Key Findings

Introduction

College costs and persistent workforce shortages have prompted educators, policymakers, and employers to shift the conversation on the transition from school from a narrow “college for all” emphasis to a broader “postsecondary education” and “career pathways” perspective.1 The timing of this shift coincides with current and anticipated workforce needs; by 2032, New Hampshire will have 197,000 positions available across its top 80 occupations, with labor force growth projected to fill only 6,100 of those jobs.2 Even for college-bound individuals, greater scrutiny is being applied to the value of different degree choices relative to lifetime earnings,3 with powerful online tools and calculators now available to help weigh options.4 Industry has also gotten involved by designing apprenticeship and training programs that meet their own workforce needs while also moving trainees into valuable credentialing pathways.5

With public debates about the value of college escalating6 and demographic forecasts threatening to reshape higher education,7 K–12 institutions are adapting by engaging youth more deliberately in “learning for careers” as they approach graduation.8 Some commentators argue that broadening options to include career and technical education (CTE), certificates, and 2-year degrees—while recognizing the earnings still afforded by a college degree—is essential for realizing equity gains across racial and socioeconomic groups.9 Successfully building such pathways cannot be accomplished by educational institutions alone; it requires collaboration across public, nonprofit, and private sectors, as well as financial and policy incentives that reduce barriers and risks.

This paper describes an innovative effort to address these challenges in New Hampshire, focusing on a set of programs that follow a “hyperlocal” approach to career pathway development. Seeking to expose participants to careers in high-demand areas, the programs simultaneously address specific, local industry, community, and individual needs. Their purpose is to increase the likelihood of social mobility by using career exposure and hands-on involvement to spur interest and motivation toward additional education and training in promising fields. The research reported here focused on programs that target youth approaching the secondary-postsecondary transition.

The paper begins by briefly describing New Hampshire’s unique demographic characteristics as they relate to the state’s approach to education and workforce development. The characteristics help us understand the challenges involved in helping individuals make the transition from secondary education to postsecondary roles. The study’s main findings focus on key elements of career pathway programs that align with the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation’s (NHCF) hyperlocal model. Excerpts from participant interviews across six programs help to show what works in different career pathway sites, in terms of realizing effective collaboration among partners and providing learners with a positive experience. The paper concludes with a discussion about areas of ongoing need both within and outside of individual pathway programs.

Background and Context: Demographic Conditions in New Hampshire

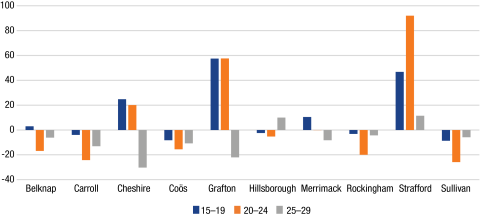

New Hampshire is one of the three oldest states in the United States by median age.10 The state’s older population is connected to the realities of outmigration among older adolescents and young adults (see Figure 1), including a majority of college-bound New Hampshire youth pursuing their education elsewhere (59 percent—the highest average percentage in the United States11). According to recent reports issued by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas and the University of New Hampshire, New Hampshire is also one of the least “sticky” states in the United States in terms of the number of native-born residents who stay into adulthood and the number of people who stay after relocating to New Hampshire.12 The Dallas Fed report attributes stickiness to job availability, housing affordability, favorable temperatures, and proximity to urban centers; these are all reasons young people may choose to stay or leave their home states. A lack of stickiness can stymie economic growth by contributing to an unstable workforce, a condition that is not typically relieved by an in-migration of older adults.13 New Hampshire counties with institutions of higher education (Cheshire, Grafton, and Strafford) have higher populations of young adults, and as Figure 1 shows, retention in New Hampshire counties without institutions of higher education has been challenging.

Outmigration of youth and young adults is not a new issue in New Hampshire. In fact, it prompted a report in 2009 by the Governor’s Task Force for the Recruitment and Retention of a Young Workforce for the State of New Hampshire which reported:

- Sixty-six percent of UNH freshmen surveyed expressed a desire to leave the state and experience something “different.”

- College students’ perception of job availability is linked to their desire to stay or leave New Hampshire.

- Of the students surveyed, only 17 percent of out-of-state students planned on staying in New Hampshire, versus 57 percent of in-state students.

Project Background

The NH Business and Industry Association (BIA) and NH Charitable Foundation (NHCF) co-funded an effort to bridge workforce needs and access to good jobs for those facing barriers. Through this effort, the Workforce Accelerator 2025 workgroup formed to activate businesses so they can work in concert with local partners to foster access for individuals who had been marginalized from existing pathways. This early work coalesced into the Career Pathways Partnership grant program in January of 2020. For the first 18 months, grants were co-funded by BIA and NHCF. NHCF assumed responsibility for the program in June 2021.

