Key Findings

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to upend the lives of U.S. families with children. The abrupt closure of schools and childcare centers at the start of the pandemic was widespread, but childcare challenges for working families are hardly new. Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen recently described childcare as a “broken market,”1 partly in recognition that the pandemic has further constricted already-limited childcare supply and further disincentivized its already-underpaid workforce. Just as the pre-existing problems in the childcare system were not equally shared, with women, low-income people, and people of color bearing the greatest burdens, childcare’s ongoing challenges are not evenly distributed either.2

Using data from the late summer through the fall of 2021, this brief documents recent racial and income disparities in reports of inadequate access to childcare and identifies the employment-related consequences of these shortages. This is the first in a series of research briefs that will focus on disparities in childcare access during the COVID-19 pandemic.3

In Fall 2021, about 5 million households had a child under age 12 who was unable to attend childcare as a result of the provider being closed, unavailable, unaffordable, or because of safety concerns in the past four weeks.4 This represents one-quarter (23.6 percent) of households with children in this age group nationwide who responded to a question about childcare in a recent Household Pulse survey.

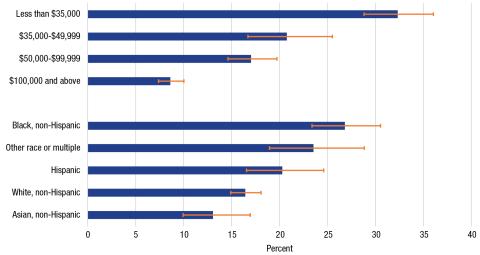

Low-income households are especially likely to report that their children were unable to attend care, true of one in three households with incomes below $35,000 (see Figure 1). However, even among households with incomes over $100,000, 20 percent reported this constraint. This disparity suggests that while low-income households fare the worst, even a higher income is insufficient protection from childcare challenges.

Figure 1. Percent of Households with Children Under Age 12 Reporting Any Children Unable to Attend Child Care in Past Four Weeks, July–October 2021

Note: Estimates are weighted using household-level replicate weights. Bars represent 95% (logit) confidence intervals. “Hispanic” includes respondents identifying as Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish. Source: U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey, Weeks 34–39.

Looking across racial-ethnic groups, non-Hispanic Black respondents were most likely to report inadequate access to childcare (32 percent), followed by respondents reporting “other” or multiple races (31 percent), and Hispanic respondents (27 percent). In part, this is traceable to disparities that existed prior to the pandemic, with Hispanic and American Indian/Alaska Native communities disproportionately represented among Census tracts with a low childcare supply.5

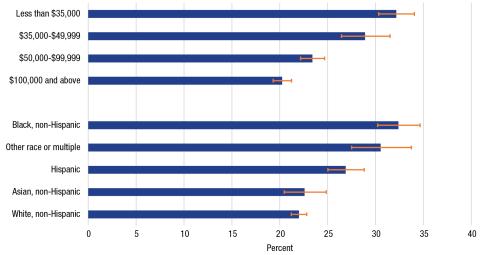

Figure 2. Percent Reporting an Adult in The Household Left or Lost a Job As a Result of Child Under Age 12 Being Unable to Attend Child Care in Past Four Weeks, July–October 2021

Note: Estimates are weighted using household-level replicate weights. Bars represent 95% (logit) confidence intervals. “Hispanic” includes respondents identifying as Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish. Source: U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey, Weeks 34–39.

Parents’ capacity for employment is deeply linked to childcare availability, and this remains true in 2021. Among the 5 million households reporting inadequate access to childcare in the past four weeks, one in five reported that an adult in the household had left or lost a job because of the time needed to provide care for their children. The prevalence of this response maps closely to race/ethnicity and household finances, as shown in Figure 2: Black and Hispanic parents and adults in low-income households were more likely to leave their job or lose their job because of inadequate access to childcare.

