download the brief

Key Findings

UPDATE: This fact sheet was updated on October 24, 2024, to reflect analytics corrections to some estimates.

How often are low-income families pushed into poverty by their child care expenses? In this fact sheet, we use the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) to assess the extent to which child care expenses are pushing families with young children into poverty.

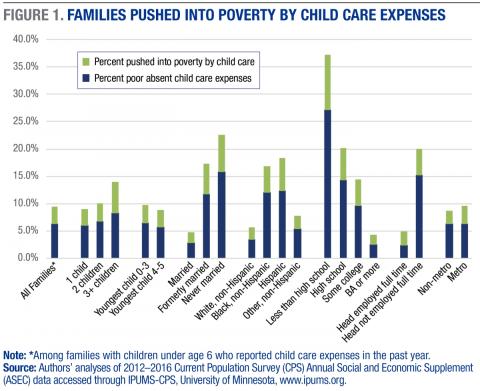

Nearly one-third (30.4 percent) of families with young children are poor. To fall under the SPM poverty line means that a family’s income would be less than $26,000 a year on average, with variations by family composition and geographic location. Among poor families with young children, 12.6 percent incur child care expenses according to our analyses of the SPM. For families earning this little income, child care expense can be a burden. Of those who pay for child care, nearly one in ten (9.6 percent) are poor (Figure 1). Roughly one third of these poor families are pushed into poverty by child care expenses. This represents an estimated 177,000 families.1

Among families with young children who pay for child care, those with three or more children, those headed by a single parent, those with black or Hispanic household heads, and those headed by someone with less than a high school degree or by someone who does not work full time are most often pushed into poverty by child care expenses. Notably, these are also the families that tend to have the highest rates of poverty.

Child care is complex for many families, and this analysis touches only on the expenses that families are paying out of pocket, whether the arrangement is adequate or not. Many of these families might prefer to spend more, if they could afford it, to gain higher-quality care or more hours of care. This analysis also does not touch on families who obtain child care through non-cash means, such as reliance on relatives; trading of child care; split-shift parenting, where work schedules are staggered so that child care is less necessary; or publicly supported programs such as Head Start and public preschool. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that lowering out-of-pocket child care expenses for families with young children would serve to reduce poverty. Additionally, things like increased subsidies may expand access to higher quality child care or open the door to increased labor force participation.

Data and Methods

To analyze the effects of child care expenses on the poverty rate, we assembled a data file consisting of the five most recent years, 2012–2016 (capturing poverty from 2011–2015) of the Current Population Survey’s Annual Social and Economic Supplement, downloaded from IPUMS.2 Because child care expenses are combined with other work-related expenses in the SPM, we first create a somewhat different version of the SPM to look specifically at child care expenses. We add back in combined work and child care expenses and then subtract from resources total uncapped out-of-pocket child care expenses. The measure thus deviates from the SPM by the fact that other work-related expenses are not subtracted from resources, and subtracted child care expenses are not capped at the level of the lowest-earning spouse or partner. Once these changes are made, we simply recalculate poverty rates and related statistics using this alternative definition of resources, with and without the subtraction of out-of-pocket child care expenses.

Endnotes

1. Note that for the purposes of this brief, we depart from U.S. Census Bureau methodology and use uncapped child care expenses to capture cases even where these expenses exceed secondary earner income. Throughout this brief, we use the term “family” to refer to a Supplemental Poverty Measure unit, as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. All analyses are restricted to families with at least one child under age 6 who report any child care expenses.

2. Sarah Flood, Miriam King, Steven Ruggles, and J. Robert Warren, Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Current Population Survey: Version 4.0 [dataset] (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2015), http://doi.org/10.18128/D030.V4.0.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jessica Carson, Michele Dillon, Michael Ettlinger, Andrew Schaefer, and Kristin Smith of the Carsey School of Public Policy for comments on an earlier draft; Patrick Watson for his editorial assistance; and Laurel Lloyd and Bianca Nicolosi at the Carsey School for their layout assistance.

This research was made possible by a gift from Jay Robert Pritzker and Mary Kathryn Pritzker.