Each program site ideally involves four entities:

- A participant group (youth or adults who could benefit)

- A business-supporting agency (e.g., Chamber of Commerce)

- A credentialing organization

- Businesses/workplaces in high-demand areas

Examples of the kinds of programs a Career Pathways Partnership grant supports can be found on the NHCF website.14 One featured program focused on exposing students to criminal justice careers and involved Salem High School, the Salem Police Department, and Nashua Community College. Students in that program visit the police department during an extended learning opportunity (defined below) to learn core skills and speak to department personnel about law enforcement careers, which are further explored during a community college course providing a broader view of the field.

Participants in the study discussed in this paper came from career and technical education (CTE) programs, Chambers of Commerce, community colleges, and various businesses/workplaces reflecting a range of sites and career focuses.

Figure 1. Net Migration per 100 Residents Among 15–19, 20–24, and 25–29 Age Cohorts 2010–2019, by County15

Source: Data retrieved from: https://netmigration.wisc.edu/

These findings suggest that retaining youth is a good investment but won’t happen automatically. The Governor’s Task Force report has since yielded a number of positive outgrowths related to this objective. First, it launched Stay Work Play NH,16 a nonprofit organization tasked with promoting New Hampshire as a place to live, learn, and work. Second, it prompted attention on the importance of industry involvement in career pathway development. It also recognized the challenges to small- and mid-sized businesses in hosting high school-age apprentices, which sparked the development of business tax credit programs to incentivize industry involvement.17 Third, it recognized the importance of messaging about career opportunities through peers and social networks, an example of which can be seen in the recent IBuild NH campaign, jointly produced by NH PBS and the Associated Builders and Contractors NH/VT Chapter.18

Research Methods and Data

This study examined collaborations among schools, industry partners, business-supporting agencies, and credentialing organizations at six career pathway programs around New Hampshire that receive small grants (<$10,000) from the NHCF’s Career Pathways grant program. Twenty-one semi-structured interviews were conducted between fall 2022 and summer 2023 with representatives from schools (7 CTE program directors or teachers, 5 students), community college partners (3 individuals), Chambers of Commerce (4 directors and program staff), and businesses (4 owners/managers/representatives). Interviews were transcribed and thematically coded. Interview excerpts were selected to represent core ideas in the main themes. Due to the study’s participation agreements, names of sites, organizations, and individuals are withheld to maintain confidentiality. The study was approved by the UNH Institutional Review Board (IRB-FY2023-33).

Key Definitions

Career pathways: This phrase refers to “the coordination of people and resources” by secondary and postsecondary educational institutions and industry organizations that “assist youth and adults with acquiring marketable skills and industry-recognized credentials through better alignment of education, training and employment, and human and social services among public agencies and with employers.”19 NHCF funding targets participants in need who can benefit most from career preparation and jobs that provide a sustaining wage.

Career and Technical Education (CTE): According to the national non-profit association Advance CTE, career, and technical education “provides students of all ages with the academic and technical skills, knowledge, and training necessary to succeed in future careers and to become lifelong learners. In total, about 12 million high school and college students are enrolled in CTE across the nation. CTE prepares these learners for the world of work by introducing them to workplace competencies and makes academic content accessible to students by providing it in a hands-on context.”20 There are 31 CTE centers in New Hampshire.21

Business-supporting agency: Business-supporting agencies may include Chambers of Commerce, regional Economic Development Corporations (EDCs),22 or other facilitating economic development agencies who act as brokers between partners and assist with program expansion.

Credentialing organization: Career pathways involve industry recognized credentials (IRCs) participants can earn including licenses, certificates, certifications, badges, or other accepted skill verifications. These may be provided by associations, private companies, or other organizations. Credentials may also be college-level credits often earned alongside high school graduation requirements, sometimes accumulating to an associate degree and often transferable into a 4-year college or university.

Industry partner: Industry partners are workplaces that agree to provide work-integrated learning experiences ranging from single site visits to long-term apprenticeships. Industry partners differ from employers by their shared commitment to learning in addition to teaching specific workplace skills. As one industry partner interviewed for this study put it, “we’re not building good chefs, we’re building good humans. … it’s your job to foster that environment for them.”

Extended learning opportunities (ELOs): According to the NH Department of Education, ELOs “validate the learning that takes place outside of school that is youth centered and focuses both on the acquisition of skills and knowledge and on youth development.” Many NH schools have ELO coordinators and award credit for ELO experiences with community-based, industry, or academic partners. ELOs are further supported by the NH ELO Network.23

Despite progress in these important areas, a 2020-2021 study by UNH’s Youth Retention Initiative researchers24 found that the messages circulating around New Hampshire about youths’ futures still resemble observations made by the 2009 Governor’s Task Force: there is still widespread sentiment that youth “need to ‘leave to succeed’” and “that young workers should leave the state and only come back in mid?life after they have ‘made something of themselves.’” Such messages normalize leaving NH as a necessary part of development and implicitly devalue and stigmatize opportunities to stay.

