Key Findings

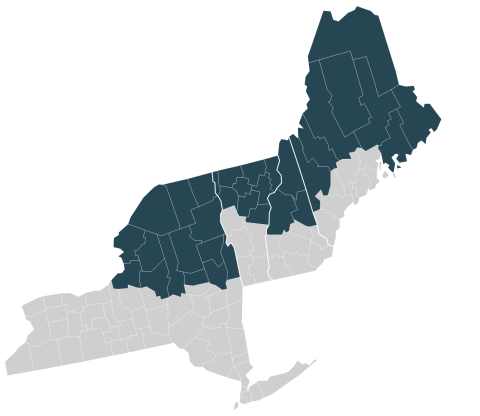

The Northern Forest—a 34-county swath of northern Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, and New York—has long attracted tourists for its outdoor recreational amenities1 (see Figure 1). With a recreation-heavy economy, the region traditionally serves seasonal skiers and hikers with an expansive mix of short-term rentals and second homes.2 This combination of rural features and occasional-use housing took on special meaning at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic when as early as April 2020, popular media began to report a pattern of urban residents fleeing cities to take refuge from Covid-19 in these amenity-rich rural regions.3 For instance, New Hampshire Public Radio reported that metropolitan residents were “hunkering down” in second homes in northern New England,4 and later research confirmed a shift from temporary and seasonal stays to permanent residence changes.5

In the intervening years, more data have become available, and it is easier to document the extent of these shifts. The Northern Forest did indeed see an increase in domestic migration in the pandemic era, with 85 percent of the region’s counties experiencing domestic in-migration gains between 2020 and 2021, compared with 63 percent of counties in the rest of the United States. However, the details of these moves remain less documented: who moved to the Northern Forest region, and why? Do they intend to stay? And what does that mean for those who already lived there? This research brief shares findings from interviews with 16 such movers (and six regional real estate agents), conducted in spring 2023 as part of a larger project documenting Covid-era migration in the region. While the project was spurred by the pandemic, findings can support community stakeholders in understanding characteristics of migrants and features that attract them that will be useful in future waves of migration, for instance, in response to climate change or Baby Boomer retirements.6

Figure 1. Northern Forest Region Locator Map (shaded)

Source: Carsey School of Public Policy map, created in Datawrapper, using information from the Northeastern States Research Cooperative.

What made you choose the Northern Forest?

To supplement information available through existing data sources, interviewees were asked to describe why they chose to move to the Northern Forest region. With the region’s access to mountain ranges, lakes, the Atlantic coast, and undeveloped forestland, it is perhaps unsurprising that the most-mentioned factor was the region’s landscape and its “beautiful pristine wilderness.” Participants described “the terrain” and “the fact that we had so much nice nature right near us” as influencing their choice.

Aside from the vistas, movers also connected the Northern Forest’s landscape to enhanced opportunities for outdoor recreational activities, with special appreciation for the breadth of options offered in the region. Interviewees mentioned hiking, rock climbing, skiing, swimming, waterskiing, boating, and sailing as part of their interest in moving to the Northern Forest. One explained that “access to skiing” was a “requirement” when deciding on a location to which to relocate their family. For others, the volume of opportunities played a role: “I am able to, from a five-minute drive from three directions of my apartment, go for some of the most beautiful hikes I’ve ever seen,” said one interviewee.

“Privacy, quietude, serenity are what kept drawing me to come back again and again.”

Connected to the region’s physical features, half of the interviewed movers listed the region’s rural character and low population density as attractive. Some wanted to live somewhere “a little quieter” where they did not have to interact with people, like the participant who described themself as “not a big people person” and said they would “prefer to see moose and bears [rather] than humans.” One resident called the region one of their “dream places,” describing themself as “that guy who wants to live in a cabin in the woods—a hermit with an internet connection.”

Box 1. Where did interviewed movers come from?

Eight of the 16 interviewed movers shared that their prior residence was in the Northeast, but outside the Northern Forest region. This distribution generally aligns with the origins of movers documented through data available from the Internal Revenue Service, drawing on changes of address associated with tax filings, which suggests that 48 percent of movers into the Northern Forest came from elsewhere in the Northeast.7

For others, however, the enthusiasm for rurality was paired with practical considerations about access to city-based amenities as needed. The region’s reasonable distance from more urban areas like Boston, Portland, or New York City was regularly referenced and important in conjunction with its rural context. One interviewee named “the combination of the rural aspects of it while still having cities that have things to do” as key.