Among those facing inadequate childcare access, roughly one-third of households with incomes less than $35,000 had left or lost a job because of time away needed to care for children—almost four times the prevalence among households with incomes at $100,000 or more (8.7 percent). Compared to other racial-ethnic groups, non-Hispanic Black respondents were not only more likely to experience childcare constraints, they were also more likely to leave or lose their job as a result. Over one-quarter of Black respondents who lacked childcare reported that an adult in the household left or lost their job in the past four weeks as a result of the time needed to provide care for their children, as did one in five Hispanic respondents. In comparison, just 16.5 percent of non-Hispanic White respondents and 13 percent of non-Hispanic Asian respondents with inadequate access to childcare left or lost a job as a result.

These gaps are driven in part by differential exposure to frontline essential occupations that require in-person work, and disparities in the existence and quality of employment benefits, such as access to flexible schedules, remote work opportunities, and paid leave.6 Households with these benefits can more nimbly respond to childcare challenges by strategically combining leave and flexibility, whereas households without these benefits may be forced to choose between work and care. In the short term, these employment disruptions reduce household resources available for meeting immediate needs. In the longer-term, periods of unemployment are linked to worse lifetime career outcomes, further entrenching inequalities between different types of workers.7

Conclusion

Foremost, this research brief demonstrates that any illusion that the childcare crises of early 2020 were transitory and now resolved is incorrect. A year and a half into the pandemic, close to one-quarter of households with children under 12 report inadequate access to childcare over the past month. Moreover, for one-fifth of those households, this lack of access triggered a household employment loss, further destabilizing income for vulnerable families and contributing to workforce shortages experienced by employers.

Just as important, however, our study illustrates multiple and overlapping forms of disadvantage. Not only are people of color and those with lower income more likely to face inadequate access to childcare, they are also more likely to lose work because of these challenges. These job losses amplify economic precarity. Black, Hispanic, and low-income families have faced disproportionate hardship on nearly every dimension of the pandemic, challenges that only exacerbate existing inequalities. Research has already documented a lack of childcare slots in neighborhoods of color alongside a disproportionate pandemic-era loss of childcare centers in census tracts where families of color live.8 Our research brief suggests that those families are experiencing the economic reality of those shortages in near-real time.

In the immediate term, efforts to stem childcare losses due to temporary or permanent closure should be a top priority. Short-term closures are inherently connected to workforce shortages, and even where licensed capacity exists, not all slots are available. Nationwide, the childcare workforce still has 108,000 fewer workers than it did in February 2020.9 This loss is unprecedented but unsurprising for a sector that demands educated workers but pays a wage averaging one-third of what similarly credentialed peers in public schools earn.10 Efforts to immediately increase wages for the sector are critical for stabilizing supply. In the short term, funding from the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) provides considerable opportunity for supporting individual early educators in this way.11

The flexibilities of ARPA that, for example, establish and incentivize pathways to licensure, build provider capacity through start-up grants and technical assistance, and realign methods for calculating reimbursements to providers who accept childcare subsidies, represent promising steps forward. Each of these efforts could be targeted toward building childcare supply and stability in neighborhoods where families of color or families with low incomes are clustered, and, in some states, this is an emerging priority. Future research that evaluates these flexibilities will provide an important evidence base to inform long-term solutions.

Despite the possibility the ARPA brings, it is still a one-time injection of federal funds, necessary for stabilization, but not sufficient to solve the sector’s enduring problems. A more permanent solution would treat childcare as a public good. The most prominent pathway toward such long-term investment is via the Build Back Better Act, which is currently under consideration. The proposed legislation includes a framework for substantially expanding access to pre-kindergarten in school and childcare settings. It also includes an expanded childcare subsidy program that would ensure families below 250 percent of state median income do not pay more than 7 percent of their income on care and the lowest income families pay nothing. A recent analysis found that such a cap would reduce poverty among Black and Hispanic New Englanders.12

Importantly, the proposed changes to the childcare subsidy program would require states to calculate reimbursements to providers in a way that better aligns with the true cost of care, including appropriate wages for early educators. Steady injections of federal funding for pre-kindergarten and wider receipt of childcare subsidies that better match the cost of care delivery would buffer childcare providers in various settings from the thin and inconsistent operating margins that have plagued the sector and disincentivized providers from accepting families relying on subsidies. As a result, providers might be better able to respond to childcare demand in a traditional market sense, expanding into areas to offer affordable access to families who have been historically most underserved.