Youth messaging remains a clear challenge in the Granite State. Concrete action and partnerships to build viable career pathways are needed so that new messaging about the benefits of staying and/or moving to New Hampshire are better aligned with opportunities. Organizing these pathways takes coordination among agencies serving individual participants, industry partners, postsecondary or credentialing institutions, and organizations that support local businesses. NHCF’s Career Pathway sites reflect collaborations among these partners. What are some of the nuances critical for making these partnerships work?

Research Findings

In our interviews with NHCF Career Pathway site participants, we identified several themes associated with successful initiatives. At the institutional level, participants identified the importance of collaborative partnerships and creativity and flexibility. On the student experience side, the importance of exposure and hands-on engagement emerged. People working at the sites also spoke about some of the barriers and needs facing career pathway programs.

Collaborative Partnerships

The NHCF program centers collaboration as a key dimension for successful career pathway programs. For instance, in order for students to access extended learning opportunities that link their CTE program and/or classes at a community college, partnerships need to form and be maintained over time. As Michael Turmelle, NHCF Director of Education and Career Initiatives,25 explained,

If we can teach people how to make these partnerships, then they can replicate it. … And when you come to the table with that spirit of cooperation and coordination you can actually solve problems, and workforce problems are not insurmountable.

School CTE programs, industry, and business-supporting agencies like Chambers of Commerce all play important roles in the career pathway process. Chambers of Commerce play an especially useful role in the process of networking and relationship building among industry members and school CTE programs.

One of the Chamber directors participating in this study concurred with Michael Turmelle: “All we need is a collaborative group of people that are willing to do something.” Another Chamber director shared that the partners involved at their site approached the initiative with shared goals and the spirit of collaboration: “The easy part is that everybody’s on board. They want to see something happen. So, there’s that conversation of, ‘Okay, we know we want growth and there are opportunities here, so let’s figure out how we can work together.’”

Figuring out how to work together involves several related, critical ingredients, most prominently taking time to learn and building trust. As one CTE director said about the process of building partnerships, “figure out who your touchstones are in the community as far as fellow collaborators.” She explained that this early networking process is not only important for meeting potential collaborators, but also for determining the “fit,” as she put it, between different partners, program objectives, and operational needs. A different CTE director described how she took time to visit with people to explore and build partnerships:

When I became the director, I spent probably the first month and a half spending time with teachers and finding out what they needed, what they were missing, what students were feeling. Then I probably spent the next couple of months networking in that town. I did not live [there] so I had to visit industry [workplaces]. I spent a lot of time at the local town offices and things like that trying to determine what areas they were lacking … and how we could help them maybe fill some voids in healthcare or whatever it was.

Taking the time to learn and develop partnerships that include mutual trust-building are essential for meeting the needs of each career pathway initiative and greater community and/or industry needs. One industry representative explained the mindset he brings to the effort: “I have been on many boards and tried to keep my focus on the betterment of our community first and foremost.” A manager of a medium-sized business in northern NH seeking to engage high school apprentices echoed this point and noted the importance of community involvement by industry partners:

We tried to get [into the high school] for job fairs, and they were like, “we can’t just let [your company] walk into our school and have a job fair.” … I think number one is trying to get introductions to those contacts in the community, like the superintendent, the principal of the school. But also, one thing we’ve done—I’ve kind of learned this from some of my predecessors—[is] getting involved with the community, with nonprofits. So, you’re part of the community. And then you become a little more open to families that trust your business.

Career pathway initiatives can benefit from the continued spirit of collaboration and trust building throughout the process. When partners encounter barriers, school and industry partners, along with Chambers of Commerce, can develop solutions together. One of the Chamber representatives talked about their relationship with a CTE program in the context of other youth programs they offer:

Anytime we’re working with students in any other capacity, there’s so much we have to do in terms of consent forms and permissions. And [the school just takes] care of all of those pieces. … There’s a lot of red tape but we never see it through that particular program.

Another industry partner explained how trust helps to ease program logistics and leads to reciprocated growth throughout the program itself:

Everything’s been pretty smooth. They’ve given us some good freedom to do things we’d like to do with the kids and give them the most hands on experience. … I don’t think there’s much to be done that can improve it. … I mean, the class speaks for itself, going from eight to 21 [students].

Modest expectations at the outset can also be helpful, as the overall process of building a career pathway initiative can feel daunting and time consuming. The advice one Chamber director provided was “to just keep it really simple. Don’t overcomplicate it: crawl, walk, run. Find one way to partner your industry folks with the school and connect the students.”

Creativity and Flexibility

Youth workforce development programming and opportunities in schools and workplaces have different kinds of logistical needs involving regulatory compliance, schedules, transportation, supervision, and so on. Because of these factors, participants (i.e., students and partners) can encounter barriers that inhibit participation and derail progress. Well-intentioned plans may require creative and flexible revision over time to make programs more effective at meeting student needs.

