Project Readiness Questions

- What are the basic financing structures for LMI community solar?

- How do you build a basic financial model to reflect your solar project?

- From the funder perspective, what makes a “good” or “bad” solar project?

- How do you determine if you need gap financing or grants to make your project viable?

Background

Becoming an LMI Community Solar developer requires a fundamental understanding of financial structuring. This chapter provides a brief introduction to solar equipment finance and lays the groundwork for you to begin building your own financial models.

Once solar developers work with solar installers to determine the upfront cost to build their projects, they must find the sources of capital to cover the upfront costs. Most upfront capital contributed to solar projects must be paid back over time throughout the operation of the project. These sources are provided with an expectation of a minimum investment return. Initial investment returns for all sources are projected in financial models at the beginning of projects and then it is up to solar developers and operators to ensure the projects perform to certain expectations and repay capital providers. For LMI community solar projects to be considered financially successful and for developers to earn repeat business, projects must provide both the meaningful community benefits included within and exceed initially projected returns for all capital providers, which is calculated in the returns tab of the financial model.

In order to understand LMI community solar finance, it is critical to first learn standard community solar finance. This is because both financing models are functionally the same. They both require upfront capital for construction, reliable ongoing revenue sources, dollars to fund operating expenses, and then cash distributions to pay back owners and investors for providing upfront capital. The LMI Community Solar finance structure just adds a financing layer for LMI benefits. Before you become an expert at providing LMI benefits in your solar projects, you must first learn how to balance upfront costs against ongoing cash distributions to meet owner and investor return expectations.

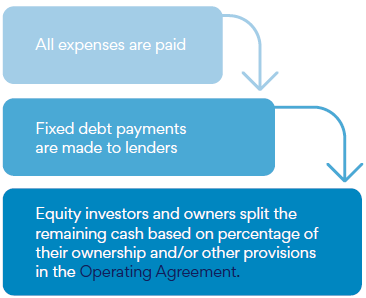

Upfront capital to fund solar projects can come in two main forms—equity and debt. The difference between equity and debt is that equity is paid into a project in exchange for a share of ownership and cash flows, while debt does not include ownership. Debt is paid into a project in exchange for a fixed repayment during operation. The sequence of debt and equity repayment is defined in a project’s Operating Agreement. Generally, the revenues received by a solar project are paid in a sequence of payments called the “cash flow waterfall,” which typically looks like this:

Tax equity and grants are considered other forms of equity that are used to finance the upfront cost of community solar. These sources are very critical for LMI Community solar developers because they generate more cash for construction, but this cash does not need to be paid back with the revenue made during operation, which allows for more benefits to go to LMI customers. Tax equity is cash paid into a project by an investor in exchange for the right to own certain tax certificates that are generated by the development of solar projects. Tax equity investors receive their returns in the form of tax benefits and not cash from operations.

Grants are cash paid into a project in exchange for a certain social good. For example, a foundation might make a grant to a project to provide discounted solar power to low-income households. As long as projects provide these social goods for agreed upon periods, the developer does not repay the cash received through the grant.

A deferred developer fee is another potential source of equity for a project. Deferred developer fee is money charged to a project by a developer that is not paid upfront, but instead is left in the project until the project has been completed and is instead paid from project operating.

Sponsor equity is the last potential capital source, which comes from the project developer’s own contribution of capital from concept through start- up and operation. This investment is the highest-risk capital because it gets paid back last after all other sources.

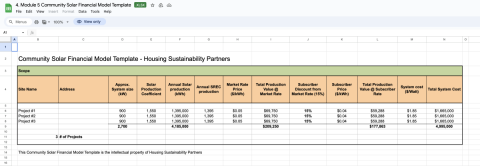

A financial modeling template is a tool used by developers during the development process to create a financial plan for a project. It provides a framework for estimating the costs and revenues of a project over its lifetime, as well as the potential risks and returns associated with the investment. Community Solar Financial Modeling entails gathering and organizing a set of technical and financial assumptions to tell a story about how upfront costs of projects are funded, how specific sources of capital are allocated to specific upfront costs, and how much revenue and expense a project will incur during operations.

A good financial model should include a project scope, sources and uses, loan terms, an annual operating budget, year over year revenue and expenses, as well as a sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of different variables on the project's financial performance. There are many templates and calculations that can be added to community solar financial models, but all financial models should lay out the following information and calculations:

Project Scope – An overview of all the technical assumptions about your project, such as project location, size, anticipated performance, power value, energy savings, etc.

Sources and Uses – An overview of the upfront expenses necessary to complete the installation of a project and the upfront sources that will be used to fund all expenses.

Loan – Upfront loan amount and agreed upon repayment terms are input to calculate an ongoing payment amount during operations.

Proforma – A year over year calculation of the ongoing revenue and expenses for a project. The template includes an expectation of the amount and timing of repayment for equity investors.

Grants/Incentives – A template used to calculate an upfront grant that can be used as a source of ongoing incentive that increases operating revenue.