Data are from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, Weeks 34–39 (July 21, 2021–October 11, 2021). The sample is restricted to U.S. residents aged 18 and older living in households with at least one child under the age of 12. Inadequate access to childcare was measured with the following survey question: “At any time in the last 4 weeks, were any children in the household unable to attend daycare or another childcare arrangement as a result of childcare being closed, unavailable, unaffordable, or because you are concerned about your child’s safety in care?” Our analysis includes respondents who answered ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ to this question and excludes respondents with missing values (25%). These high rates of missing values may lead to underestimates of the true prevalence of inadequate access to childcare in the population. Survey respondents who reported inadequate access to childcare were then asked, “which of the following occurred in the last 4 weeks as a result of childcare being closed or unavailable? The answer choices included “you (or a member of your household) left a job to care for children” and “you (or a member of your household) lost a job because of time away to care for your children.” Respondents were allowed to select either or both. Race-ethnicity was measured by combining answers to two survey questions, one asking if they were of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin and another asking if they were White, alone; Black, alone; Asian, alone; any other race alone or in combination. Household income in the HPS is coded in relatively wide bins (less than $25,000; $25,000–$34,999; $35,000–$49,999; $50,000–$74,999; $75,000–$99,999; $100,000–$149,999; $150,000–$199,999; $200,000 and above). To preserve space, we collapsed categories to less than $35,000; $35,000 to $49,000; $50,000 - $99,000; $100,000 or more. In regression analyses we use listwise deletion to exclude those with missing values for household income (~25%). Household weights are applied to account for non-response bias and representativeness.

- U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Remarks by Secretary of the Treasury Janey L. Yellen on Shortages in the Child Care System”, 2021. Accessed from: https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0355.

- J.A. Carson and M.J. Mattingly, “COVID-19 Didn’t Create a Child Care Crisis, But Hastened and Inflamed It,” Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire, 2020; D.L. Carlson, R.J. Petts, and J.R. Pepin, “Changes in US Parents’ Domestic Labor During the Early Days of the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Sociological Inquiry, 2021; C. Collins, L.C. Landivar, L. Ruppanner, and W.J. Scarborough, “COVID?19 and the gender gap in work hours,” Gender, Work & Organization, 28 (2021): 101–112; N. Bateman and M. Ross, “Why has COVID-19 been especially harmful for working women?” The Brookings Institute, 2020; J.M. Calarco, E. Anderson, E. Meanwell, and A. Knopf, “‘Let’s Not Pretend It’s Fun’: How COVID-19-Related School and Childcare Closures Are Damaging Mothers’ Well-Being,” SocArXiv, 2020; C. Novoa, “How Child Care Disruptions Hurt Parents of Color Most,” The Center for American Progress, 2020. Accessed from: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/child-care-disruptions-hurt-parents-color/; W. Raderman, “Pandemic Childcare Issues Give Good Reason to Invest in Families,” Data For Progress, 2021. Accessed from: https://www.dataforprogress.org/blog/2021/11/11/pandemic-childcare-issues-give-good-reason-to-invest-in-families.

- Recent research has documented profound gender disparities in parents’ experiences of and responses to inadequate access to childcare during COVID-19. We focus here on social class and race disparities and leave gender disparities (and their intersections with race and class) for future work.

- U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, September 29, 2021–October 12, 2021 (week 39). Estimate is weighted at the household level for non-response bias and representativeness. This estimate is drawn from Week 39, although weighted household estimates of inadequate access to childcare in Weeks 34 through 38 separately show that this count is remarkably similar across the July through October 2021 period and does not vary meaningfully between summer and fall.

- M. Rasheed and K. Hamm, “Mapping America’s Child Care Deserts,” The Center for American Progress, 2017.