The considerations of scheduling and staffing flexibility may determine an organization’s feasibility as a partner. A story shared by a Chamber director in southern NH captures both how logistically complicated a program can be, and the kind of creativity required to surmount the problems they identified in early phases of the partnership:

When we started [the first program], recognizing that very few kids had their own vehicles, whatever program that’s off campus has to take place during school hours. It can’t take place after school. So that meant that we had to pull students out … and then somehow figure out “how do we get them from [school] and back before the bell rings to go home?” So, we partnered with [their local] Chamber of Commerce because they knew their community better than we did. And they put me in touch with the Boys and Girls Club that has vehicles. So, I contracted out with them to be our transportation provider for [that site].

Another site faced different scheduling issues. The instructor of the community college course affiliated with the program explained how unplanned events like snow days and exams created conflicts that required shifting their course schedule, which she was able to accommodate. The CTE director of that particular site discussed other challenges associated with incorporating industry partners into the school day. Speaking about a former partnership that dissolved, she explained how “it was logistically challenging with having to call in people from all different organizations and filling spots when people were sick and couldn’t make it.” The industry partner in her current program is large enough to deploy staff more flexibly, allowing for consistency in program content even if representing a different facet of the industry.

Learners benefit when partners understand how logistically complicated pathway programs can be for both industry partners and students as they balance other commitments. A student shared:

It was a little bit more difficult towards the spring because of [my sports schedule]. Once a month we had something usually at night. When we went to the [workplace], that was at night. I didn’t miss any type of schooling for that. … The shadowing I did during my school day. [The CTE center] gives me an excused absence for all my classes, so I got to catch up on work very easily at [school]. And then the [other activity] was right after school, so I did have to miss practice, but because it was an academic thing, it was not too difficult at all.

This story illustrates how students benefit when schools treat career connected activities as legitimate aspects of their education and work to accommodate logistical conflicts when possible. This recognition was reflected in the above student’s account of CTE work as “an academic thing” and part of their overall schooling, not something separate that created tensions with other priorities. Sites that serve adult learners may need to make different accommodations.

The above accounts show a consistent need for creativity and flexibility to make career pathway initiatives and partnerships effective for student and partner success. The participant viewpoints shared here illustrate only a few of the challenges in working across institutional boundaries—some of which can be envisioned at the outset while others will only be encountered during implementation. For example, another site initially used NHCF funding to provide gas cards for students but, due to the industry partner’s proximity, they largely went unused. This was an opportunity to flex their approach; instead, the site coordinators plan to request a budget adjustment for marketing materials to expand the program and reach more students.

The Importance of Exposure

Career pathway research has identified exposure as an important element in helping learners identify opportunities and refine their interests.26 Exposure is often enacted through one-time events like career fairs and guest speakers, and while these activities are constructive, exposure as a component of career planning should be thought of as a process that unfolds over time rather than a singular experience.

Career fairs and guest speakers can be useful for “getting them off on the right foot” and “to explore career pathways that you don’t always see in the core academics” as two different CTE directors put it. One of the Chambers involved in the study sites explained how they approach this phase of the exposure process:

We host a reception for students and their parents, and we invite some guest speakers from different health care organizations in the area to talk about what they do for a living, what they love about it, what’s challenging [about] their pathway, how they got to where they are.

Exposing learners to stories like this can support resilience and promote a sense of belonging if they perceive the storyteller to be like them and have encountered challenges they might anticipate.27

A different Chamber director explained the events they sponsor:

We would do kitchen tours with the culinary students or arrange facility tours with other groups. We also did the opposite of that, where we brought professionals to the high school to connect with students. … In the case of the computer science class, we bring in app developers and coders to sit side by side with the student—1:1 ratio or 1:2 ratio—and look at a project they’re working on and collaborate on that for an hour together. And then they would have lunch together afterwards and talk about what it’s like to work in tech full time and what are the positives and negatives of the career and the pathways to get to those careers.

One CTE director explained how meeting a diverse range of professionals is useful for “getting all those little pieces out there” regarding the nuances of jobs that may be obscured by what another respondent called “the big bucket jobs” like “a doctor or a teacher or a social worker.” The CTE director noted that students often don’t have a sense of the array of careers that exist, particularly beyond those outside of their own family or day-to-day experiences.

Career pathway exposure, therefore, partly involves connecting learners directly with people in jobs that might not be immediately apparent for individual students as they consider their options. One student described how this kind of exposure was essential for linking her childhood interests with her current ones:

I used to love Scooby Doo. I know obviously [this job is] very different from Scooby Doo, but that’s where it really piqued my interest in, you know, like mysteries. It’s evolved over time now. I’m more interested in why people commit crimes and the psychological side of things, versus the science-y side of things.