There are several financial modeling templates available online that can be used as a starting point, such as those provided by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) or the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA). What is most important is that you clearly understand the financial model and explain all your assumptions and results. The template provided in this workbook was created by Housing Sustainability Advisors and adjusted over ten (10) years of trial and error. You will notice that it is simpler than most other financial modeling templates available. This simplicity is intentional to keep the developer focused on the primary factors determining project financial success and to manage project risks. The template can be customized to fit the specific needs of the project and to reflect the unique assumptions, costs, and revenue streams associated with community solar development.

The upfront capital costs required to build and set up the project for operations, also referred to as “Uses,” can be separated into the following buckets:

Construction costs: These include costs associated with installing solar panels and other equipment, as well as labor costs.

Site Acquisition costs: These include costs associated with securing site control.

Permitting and regulatory costs: These include engineering and fees for obtaining permits and complying with regulatory requirements.

Financing costs: These include fees and interest charges associated with obtaining financing for the project.

Administrative, legal, accounting costs: These include costs associated with setting the business structure, negotiating funder agreements, and financial accounting.

A customer subscriber agreement is a contract between a solar energy provider and a customer that specifies the price at which the customer will purchase electricity generated by the solar project over a defined period. Forecasting the subscriber rate for a community solar project can be a complex process that involves using different methods such as comparing the customer rate to utility prices, using a calculator provided by a utility, or forecasting wholesale energy prices. A subscriber rate for solar electricity can be fixed or floating. A fixed rate means that the price remains constant throughout the contract period, while a floating rate means that the price varies depending on standard utility energy rate. The customer rate can also have an escalator clause, meaning that the rate increases over time, usually in line with inflation or other predetermined factors.

The subscriber rate for a community solar project should be estimated as early as possible in the development process. It is critical to have an accurate estimate of the subscriber rate in order to determine the financial feasibility of the project and to secure financing. The subscriber rate is typically estimated during the project planning phase, after the solar developer has conducted a preliminary assessment of the project site, evaluated financing options, and determined the expected energy output of the project. This information is used to develop a preliminary subscriber pricing model and estimate the rate.

As the project progresses through the development stages, the solar developer will continue to refine the subscriber rate estimate. For example, as more detailed engineering and construction plans are developed, the solar developer may be able to refine the project costs, which will in turn affect the subscriber rate. As the project moves closer to construction, the solar developer may also be able to secure more detailed financing terms, which will also impact the subscriber rate.

If applicable in your locality, Renewable Energy Credits (RECs) should be included in revenue sources, estimating the price that the project will be able to sell any RECs it generates, as well as any income the project may receive through participation in state renewable energy credit programs.

With Community Solar, Operating Revenue refers to the income generated by the project's energy production and sales, typically through contracts with LMI customers. Revenue can be calculated by multiplying the energy produced by the project by the agreed-upon rate, also referred to as the Subscriber Rate or PPA rate. .

To generate a positive return on investment, community solar developers must make accurate estimates upfront regarding future ongoing operational costs. While operational upkeep is typically minimal for solar energy installations relative to real estate assets, solar owners must be prepared for occasional part failures, fixes, and replacements. Below are the typical operating expenses that you should prepare for:

Operations and maintenance costs: These include hiring a vendor to perform ongoing monitoring and maintenance on the solar system, as well as any necessary repairs.

Insurance and taxes: These include costs associated with insuring the project and paying property taxes.

Marketing and outreach costs: These include costs associated with promoting the project and attracting subscribers.

Site Lease: This includes any payment made to the land owner for the right to continue operating the solar facility on the site.

Administrative and legal costs: These include costs associated with managing the project and complying with legal requirements.

Subscription management: These include payments made to the vendor managing the customer subscriptions and invoicing for the project.

Operating capital: Operating capital refers to the funds that a project company has available to finance its day-to-day operations.

By knowing operating expenses and exactly how much energy is going to be produced by a project, solar owners can then weigh total expenses against revenue and ensure long-term profitability.

With solar project financing, lenders may require either collateral and/or guarantees to mitigate the risks associated with projects, providing additional layers of protection against loan defaults. Collateral refers to any property or assets that a borrower pledges to a lender as security for a loan. In the context of solar project financing, the collateral typically refers to the solar panels and equipment that will be used to generate revenue, the project's actual revenue, and/or the project's real estate. The collateral serves as a protection for the lender, as they can seize and sell the assets if the borrower defaults on the loan. Or it provides lenders with a source of repayment if the project fails to generate enough revenue to pay off the loan.

In addition, lenders may require developers to provide guarantees to secure financing. Guarantees provide lenders with assurances that a third-party will step in to repay loans if the borrower defaults. These guarantees can be in the form of personal guarantees or corporate guarantees. Often, guaranteed loans have better terms and are easier to close because they are much less risky for lenders. Yet, a company’s assets must be quite high for a lender to accept a guarantee. Pledging collateral is the most common form of lender security required, while guarantees are much less desirable to borrowers and less typical. Collateral and guarantees provide lenders with a greater level of security and increase the likelihood of lenders making loans.