- I. Sawhill, S. Nzau, and K. Guyot, “A primer on access to and use of paid family leave,” The Brookings Institute, 2019; M. Lavietes, “Working from home during pandemic found widening U.S. inequality,” Reuters, 2021.

- D.H. Cooper, “The Effect of Unemployment Duration on Future Earnings and Other Outcomes,” Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 2013; M. Gangl, “Scare Effects of Unemployment: An Assessment of Institutional Complementarities,” American Sociological Review, 2006.

- E. Lee and Z. Parolin, “The Care Burden during COVID-19: A National Database of Child Care Closures in the United States,” 2021.

- BLS Current Employment Statistics Survey, seasonally adjusted, November 1, 2021.

- C. McLean, L.J.E. Austin, M. Whitebook, and K.L. Olson “Early Childhood Workforce Index - 2020,” Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkely, 2021.

- States received their allocations from the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, and in turn are expected to provide subgrants to eligible child care providers. These funds have considerable flexibility, including to invest in facilities improvement, workforce bonuses, training opportunities, or recouping losses from closures. While most states are in the process of disseminating these funds, at the time of this writing, there are still seven states that have not made a subgrant application available to their childcare providers. See https://childcareta.acf.hhs.gov/state-and-territory-childcare-stabilization-grant-applications.

- M.J. Mattingly and J. Carson, “Proposal to Offset Families’ Child-Care Costs Could Enhance Equity by Dramatically Cutting Poverty Among People of Color Across New England,” Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 2021.

- Jonathan Koltai is an assistant professor of sociology at the University of New Hampshire.

- Jess Carson is a research assistant professor at the University of New Hampshire’s Carsey School of Public Policy.

- Tyrus Parker is a doctoral student in sociology at the University of New Hampshire.

- Rebecca Glauber is an associate professor of sociology at the University of New Hampshire and a faculty fellow at the Carsey School of Public Policy.

Among those facing inadequate childcare access, roughly one-third of households with incomes less than $35,000 had left or lost a job because of time away needed to care for children—almost four times the prevalence among households with incomes at $100,000 or more (8.7 percent). Compared to other racial-ethnic groups, non-Hispanic Black respondents were not only more likely to experience childcare constraints, they were also more likely to leave or lose their job as a result. Over one-quarter of Black respondents who lacked childcare reported that an adult in the household left or lost their job in the past four weeks as a result of the time needed to provide care for their children, as did one in five Hispanic respondents. In comparison, just 16.5 percent of non-Hispanic White respondents and 13 percent of non-Hispanic Asian respondents with inadequate access to childcare left or lost a job as a result.

These gaps are driven in part by differential exposure to frontline essential occupations that require in-person work, and disparities in the existence and quality of employment benefits, such as access to flexible schedules, remote work opportunities, and paid leave.6 Households with these benefits can more nimbly respond to childcare challenges by strategically combining leave and flexibility, whereas households without these benefits may be forced to choose between work and care. In the short term, these employment disruptions reduce household resources available for meeting immediate needs. In the longer-term, periods of unemployment are linked to worse lifetime career outcomes, further entrenching inequalities between different types of workers.7

Foremost, this research brief demonstrates that any illusion that the childcare crises of early 2020 were transitory and now resolved is incorrect. A year and a half into the pandemic, close to one-quarter of households with children under 12 report inadequate access to childcare over the past month. Moreover, for one-fifth of those households, this lack of access triggered a household employment loss, further destabilizing income for vulnerable families and contributing to workforce shortages experienced by employers.

Just as important, however, our study illustrates multiple and overlapping forms of disadvantage. Not only are people of color and those with lower income more likely to face inadequate access to childcare, they are also more likely to lose work because of these challenges. These job losses amplify economic precarity. Black, Hispanic, and low-income families have faced disproportionate hardship on nearly every dimension of the pandemic, challenges that only exacerbate existing inequalities. Research has already documented a lack of childcare slots in neighborhoods of color alongside a disproportionate pandemic-era loss of childcare centers in census tracts where families of color live.8 Our research brief suggests that those families are experiencing the economic reality of those shortages in near-real time.