Career Exposure Opportunities Need Structure

Career pathway initiatives benefit from reciprocated structural elements embedded by both schools and/or community colleges with industry partners. Organizations who participate in collaborative career pathway programs to grow the workforce for their field should be prepared to arrange formative experiences across roles and tasks. This requires thinking through how engagement is organized. A CTE director explained how she “ran [another] program for three years begging [workplaces] to take students, occasionally getting one.” However, she continued,

… then it was just lackluster. There was no real structure to it; they would just kind of show up. If [students] saw something, they saw something. It needed some structure to make the [organization] comfortable with their participation. The idea of just having a high school student show up at their door five days a week wasn’t really appealing to them.

The necessary structure was finally enacted when a new workplace partner adapted an existing adult workforce training curriculum to suit youth under 18, which helped to organize student engagement around a familiar model. For their part, schools also must work to be clear about student expectations and standards in the workplace. One CTE director noted,

We do try to tread lightly and not add more work to somebody’s plate by having a student there. And our students are amazing; we do have a very tight, professional skill rubric they are expected to follow. They represent themselves well. I think that’s important in getting people out in[to] the community.

Structure along with the spirit of collaboration and organizational willingness to be creative and flexible relate directly to the quality of exposure for students and to the commitment to developing solid learning opportunities that build their careers.

Commitment to Learning

An important but sometimes overlooked dimension of the exposure process is supplementing career-connected learning experiences with information about the postsecondary options available in related fields. This dimension of career pathway programs is a clear and important distinction from general workplace onboarding: partners collectively commit to expanding learners’ options through further education. Credentialing organizations are indispensable partners in this respect, as one community college faculty member explained:

I’m trying to meet now with … eighth grade parents transitioning to high school, because once they’re in high school, you don’t get the parents. We’re trying to work at the eighth-grade level to talk to parents about pathways: “If you take these classes when you’re in high school here’s what dual enrollment can do for you.” And then use that as the opportunity to say, “consider a 2+2.”28

Hands-on Engagement

If exposure is the “shallow” aspect of a career pathway program, building robust opportunities for hands-on engagement provides depth. Learners need to test their emerging abilities firsthand as their interests develop. As one student said, “it’s really cool to get hands-on experience actually doing the things that we’re studying…That’s definitely my favorite part.” Hands-on engagement surpasses exposure as an opportunity to learn what it takes to succeed at a job: “A lot of our learning comes from mistakes,” a student noted, speaking about their past involvement in a manufacturing class. A different student also enrolled in the same class added,

I guess nobody likes bookwork. But I love going over and getting to use machines once we have everything down. And we’ve practiced it a couple of times because it takes a little bit to get used to it… some of them are manual, so you actually have to be precise with your handling of the machine.

The combination of mastering specific skills and learning through practical CTE or community college classes provides a linkage for students to think about their career goals through hands-on engagement that is grounded in real life experiences. A student in one of the research sites explained how the hands-on activities at the industry partner’s workplace helped her learn “what was really going on in the [workplace] versus just what like, television shows you or what you think, because it’s very different from, you know, the way social media portrays [people in this job].” Describing how the sustained exposure and hands-on experiences helped clarify their goals, the student continued:

[The class] was really what got the ball rolling for me. [Other classes] didn’t give me the opportunities that this class has given me. The class really set us all up for a real job in the work field—understanding what you were going to be doing versus what you may think you’re going to be doing or what you’re anticipating. It was awesome to not only get educated on these things, but finally see a real glimpse of how the [workplace] works and job opportunities that you don’t really think about before a class like this.

Industry partners also gain rewards from hands-on engagement as a crucial part of career pathway programs. “We try to get them … as hands on as we could possibly be,” one industry partner explained. Another described the value he receives in mentoring youth:

As far as like my inspiration for working with people, it’s an immediate reward. … If I sit there with three kids at a stove, and I’m on a cutting board and I’m teaching them the fundamentals of cooking, it’s always immediately gratifying and rewarding.

He further said that working side-by-side in a teaching capacity, with a wider view toward a student’s overall career development “differentiates our relationship with most employees. … It helps guide us to be the kind of mentors that we need to be for that student.”

Barriers and Future Needs

Program participants and partners acknowledged several barriers and future needs within the themes of:

- collaboration among willing partners

- overcoming obstacles through creativity and flexibility

- exposing individuals to careers they didn’t know existed

- helping them formulate clearer plans through hands-on learning

The barriers and future needs can be divided into two categories: internal to program functioning, and external relating to the wider state context.

Internally, NHCF funding enabled learners in each site to participate fully in their pathway program, from assisting with transportation to providing tuition scholarships and/or funding career fairs at a community college—whatever was needed at each local site. A comment from one CTE director captured the essence of this point when she said, “we are always looking to figure out how to break down any barriers that exist for students.” In this respect, NHCF funding affords flexibility that would otherwise be difficult to sustain. But money alone cannot fully alleviate the difficulties that exist when working across organizational boundaries.29 One CTE director described the struggle she faces in getting industry professionals involved in career pathway work more broadly.