“I wanted something smaller, where I could actually be part of a community.”

Intertwined with the potential solitude of rural spaces, interviewees also recognized that they had moved to small communities that could foster neighborliness, albeit in ways specific to “the Northeaster[ner] personality.” “There’s definitely a friendliness and people will help out their neighbors, but there’s also a ‘doing your own thing’ [mentality], and you can just kind of be independent and keep to yourself if you like. That’s what we’re looking for.” Others hoped to develop deeper connections with time: “I was looking for a small community where we would be able to get to know people, where you would bump into people that you knew at the grocery store, where you could become a useful part of a group instead of just one more faceless person.”

At the same time, at least one interviewee sensed some local skepticism about their commitment to the community. “I think people still expect that I’m going to leave. They give me that look like, ‘…here’s a kind of crazy person from the city who’s up in the neighborhood, and he’s not the first one I’ve seen in the past three years.’ There’s kind of that vibe a little bit.” Potential for tension between newcomers and “old-timers” has long been documented in amenity-rich rural regions, especially around priority setting within the community.8

Did the pandemic drive migrants to the Northern Forest?

For most interviewees, the pandemic was not a primary driver of their move to the Northern Forest. Very few people explicitly referenced a reduced risk of infection as playing a role in their decision to move. Rather, the pandemic more often functioned as the impetus for a move that interviewees were already considering. For example, half of the interviewees explained that once the pandemic started, their job shifted to remote work, allowing them to “live wherever [they] wanted as long as [they] had a relatively good internet connection.” One participant said they and their spouse “did research for a couple of years” before they purchased their house once they could afford it. Another started “taking some trips” to visit the area in 2018 before moving in mid-2020; “working probably 15-, 16-hour days seven days a week” during the pandemic allowed them to purchase a home with the overtime pay earned. A third participant explained that the pandemic was part of their motivation to be closer to aging family in the region.

“In a way, we’re home…We see ourselves growing old here and being here forever.”

By and large, the movers we interviewed planned to stay in the region for good. Several interviewees said they had been dreaming about living in the Northern Forest for years—including one who “fell in love with the area probably when [they were] two years old” on a family visit. At the other end of the spectrum, one interviewee purchased a house in the Northern Forest region though they had “never even been to New England.” Regardless of how long they considered their relocation, most movers planned to stay in the region forever. “The goal is that this is the forever home, the move to end all moves,” one said. Another insisted, “You’d have to drag us out.” For those who did not intend to stay forever, life course transitions like military duty and college graduation played a role, as did a lack of job opportunities in the region.

Real estate agents’ perspectives: “I think that most of the people who came here had a relationship here.”

To get a wider perspective on migration into the region in the pandemic-era period, we also interviewed six Northern Forest real estate agents. Agents were asked to describe their sense of Northern Forest home buyers and desirable real estate features in the early period of the pandemic. Across the board, agents suggested that the housing market had intensified during the pandemic, although Covid was not the only driver. One Maine real estate agent described, “There were a lot of people who came from the cities and fled here to get away from the pandemic in the beginning.” A Vermont counterpart had a similar experience, noting “We had a large population of first-time home buyers. We also had a huge wave of folks coming over from out-of-state, particularly from New York…I feel like people who had families definitely wanted to get out of there. A lot of the people from New York were families, young professionals.”

There was a sense among real estate agents that movers did not select the Northern Forest region at random. One agent noted, “I think that most of the people who came here had a relationship here. Either they had vacationed here or they had a family house here…there was some sort of connection to this area.” For others, Covid-era migration was part of a broader context of migration into the region. A New York agent commented, “We call them climate refugees…people coming from the West Coast are escaping drought and forest fires and smoke and that kind of stuff.” In the pandemic context of growing remote work, however, “one of the first questions out of their mouths was ‘is there high-speed internet?’” In addition, many of the real estate agents’ observations overlapped with what movers described—for example, that migrants were attracted to the natural beauty of the area.

Quantifying higher-income movers

The real estate agents we interviewed also identified some potentially worrisome impacts connected to the recent wave of migration. In particular, interviewees pointed to skyrocketing home prices connected to a broader context of demand, particularly among high-income movers. “That house that used to be $180,000 that Joe Blow Local could buy is now $300,000 or $400,000. That’s a big, huge jump. Now for the summer person who’s buying it, that’s nothing. They buy it and they fix it up…That obviously is having a negative impact on affordable housing.” In addition, movers who purchased a second home without selling their prior residence were identified as exacerbating a broader lack of real estate inventory.