In the immediate term, efforts to stem childcare losses due to temporary or permanent closure should be a top priority. Short-term closures are inherently connected to workforce shortages, and even where licensed capacity exists, not all slots are available. Nationwide, the childcare workforce still has 108,000 fewer workers than it did in February 2020.9 This loss is unprecedented but unsurprising for a sector that demands educated workers but pays a wage averaging one-third of what similarly credentialed peers in public schools earn.10 Efforts to immediately increase wages for the sector are critical for stabilizing supply. In the short term, funding from the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) provides considerable opportunity for supporting individual early educators in this way.11

The flexibilities of ARPA that, for example, establish and incentivize pathways to licensure, build provider capacity through start-up grants and technical assistance, and realign methods for calculating reimbursements to providers who accept childcare subsidies, represent promising steps forward. Each of these efforts could be targeted toward building childcare supply and stability in neighborhoods where families of color or families with low incomes are clustered, and, in some states, this is an emerging priority. Future research that evaluates these flexibilities will provide an important evidence base to inform long-term solutions.

Despite the possibility the ARPA brings, it is still a one-time injection of federal funds, necessary for stabilization, but not sufficient to solve the sector’s enduring problems. A more permanent solution would treat childcare as a public good. The most prominent pathway toward such long-term investment is via the Build Back Better Act, which is currently under consideration. The proposed legislation includes a framework for substantially expanding access to pre-kindergarten in school and childcare settings. It also includes an expanded childcare subsidy program that would ensure families below 250 percent of state median income do not pay more than 7 percent of their income on care and the lowest income families pay nothing. A recent analysis found that such a cap would reduce poverty among Black and Hispanic New Englanders.12

Importantly, the proposed changes to the childcare subsidy program would require states to calculate reimbursements to providers in a way that better aligns with the true cost of care, including appropriate wages for early educators. Steady injections of federal funding for pre-kindergarten and wider receipt of childcare subsidies that better match the cost of care delivery would buffer childcare providers in various settings from the thin and inconsistent operating margins that have plagued the sector and disincentivized providers from accepting families relying on subsidies. As a result, providers might be better able to respond to childcare demand in a traditional market sense, expanding into areas to offer affordable access to families who have been historically most underserved.

Data are from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, Weeks 34–39 (July 21, 2021–October 11, 2021). The sample is restricted to U.S. residents aged 18 and older living in households with at least one child under the age of 12. Inadequate access to childcare was measured with the following survey question: “At any time in the last 4 weeks, were any children in the household unable to attend daycare or another childcare arrangement as a result of childcare being closed, unavailable, unaffordable, or because you are concerned about your child’s safety in care?” Our analysis includes respondents who answered ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ to this question and excludes respondents with missing values (25%). These high rates of missing values may lead to underestimates of the true prevalence of inadequate access to childcare in the population. Survey respondents who reported inadequate access to childcare were then asked, “which of the following occurred in the last 4 weeks as a result of childcare being closed or unavailable? The answer choices included “you (or a member of your household) left a job to care for children” and “you (or a member of your household) lost a job because of time away to care for your children.” Respondents were allowed to select either or both. Race-ethnicity was measured by combining answers to two survey questions, one asking if they were of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin and another asking if they were White, alone; Black, alone; Asian, alone; any other race alone or in combination. Household income in the HPS is coded in relatively wide bins (less than $25,000; $25,000–$34,999; $35,000–$49,999; $50,000–$74,999; $75,000–$99,999; $100,000–$149,999; $150,000–$199,999; $200,000 and above). To preserve space, we collapsed categories to less than $35,000; $35,000 to $49,000; $50,000 - $99,000; $100,000 or more. In regression analyses we use listwise deletion to exclude those with missing values for household income (~25%). Household weights are applied to account for non-response bias and representativeness.