Getting the industry to buy in [to the idea] that if you come sit on this committee for two times a year, which is all we’re asking, we really can expose your business and we can get you employees and things like that… I know everyone’s busy, but that’s one of our biggest struggles.

Conversely, a Chamber director described a challenge of working without educator buy-in. “It can be really tough if you don’t have buy in from the teacher. And if it’s not something that they are passionate about, or feel ownership of, it’s viewed as this extra headache.”

Cross-sector partnerships often include navigating organizational differences. At one of the sites multiple partners spoke about problems that arose due to staffing changes at the lead organization, when the main project organizer moved on. A teacher used the term “choppiness” to describe subsequent communication among the partners after the project manager left. The CTE director working on the same project noted that, “[The new coordinator] did a great job but he’s got so many other jobs too. That might have been a piece that was missing this year is having that one contact person to help coordinate.” These challenges point to the importance of achieving clarity around shared objectives, enrolling stakeholders who feel ownership of the program, and developing a communication plan that aligns with available roles and helps achieve sustainable coordination for the multiple project components.

Externally, respondents observed challenges related to the wider NH context including but not limited to concerns about resource parity across school districts. A Chamber staff member commented,

There’s a lot of disparities between different school districts in terms of what they’re able to offer their students. Like there are schools not far from [my city] that would benefit from connecting to [nearby] employers, but I just don’t know if that’s happening.

A different Chamber director broadened this concern beyond school districts to include collaborative efforts involving partners like his agency. Although the NHCF funding itself was straightforward to receive and helped catalyze a larger $350,000 federal grant, he explained some of the practical challenges involved with “braiding” funding from different sources,30 including long grant applications, bureaucratic challenges with receiving funding, and demanding grant reporting requirements: “it’s almost like a full-time job,” he said.

A CTE director at another site described the consequences of these conditions for schools and suggested how beneficial it would be to direct resources to grant writing support:

I think a lot of people don’t apply for some of these things because they don’t have grant writers in their district, and they don’t have experience; thinking from an equity perspective, putting resources out there so that folks feel supported.

The Chamber director who received the federal grant mentioned above stated bluntly that “the NH Department of Education needs to be more involved in career pathing,” a concern shared by a CTE director who wondered: “who’s going to recruit the next generation of CTE leadership? … Our credentialing process is pretty turbulent … People need to be thinking about how to support those folks.” One CTE director suggested schools may be limited in their ability to contribute solutions because of broader staffing constraints. A representative from a different Chamber expressed that a lot of CTE directors’ time is focused on relationship building and that “New Hampshire would really benefit from a more organized effort.”

In respondents’ views, such constraints in the education sector have repercussions for the wider economy. The director of a Chamber in a region that is economically dependent on tourist visitation recounted conversations with businesses in her area:

When I’m talking with the business community, I hear from so many of them that they’re stretched with their workforce. They don’t have staff and they’re challenged because their staff cannot find housing, or their staff has gone somewhere else because of other challenges. If we don’t have a strong front line, that’s going to impact our tourism.

Concerns about housing troubled another Chamber director even for professional jobs students might aspire to obtain:

[The] hospital has a heck of a time for certain positions that have to live within a certain drive to the hospital: You’re on a cath lab activation team, you have to live within a 10-minute drive of the hospital. Trying to find an affordable house to raise a family within a 10-minute drive of [the] hospital is a struggle.

The contextual challenges surfaced during the interviews for the present study suggest that many of the recommendations made in the 2009 Governor’s Task Force report are still relevant. For example, the report recommended creation of a student loan repayment program to encourage college graduates to remain in New Hampshire. A Chamber director spoke pessimistically about the prospects for this:

Some bigger picture stuff that New Hampshire just doesn’t do, like retaining young employees by offering to pay down some of their student loans. At some point, is the industry going to step in and start doing that for young employees so they can retain talent here in New Hampshire?31

Additionally, the 2009 report recommended establishing a program to “Engage and Empower Young Workers as Authentic Messengers” through career networking and media campaigns. Some progress has been made in this area, but efforts have been fragmented. One CTE director said,

We choose six stars that are seniors that have completed a program or will be completing a program. They explain how they chose it, why they chose it, and then what their next steps are … I think more of those statewide would be a great opportunity. … We actually contracted with a company to do nine 2–3-minute videos that identify that path in its entirety from starting the program to working in the industry. … I’m hoping those will help.

As mentioned previously, the existing IBuild NH program provides a good example of this kind of messaging campaign. Although such models are promising, they appear to be tailored to location- or sector-specific opportunities, motivations, and resources; the CTE director quoted above commented, “New Hampshire is very silo-based in general.” Future campaigns could benefit from a more systematic, statewide, multi-sector approach, particularly one that incorporates research-based insights into what works for an increasingly diverse population with potential interests in high-need career areas.

