2021 and 2022 provisional estimates of births and deaths from NCHS-CDC.

Figure 2. Place of Birth for Residents of United States, New England, and New Hampshire, 2017 to 2021

Analysis: K.M. Johnson, Carsey School, University of New Hampshire. Source: 2017 to 2021 ACS from U.S. Census Bureau.

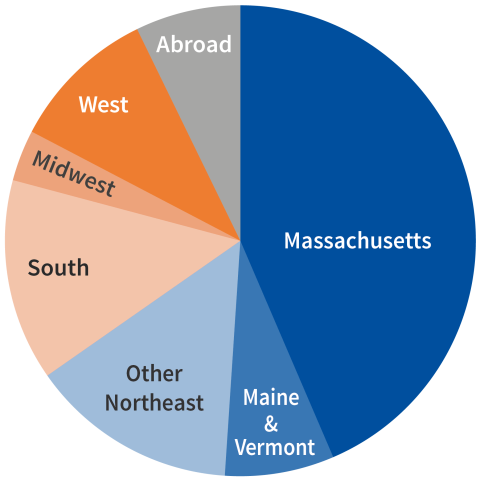

Massachusetts has long been the largest source of migrants to New Hampshire. More than 25 percent of New Hampshire residents were born in Massachusetts. Recent data suggest this trend is continuing. Nearly 44 percent of the migrants to the state in 2021 and 2022 came from Massachusetts (Figure 3). Neighboring Maine and Vermont together provided an additional 8 percent of recent migrants. The state also received significant numbers of migrants from elsewhere in the Northeast (14 percent), and from the South (14 percent), as well as modest shares from the West (10 percent) and Midwest (3 percent). Migrants from abroad accounted for 7 percent of recent arrivals in the state.

Migration Is Critical to New Hampshire’s Future

Traditionally, New Hampshire has grown both because of migration gains and because of a surplus of births over deaths. That is no longer the case. Deaths have exceeded births in each of the last six years, predating the onset of the Covid pandemic. This natural loss is the result of the state’s aging population, and of low fertility among the diminishing share of women in their child-bearing years. With more deaths and fewer births, migration is critical to the state’s future, but it is important to recognize that migration gains depend not only on how many people move in, but also on how many people do not migrate out. The latter population far outweighs the number of movers: nearly 1.2 million New Hampshire residents who resided in the state two years ago did not migrate. Attracting migrants and retaining residents have important implications for the state’s future population, labor force, and economy—as well as for the people, communities, and organizations that make New Hampshire a desirable place to live, work, and raise families. Understanding why residents come to New Hampshire, why they leave, and why so many decide to continue to live here is important to the state’s future and should be part of a comprehensive development strategy.

Figure 3. Migrants to New Hampshire in 2021 and 2022

Analysis: K.M. Johnson, Carsey School, University of New Hampshire. Source: 2021 and 2022 ACS from U.S. Census Bureau.

Data

Migration data for this study come from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) of 2022, 2021, and 2017–2021. Fertility and mortality data are from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The migration estimates derived from the ACS should be interpreted with caution. Although ACS data are comprehensive, they are based on samples and thus are subject to sampling error. Some of the NCHS birth and death data are provisional and subject to revision.

Kenneth M. Johnson is senior demographer at the Carsey School of Public Policy, professor of sociology at the University of New Hampshire, and an Andrew Carnegie Fellow. His research was supported by the NH Agricultural Experiment Station through joint funding from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (under Hatch-Multistate project W5001, award number 7003437) and the state of New Hampshire. The opinions are his and not those of the sponsoring organizations.