- U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Remarks by Secretary of the Treasury Janey L. Yellen on Shortages in the Child Care System”, 2021. Accessed from: https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0355.

- J.A. Carson and M.J. Mattingly, “COVID-19 Didn’t Create a Child Care Crisis, But Hastened and Inflamed It,” Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire, 2020; D.L. Carlson, R.J. Petts, and J.R. Pepin, “Changes in US Parents’ Domestic Labor During the Early Days of the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Sociological Inquiry, 2021; C. Collins, L.C. Landivar, L. Ruppanner, and W.J. Scarborough, “COVID?19 and the gender gap in work hours,” Gender, Work & Organization, 28 (2021): 101–112; N. Bateman and M. Ross, “Why has COVID-19 been especially harmful for working women?” The Brookings Institute, 2020; J.M. Calarco, E. Anderson, E. Meanwell, and A. Knopf, “‘Let’s Not Pretend It’s Fun’: How COVID-19-Related School and Childcare Closures Are Damaging Mothers’ Well-Being,” SocArXiv, 2020; C. Novoa, “How Child Care Disruptions Hurt Parents of Color Most,” The Center for American Progress, 2020. Accessed from: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/child-care-disruptions-hurt-parents-color/; W. Raderman, “Pandemic Childcare Issues Give Good Reason to Invest in Families,” Data For Progress, 2021. Accessed from: https://www.dataforprogress.org/blog/2021/11/11/pandemic-childcare-issues-give-good-reason-to-invest-in-families.

- Recent research has documented profound gender disparities in parents’ experiences of and responses to inadequate access to childcare during COVID-19. We focus here on social class and race disparities and leave gender disparities (and their intersections with race and class) for future work.

- U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, September 29, 2021–October 12, 2021 (week 39). Estimate is weighted at the household level for non-response bias and representativeness. This estimate is drawn from Week 39, although weighted household estimates of inadequate access to childcare in Weeks 34 through 38 separately show that this count is remarkably similar across the July through October 2021 period and does not vary meaningfully between summer and fall.

- M. Rasheed and K. Hamm, “Mapping America’s Child Care Deserts,” The Center for American Progress, 2017.

- I. Sawhill, S. Nzau, and K. Guyot, “A primer on access to and use of paid family leave,” The Brookings Institute, 2019; M. Lavietes, “Working from home during pandemic found widening U.S. inequality,” Reuters, 2021.

- D.H. Cooper, “The Effect of Unemployment Duration on Future Earnings and Other Outcomes,” Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 2013; M. Gangl, “Scare Effects of Unemployment: An Assessment of Institutional Complementarities,” American Sociological Review, 2006.

- E. Lee and Z. Parolin, “The Care Burden during COVID-19: A National Database of Child Care Closures in the United States,” 2021.

- BLS Current Employment Statistics Survey, seasonally adjusted, November 1, 2021.

- C. McLean, L.J.E. Austin, M. Whitebook, and K.L. Olson “Early Childhood Workforce Index - 2020,” Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkely, 2021.

- States received their allocations from the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, and in turn are expected to provide subgrants to eligible child care providers. These funds have considerable flexibility, including to invest in facilities improvement, workforce bonuses, training opportunities, or recouping losses from closures. While most states are in the process of disseminating these funds, at the time of this writing, there are still seven states that have not made a subgrant application available to their childcare providers. See https://childcareta.acf.hhs.gov/state-and-territory-childcare-stabilization-grant-applications.

- M.J. Mattingly and J. Carson, “Proposal to Offset Families’ Child-Care Costs Could Enhance Equity by Dramatically Cutting Poverty Among People of Color Across New England,” Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 2021.

- Jonathan Koltai is an assistant professor of sociology at the University of New Hampshire.

- Jess Carson is a research assistant professor at the University of New Hampshire’s Carsey School of Public Policy.

- Tyrus Parker is a doctoral student in sociology at the University of New Hampshire.

- Rebecca Glauber is an associate professor of sociology at the University of New Hampshire and a faculty fellow at the Carsey School of Public Policy.