Discussion and Implications

Progress on Pathways, but Still a Way to Go

Apart from the insights these six sites provide into some of the nuances involved in making career pathway programs work successfully, they also reflect recommended elements of such programs generally. For example, the Pathways to Prosperity Project, a national model, recommends including the following “levers” in any program:

- a structured curriculum extending from high school into postsecondary education

- career awareness and work-based learning

- employer engagement

- intermediaries/brokers

- supportive policy such as dual-enrollment credits32

The stories recounted by interviewees add texture to understanding how relationships work across these roles. In the six cases studied here, Chambers of Commerce acted as key brokers between schools and businesses, community colleges provided structural links to the postsecondary level, and schools/industry partnered to organize specific learning experiences for youth leveraging the CTE structure. Respondents commented on how state policies both helped and hindered program implementation and expansion in ways consistent with issues identified more than a decade earlier in documents like the 2009 Governor’s Task Force report. In light of structural and policy gaps, funding provided by the NHCF—although relatively minimal compared to larger grant programs—was instrumental in anticipating participant barriers and helping partners adapt flexibly as conditions changed.

Implications: The Potential of Pathway Programs and Additional Policy Opportunities

The present study was not an evaluation, and its goal was not to make claims about program effectiveness. However, recent reports on larger-scale studies substantiate the value of pathway programs and should motivate further investment in programs like these. Two reports are especially noteworthy:

- A 2023 publication by the Gallup organization reports on a study of 9,641 New Hampshire middle and high school students regarding participation in career connected learning (CCL).33 Students who participated in at least one CCL experience were more engaged in school, hopeful about their futures, and clearer about their plans than students without CCL experiences. The number of CCL experiences had a positive linear relationship with engagement and hope, with 8+ experiences yielding the greatest benefit. Other factors that affected outcomes include adult mentorship and alignment between program offerings and student interests.

- A 2021 report from the Georgetown University Center for Education and the Workforce34 explains that 186,000 more youth would enter “good jobs”—those with a median salary of $57,000 by age 30—if they entered CTE programs in high school, with even greater increases for those who go on to pursue associates and bachelor’s degrees by age 22.

These reports provide strong evidence of current and future benefits related to career pathway involvement at the middle and high school levels.

Although this study set out to examine how collaboration supports career pathway programs internally, several conclusions can be drawn about how this work can be better supported at the policy and operational levels statewide.

- Regional coordination on career-connected learning opportunities would help alleviate the strain on individual schools, reduce duplication of effort, and fit within a “local control” funding paradigm.

- Students and industry alike would benefit from expanding youths’ access to career counseling resources, something that may not be achievable given the workload existing school counseling offices are managing.

- Partners across all sectors spoke of the benefit more centralized grant writing supports would provide. However, they also valued the continued availability of small, flexible, and easily accessed funding sources for meeting local needs.

- New Hampshire has adopted innovative business tax credit and wage match programs that provide financial support for businesses hosting high school apprentices.35 Not all respondents interviewed for this study knew about these programs, suggesting a need to advertise and evaluate them for potential continuation.

- Dual enrollment and early college credits are crucial elements of all career pathway programs. Expanding these programs in NH will require greater collaboration and integration across community college and University systems.

- NH RSA 186:11 IX-d, which governs the use of non-academic surveys in schools, could be modified to permit greater insights into students’ interests, career planning needs, and postsecondary plans. Current prohibitions prevent the effective collection and use of data to inform policy efforts.

Two final interview excerpts capture the state of the career pathway programs involved in this study, from both the organizational and student vantage points. The first, from a CTE director in southern New Hampshire, offers a global assessment: “I think we are shifting a little bit from ‘everyone has to go to college’ to ‘now there’s a lot of choices.’ But I don’t think we’re there yet.” The second, from a student, speaks to their promise: “I know that for me and a couple other friends … it helped us be able to graduate from regular high school because it gave us that push we needed.” It is likely that the language of career pathways and postsecondary education will rise in prominence against a higher education backdrop where college is likely to change in structure and value in the coming years, while also remaining culturally and economically important as New Hampshire strives to meet upcoming workforce needs. Further investment, expansion, and coordination of career pathway programs will extend gains to new populations and industry sectors seeking to locate to, and stay in, New Hampshire.

Endnotes

- Anderson, N. S., & Nieves, L. (2020). ‘College for all’ and work-based learning: Two reconcilable differences. In N. S. Anderson & L. Nieves (Eds.), Working to learn (pp. 1–22). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-35350-6_1

- Camoin Associates. (2023). State of New Hampshire Workforce Assessment Executive Report. https://www.nheconomy.com/getmedia/90db0638-52a5-4e4b-ba51-fd06719d30df/Final-Workforce-Assessment-State-of-New-Hampshire-v2.pdf

- Carnevale, A. P., Cheah, B., & Wenzinger, E. (2021). The college payoff: More education doesn’t always mean more earnings. https://cew.georgetown.edu/collegepayoff2021

- See e.g., https://cew.georgetown.edu/cew-reports/collegemajorroi/

- One example is Revision Energy’s Electricians Will Save the World program. See: https://www.revisionenergy.com/solar-company/solar-careers-and-training/electricians-will-save-world

- https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/20/podcasts/the-daily/is-college-worth-it.html?

