Key Findings

The Carsey Perspectives series presents new ways of looking at issues affecting our society and the world. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsors or publisher.

Working from home, once a rare feature of office culture, became common during the COVID-19 pandemic, and as infections fall and rise it seems likely to persist and even become standard procedure. But in the top-down American office, where facetime with your manager or the chief can make the difference between thriving or languishing, can working from home work against you? And if so, are Black professionals, who already experience discrimination in pay and promotion in the American workplace, at special risk?

A 2015 study of a Chinese call center sheds light on the first question. Those working from home experienced a 13 percent increase in performance. Yet the promotion rate conditional on this performance fell. “One story that is consistent with this,” the authors write, “is that home-based employees are ‘out of sight, out of mind.’”1

To gain insight into the second question, we surveyed members of a Black professional staff organization and networking group based in the Greater Washington Metropolitan area.2 Our purpose was to obtain their perspectives on working from home and the impact that the death of the office could have on Black professionals’ advancement.

Black Workers, the Pandemic, and What Offices Have to Offer

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on Black Americans. A disproportionate number of deaths have occurred in Black communities,3 and Black workers have been especially likely to become jobless. A recent survey of 40,000 workers4 found that even Black workers who remained working experienced higher rates of burnout and depression compared to other groups, making them more vulnerable to virtual isolation while working from home.5

Working from home 100 percent of the time may disproportionately impact the professional development and mentoring opportunities of Black professionals in America. Historically, offices have facilitated professional opportunities for Black Americans by providing a shared space where people of all races are required to interact with one another. And being mentored virtually is not like being mentored in person: effective work relationships have traditionally relied on interactions at close proximity and in-person. In general, what helps professionals, particularly those who are Black, thrive in the office space are the water-cooler conversations about the game last night, drop-by’s to talk about office issues, and all the unplanned work and nonwork conversations that play a major role in the formation of relationships. All of these are less likely to occur during scheduled meetings that are virtual.

Because Black people are more likely to face marginalization, working from home is especially challenging. Blacks are less likely to be in leadership or management roles, meaning that visibility to senior colleagues may be especially critical for Black professionals. Together, there is a serious risk that the loss of the traditional office would disproportionally leave Black professionals behind. In the 2019 survey “Being Black in Corporate America,” Black professionals were more likely to encounter racial prejudice and micro-aggressions than any other racial or ethnic group.6 By unveiling the obstacles to equity that currently exist in access to health care, employment, and social services, COVID-19 has provided a literal life-or-death demonstration of how discriminatory actions show up in the workplace and in society.

A recent article in the Harvard Business Review7 highlighted how Blacks in the workforce still face greater obstacles to advancement compared to their white counterparts. Even after the Civil Rights Act and a slew of diversity and inclusion initiatives in the workplace, Black Americans’ progress toward leadership roles and greater economic well-being remains slow. Black workers feel less supported in their jobs than their non-Black peers do, and Black managers report receiving less psychosocial support than their white counterparts. Further eroding this support and engagement through the loss of office-based interaction could have an especially consequential impact on Black Americans, yet few articles have been written on this topic.

Findings of the Survey

While our sample is small and we cannot make sweeping generalizations, we present here what we’ve learned from our online survey of Black professionals in the Congressional Black Associates network group. The respondents had a variety of opinions about remote work and the impact of working from home. As shown in Figure 1, most respondents (10 of 13) support working from home full time. But despite this support, most see challenges associated with fully remote work. For instance, most participants (8 of 13) feel that the death of the traditional office could create further disparities for Black professionals in an already unlevel playing field. Most participants (9 of 13) also feel that remote work environments will create fewer opportunities to engage in collaborative interactions with colleagues to build meaningful relationships.

Figure 1. Share of Surveyed Black Professionals Who Agree with the Following (n=13)

As is surely true for many professionals, professionals are judged by the quality of their surroundings while using remote meeting technology platforms such as Zoom or Webex. However, this is especially important here as one’s confidence about their surroundings could be proportional to the financial resources one has to create a quality work environment. Therefore, if workers feel self-conscious it may be because they are less resourced than their colleagues, which may also be an indicator of a less effective work-from-home environment. White young professionals are more likely to have higher incomes compared with Black professionals. Most participants (10 of 13) believe that 100 percent remote work will create a more classist society, while a smaller majority (7 of 13) believe that it would create a more racially divided society.

In addition to single-choice survey responses, participants offered further insight through open-ended qualitative responses. Qualitative survey responses included discussions of systemic racism and barriers Black professionals face, the uncertainty that remote versus in-office work makes any difference, and the benefits and drawbacks of working from home depending on the situation. One participant stated that not everyone has a good environment in which to work from home. Another felt that Black professionals need face-to-face interactions in order to advance in their careers.

Discussion

Though most Black professionals in our survey support working from home, many also think that historically offices have provided Black professionals with opportunities for information and relationships and that the death of the traditional office could create further disparities, particularly in job promotions and pay, for Black professionals in an already unlevel playing field. Further, Black professionals are more vulnerable than whites to having social distancing lead to professional isolation, which will likely impact their ability to receive promotions. Working from home could also impact the mentoring and professional opportunities of Black professionals. These Black professionals appear to appreciate, along with their non-Black colleagues, the convenience and safety of working from home but harbor concerns about the impact on Black professionals’ career advancement. Offices have enhanced financial and professional opportunities for Black Americans by providing the rare, shared space where people of all races are not only required to interact with one another but are required to interact by law in a civil and respectful manner.