Agents’ impression that in-migrants were disproportionately high income aligns with Internal Revenue Service (IRS) data from this period. By matching addresses of tax filings in 2020 and 2021, IRS data document inter-county moves, and allow us to identify some income details about Northern Forest movers. We find that in 29 of the Northern Forest’s 34 counties, in-migrants had higher per capita adjusted gross income than existing residents, and in some cases, that gap was extreme. Figure 2 shows the top five counties where these income gaps are the largest (in terms of percentages).

The gap between newcomers and existing residents was most significant in Carroll County, New Hampshire, where in-migrant income exceeded locals’ income by 84 percent (about $95,000 versus $52,000). While higher-income residents can bring new resources to the region, there is a risk of intensifying pressure on local workers and residents through the housing market or demand for expensive services. On the other hand, while lower-income movers do not risk driving up housing prices in the same way, these newcomers may have additional needs that local communities are unprepared to meet. In-migrant income was only lower than existing residents’ income in six counties (Jefferson, Oneida, Herkimer, and Oswego Counties in New York, and Penobscot and Somerset Counties in Maine). However, four of these counties had substantial (top 10) numbers of in-migrants, suggesting that the challenge is not an insignificant one for the region.

Figure 2. Per Capita Income in Northern Forest Counties with Largest Gap Between In-Migrant and Existing Resident Income

Note: “Per capita income” is per capita adjusted gross income (AGI). “Largest gap” is defined as the percent difference between in-migrant and existing resident per capita AGI. IRS Statistics of Income (SOI) data include tax filers only; not all individuals are required to file an individual income tax return. Movers are filers whose 2021 tax filing (regarding income earned in 2020) had a different mailing address than their 2020 tax filing (regarding income earned in 2019). Because the address used for matching is a mailing address at filing time, it may not reflect the taxpayers’ location at the time the income was earned.

Source: Carsey School analysis of IRS SOI 2020–2021 data.

What can Northern Forest communities learn from pandemic-era migration?

First, stakeholders in the Northern Forest region are no strangers to recognizing, stewarding, and amplifying the region’s natural beauty. Recreation and tourism driven by the region’s stunning landscapes and outdoor recreation opportunities have long been critical economic engines of the region, and those concepts resonated intensely with the movers we interviewed. Other research has documented the importance of both the natural environment and its proximity to more urban areas, which remain important here.9

The region’s ability to attract residents is unlikely to end with the pandemic. Conversations around climate migration have continued across parts of the region, with questions about whether and how communities develop a plan to accept potential future waves of migration at the forefront.10 Understanding the potential strains on community infrastructure, from housing stock to sewers to internet, helps communities plan ahead. Planning efforts can be further guided by the awareness that newcomers likely intend to stay long-term, which may help justify additional investments in infrastructure expansion.

Second, most Northern Forest communities saw an uptick in domestic migration during the pandemic, and incoming migrants more often had higher incomes than locals. How might newcomers be brought into the fold of communities they intentionally sought out, and use their positions of relative advantage for local good? At least at the highest level, our interviewees described themselves as valuing many of the same things that long-time Northern Forest residents seem to: the region’s clean, rugged landscape; opportunities to enjoy the outdoors through sport and recreation; nearness to family; neighborliness and privacy. Identifying ways to leverage shared values and plan for sustainable community growth is a next step.

This brief draws on 22 semi-structured interviews conducted for the qualitative portion of a mixed-methods study on migration into the Northern Forest (UNH IRB-FY2022-395). Data were collected in spring 2023 and included six Northern Forest region real estate agents and 16 individuals who had moved into the Northern Forest region since March 2020 (“movers”). Movers were split across the Northern Forest in Maine (3), Vermont (4), New York (5), and New Hampshire (4), and real estate agents served one or all of the states that make up the region.

Movers were recruited through an online convenience sampling approach, via Reddit posts describing the study shared on targeted subpages (subreddits) focused on the region. Purposive sampling was utilized to recruit real estate agents, who were reached via publicly available contact information associated with real estate groups serving the Northern Forest region. All interviewees were compensated with a gift card for their participation.