- Carey, K. (2022). The incredible shrinking future of college. Vox. https://www.vox.com/the-highlight/23428166/college-enrollment-population-education-crash

- Hoffman, N., & Schwartz, R. B. (2017). Learning for careers: The Pathways to Prosperity Network. Harvard Education Press.

- Carnevale, A. P., Mabel, Z., Peltier Campbell, K., & Booth, H. (2023). What works: Ten education, training, and work-based pathway changes that lead to good jobs.

- World Population Review. (2023). Oldest states. Retrieved July 20 from https://worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/oldest-states

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2022). Residence and migration of all first-time degree/certificate-seeking undergraduates in 4-year degree-granting postsecondary institutions who graduated from high school in the previous 12 months, by state or jurisdiction (Table 309.30). The 59% is averaged across all the years these data are available. Vermont ranks first in the latest table but New Hampshire’s average percentage from 2012–2020 is highest in the United States. Institute of Education Sciences. Retrieved April 15 from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/current_tables.asp

- Pranger, A., Orrenius, P., & Zavodny, M. (2023). Texas natives likeliest to ‘stick’ around, pointing to the state’s economic health. https://www.dallasfed.org/research/economics/2023/0829?mc_cid=fdb1c02b33&mc_eid=7663262cb9 ; see also Johnson, K. M. (2023). Migration sustains New Hampshire’s population gain: Examining the origins of recent migrants (Regional Issue Brief #174). https://scholars.unh.edu/carsey/464/

- Sullivan, R. (2019). Aging and declining populations in northern New England: Is there a role for immigration? (Regional Brief). https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/new-england-public-policy-center-regional-briefs/2019/aging-and-declining-populations-in-northern-new-england.aspx

- https://www.nhcf.org/what-were-up-to/equitable-access-through-homegrown-career-pathways/

- Data retrieved from: https://netmigration.wisc.edu/

- https://www.stayworkplay.org/

- For a list of these programs, see: https://www.education.nh.gov/partners/education-outside-classroom/work-based-learning

- https://nhpbs.org/ibuildnh/. This program was partially funded by a small grant from the NHCF.

- https://cte.ed.gov/initiatives/career-pathways-systems

- https://careertech.org/cte

- https://www.education.nh.gov/who-we-are/division-of-learner-support/bureau-of-career-development/cte-programs-in-new-hampshire

- http://www.crdc-nh.com/tmap.html

- https://www.education.nh.gov/partners/education-outside-classroom/extended-learning-opportunities; https://www.nhelonetwork.com/

- https://extension.unh.edu/resource/nhs-workforce-youth-retention-initiative

- Michael Turmelle directs the Career Pathways Grant Program and consented to being identified in this report.

- Hoffman, N., & Schwartz, R. B. (2017). Learning for careers: The Pathways to Prosperity Network. Harvard Education Press.

- For a commercially available example of this, see: https://www.gladeo.org/career-navigation-platforms; see also Covarrubias, R., & Laiduc, G. (2021). Complicating college-transition stories: Strengths and challenges of approaches to diversity in wise-story interventions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, Advance online publication, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916211006068

- 2+2 programs are arranged to facilitate students earning an associate degree at a community college then transferring to a 4-year institution to complete a baccalaureate degree.

- Star, S. L., & Griesemer, J. (1989). Institutional ecology, ‘translations’ and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–39. Social Studies of Science, 19, 387–420.

- On recommendations for “braiding” funding, see: https://cte.ed.gov/initiatives/career-pathways-systems

- For a recent story on this, see: https://hechingerreport.org/aging-states-to-college-graduates-well-pay-you-to-stay/

- Hoffman & Schwartz (2017).

- https://nhlearninginitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Gallup-New-Hampshire-Learning-Initiative_-Report_2023.pdf

- Carnevale, A. P., Cheah, B., & Wenzinger, E. (2021). The college payoff: More education doesn’t always mean more earnings. https://cew.georgetown.edu/collegepayoff2021

- https://www.education.nh.gov/partners/education-outside-classroom/work-based-learning. See: Work! As Learning and Career and Technical Education Tax Credit.

About the Author

Jayson Seaman is an associate professor and chair of the Department of Recreation Management and Policy, as well as a Carsey Faculty Fellow, at the University of New Hampshire.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge the study’s participants for contributing their time, the members of the New Hampshire Youth Retention Initiative research team—Cindy Hartman, Andrew Coppens, Kate Moscouver, and Hannah Falcone—for their input on research design and analysis, and the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation for supporting the project financially. Any errors or omissions are the author’s responsibility.