As an already racially segregated society becomes more politically and economically fragmented, the office holds a place in bringing people together to work toward common goals. The uncertainty over the future of offices is concerning. Although people have become accustomed to working from home, it’s likely that offices are not dead—instead, they are being reconfigured into hybrid models with options for employees to work some days from home and other days in the office. Therefore, it is still important to preserve the physical office space. The pandemic is shining a new light on the importance of diversity, equity, and inclusion. It is imperative that companies give equal footing to their employees by giving them a seat at the table. It’s also imperative that employers are aware that Black professionals are more likely to experience micro-aggressions, burnout, and depression, and that it is important to prioritize their mental health. In short, to help ensure that working from home does not unlevel the playing field for Black professionals, they need to feel a sense of belonging and that they are valued.

A huge benefit of the traditional office space is that it has historically served Black professionals as a means to develop relationships, gather information, and create opportunities for advancement that are significantly more challenging to provide virtually. Therefore, companies should be encouraged to put return-to-work safety plans in motion and encourage their employees to get vaccinated. However, the COVID-19 vaccination uptake rate is lower among the Black population, in part linked to the justified mistrust some feel toward medical establishments. In addition, accessing adequate childcare may be more of an issue for Black professionals than whites because childcare was disproportionately lacking in Black and Latinx neighborhoods pre-pandemic.8 While employers may have justifiable concerns about the resurgence of the COVID-19 virus when offices fully resume their operations, COVID-19 safety can be addressed by utilizing technology advancements such as ultraviolet lighting, disinfectant sprays, touch-free door entry and elevator systems, and antibacterial metallic high-touch surfaces; high-quality ventilation; and physical distancing

Data and Methods

This survey was conducted between April 19 and May 15, 2021, online via the Qualtrics survey tool among the Congressional Black Associates (CBA), of which author John Jones is a former member. We identified the CBA as a convenience sample comprising of young Black professionals who intersect with public policy. John received approval for the survey from an executive representative of the CBA, and 200 participants were invited from a private list of members; no incentive was offered. Specific survey respondents were anonymous and no individually identifying information was collected. This survey was approved by the UNH Institutional Research Board, UNH IRB #8485.

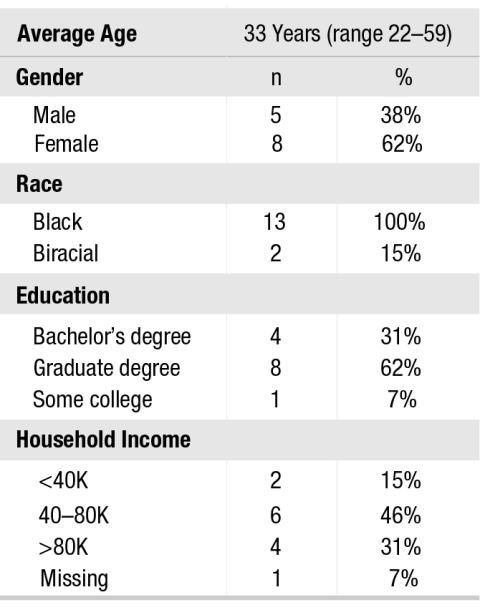

The average age of the respondents was 33 years (Table 1). Most (9 of 13) were between the ages of 27 and 36—generally millennial professionals in the early part of their careers. Education levels are high: almost two-thirds have graduate degrees. Household income ranged from less than $40,000 to over $80,000 per year. A majority of the participants were female. ADA Table

|

Average age |

33 years (range 22-59) |

|

|

Gender |

n |

% |

|

Male |

5 |

38% |

|

Female |

8 |

62% |

|

Race |

||

|

Black |

13 |

100% |

|

Biracial |

2 |

15% |

|

Education |

||

|

Bachelor's Degree |

4 |

31% |

|

Graduate Degree |

8 |

62% |

|

Some College |

1 |

7% |

|

Household Income |

||

|

<40K |

2 |

15% |

|

40-80K |

6 |

46% |

|

>80K |

4 |

31% |

|

Missing |

1 |

7% |

Table 1. Respondent Demographics (n=13)

Endnotes

- Nicholas A. Bloom, James Liang, John Roberts, and Zhichun Jenny Ying, “Does Working From Home Work? Evidence From a Chinese Experiment,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 130, no. 1 (February 2015): 165–218, https://nbloom.people.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj4746/f/wfh.pdf; cited in Sarah Kessler, “Will Remote Workers Get Left Behind in the Hybrid Office?” New York Times, August 5, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/05/business/dealbook/remote-work-bias.html?searchResultPosition=1.

- Congressional Black Associates, “Our Story,” congressionalblackassociates.com.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),“Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death by Race/Ethnicity” (Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2021), https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html.

- Economic Policy Institute (EPI), “2020Q3-Q4: State Unemployment by Race and Ethnicity” (Washington, DC: EPI, 2021), https://www.epi.org/indicators/state-unemployment-race-ethnicity-2020q3q4/.

- K. Butler, “Companies Battle Worker Burnout to Meet Diversity Pledges,” Bloomberg.com, May 18, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-05-18/how-companies-are-dealing-with-black-worker-burnout-during-covid-pandemic.

- Center for Talent Innovation, “Being Black in Corporate America: An Intersectional Exploration,” Coequal.org, 2019, https://coqual.org/reports/being-black-in-corporate-america-an-intersectional-exploration.

- L.M. Roberts and A.J. Mayo, “Toward a Racially Just Workplace,” Harvard Business Review, November 14, 2019, https://hbr.org/2019/11/toward-a-racially-just-workplace.

- Novoa, C. “How Child Care Disruptions Hurt Parents of Color Most,” (2020, June 29). Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/early-childhood/news/2020/06/29/486977/child-care-disruptions-hurt-parents-color/.

About the Authors

- John Jones focuses on the intersection of real estate and technology and serves as a senior vice president with a real-estate trade association in Washington D.C.

- Jordan Hensley is a policy analyst at the Carsey School of Public Policy.