Interviews were conducted by Zoom or by phone, with the recorded portion lasting an average of 17 minutes and, using a semi-structured interview guide, tailored to real estate agents or movers. With participant consent, interview audio was recorded and later machine-transcribed before being edited for accuracy. Quotes used here may be edited to protect the identity of participants, such as removing or changing a specific town name. Transcripts were analyzed using Dedoose software. Because interviews were semi-structured, initial deductive codes were developed based on the interview instrument questions, with additional inductive codes emerging based on topics or themes which arose organically during the conversations as analysis continued.

- Northern Forest Center. 2023. https://northernforest.org; Economic Research Service. 2017. “County Typology Codes.” Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/county-typology-codes.

- Bailey, Adams Nicholas. 2022. “Municipal Short-Term Rental Policies: Analysis and Recommendations for Adirondack Communities.” Master’s Thesis. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University. https://northernforest.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Short-Term-Rentals-in-the-ADKs.pdf.

- Ropeik, Annie. 2020. “Locals Bristle as Out-of-Towners Fleeing Virus Hunker Down in New Hampshire Homes. NH News, April 2. Concord, NH: New Hampshire Public Radio. https://www.nhpr.org/nh-news/2020-04-02/locals-bristle-as-out-of-towners-fleeing-virus-hunker-down-in-new-hampshire-homes#stream/0; Stephens, Kay. 2020. “The Impact of COVID-19’s Urban Flight on Mainers.” September 9. Penobscot Bay Pilot. https://www.penbaypilot.com/node/137406; Urquhart, Adam. 2020. “Affluent Out-of-State Homebuyers Look to New Hampshire for Escape.” November 6, The Keene Sentinel. https://www.sentinelsource.com/news/local/affluent-out-of-state-homebuyers-look-to-new-hampshire-forescape/article_3ca0fb6c-e9c3-5c34-b2f2-64117c75af12.html.

- Ropeik, 2020.

- Chiumenti, Nicholas. 2021. “How the COVID-19 Pandemic Changed Household Migration in New England.” New England Public Policy Center Regional Briefs 21-3. Boston, MA: Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/new-england-public-policy-center-regional-briefs/2021/how-the-covid-19-pandemic-changed-household-migration-in-new-england.

- Hurdle, Jon. 2022. “As Climate Fears Mount, Some in U.S. Are Deciding to Relocate.” Yale Environment 360, Marcy 24. New Haven, CT: Yale University, Yale School of the Environment. https://e360.yale.edu/features/as-climate-fears-mount-some-in-u.s.-are-deciding-to-relocate; Ropeik, Annie. 2021. “Americans Are Moving to Escape Climate Impacts. Towns Expect More to Come.” Special Series: Environment and Energy Collaborative, January 22. Washington, DC: National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/2021/01/22/956904171/americans-are-moving-to-escape-climate-impacts-towns-expect-more-to-come.

- Authors’ analysis of Internal Revenue Service Statistics of Income 2020–2021.

- See, for instance, Hamilton, Lawrence C., Leslie R. Hamilton, Cynthia M. Duncan, and Chris R. Colocousis. 2008. “Place Matters: Challenges and Opportunities in Four Rural Americas.” Reports on Rural America 1(4). Durham, NH: Carsey Institute. https://scholars.unh.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1040&context=carsey.

- See, for instance, Bundschuh, Kristine and Kenneth Johnson. 2023. “Retaining Residents Is Important to New Hampshire’s Future.” National Issue Brief No. 172. Durham, NH: Carsey School of Public Policy. https://carsey.unh.edu/publication/retaining-residents-is-important-to-new-hampshires-future.

- Hoplamazian, Mara. 2023. “Climate Change Could Drive Migration to New England. Some Communities Are Starting to Plan.” By Degrees, May 18. Concord, NH: New Hampshire Public Radio. https://www.nhpr.org/nh-news/2023-05-18/climate-change-could-drive-migration-to-new-england-some-communities-are-starting-to-plan.

This project was supported by the Northeastern States Research Cooperative through funding made available by the USDA Forest Service. The conclusions and opinions in this paper are those of the authors and not of the NSRC, the Forest Service, or the USDA.

- Jess Carson is the director of the Center for Social Policy in Practice and a research assistant professor at the University of New Hampshire’s Carsey School of Public Policy.

- Sarah Boege is a senior policy analyst with the Center for Social Policy in Practice at the Carsey School of Public Policy.

- Libby Schwaner conducted this work as part of her role as a policy analyst while at the Carsey School of Public Policy.