Action Items

- Gather solar energy production assumptions from installer and/or solar design software tools. For a more in-depth explanation of solar resources, check out this PowerPoint.

- Assumptions include site names, addresses, solar system sizes (KW), annual solar production potential (kWh), upfront system cost, utility power rates ($/kWh), community solar value ($/kWh), subscriber purchase price ($/kWh), and environmental attributes generated.

- Reach out to local vendors to determine upfront project development and installation costs. Solar is priced based on $ per Watt. Community solar pricing across the country ranges from $2/Watt on the low end to $4/Watt, depending on local labor rates and installation type (i.e., rooftop, ground mounted, carport canopy, etc.).

- Size development fee between 10-20% of total project costs, depending on how much the project can afford.

- Calculate tax equity generated. For more information on the tax credit, please see Tax Equity Investor term Sheet and the Novogradac Renewable Energy Tax Credit Resource Center. Please note that the authors are not tax professionals. Before making accounting or tax decisions, consult a certified accounting professional.

- Reach out to lenders to determine basic loan terms.

- The loan amount must be sized to a payment amount on the proforma template that is not less than 85% of the Net Operating Income, or 1.15 Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR).

- Use the incentive template to calculate any upfront or production-based grant amounts.

- Ensure the sources match the uses and the gap/surplus is zero. If sources and uses do not match, and there is a gap, then you will have to find another grant or contribute Sponsor equity.

- Include a strong contingency against escalating costs during installation. Five (5) percent of hard cost is a small contingency. Fifteen (15) percent is probably too high. The higher the contingency, the harder the project is to finance upfront, but over the long run it reduces significant stress and further ensures project success.

11. Reach out to lenders to get indicative loan terms for your project. You must get at least the maximum loan amount, interest rate, term, and minimum. For more detail on the indicative loan terms to gather, see the Debt Due Diligence Template and Debt Term Sheet Template.

Research all available grants and incentives for your project. State solar incentives are usually sized based on project size. Use the “Incentives” tab of the financial modeling template to perform any necessary calculations to determine the grant size.

- Reach out to vendors and confirm expense assumptions are correct.

- Ensure any loan is sized to the proper debt coverage ratio.

- If a solar company is a taxable entity, ensure the project has enough cash flow to pay taxes.

- Check that equity investment sections are working correctly and the cash flow is sufficient to repay equity. You should be projecting above a 10% Internal Rate of Return (IRR) on equity invested into the project.

- If IRR is considerably above 10%, then you may make more cash available to reduce the price of power for sale to LMI customers.

Does Your Deal "Pencil Out?"

Penciling out is a term that developers use to refer to whether a deal makes financial sense or not. They typically measure whether a deal pencils out in the following ways:

- Internal Rate of Return (IRR) - good is between 10%-20%.

- Annual Cash on Cash Return - Should be over 8% hurdle rate. A hurdle rate is the minimum rate of return required for a company or investor to move forward on a project. Most companies factor in a risk premium when determining their hurdle rate, assigning a higher rate to riskier projects and a lower rate to projects that present more moderate risks.

- Total Cash Flow – there is no magic number here. It’s whatever amount the developer feels like is worth the time and risk.

- Payback period – Refers to how quickly your initial equity is returned. Most developers are interested to know the point at which their initial investment has been returned and they are earning money beyond that.

Take Note: Tax Equity Changes from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)

On Aug. 16, 2022, President Joe Biden signed into law the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA), which includes new and revised tax incentives for clean energy projects. This resource is a summary of a resource provided by Novogradac on the IRA impact on tax credits for community solar, which were extended and significantly expanded. Please note that the authors are not tax professionals. Before making accounting or tax decisions, consult a certified accounting professional.

Tax Credit Bonuses

- Low-income bonus -- Additional 10% to 20% for low-income projects

- Energy Community Bonus: +10% Investor Tax Credit (ITC) bonus for three types of sites -- Brownfield sites, a.k.a. Superfund, Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) in coal, oil, or natural gas industries with unemployment higher than the national average, or Census tracts where a coal mine or coal-fired electric generating unit closed

- Domestic content bonus: +10% ITC Bonus – Steel and Iron – All steel and iron manufacturing processes must be in the U.S. and Manufactured Products – A set percentage of the total costs of all manufactured products within a facility are attributable to manufactured products in the U.S.

Direct Pay For Nonprofits

If an applicable entity makes a direct pay election, the amount of the tax credit is treated as a deemed payment of tax, which for a not-for-profit entity without taxable income, results in a cash refund payable by the government. Direct pay is only available to rural electric cooperatives, municipal utilities, and other tax-exempt entities such as local and Tribal governments.

Transferability

The IRA made Solar Investment Tax Credits completely transferable to another unrelated taxpayer, which opened the market for solar tax equity to many other tax equity investors and made deal structuring easier and less expensive.

Eyes on Equity

The key to unlocking more benefits for LMI communities through financial modeling and structuring lies in your ability to find sources of capital that do not require repayment from the cash flow waterfall. The cash flow waterfall refers to the order in which cash flows are distributed and paid back among various stakeholders in a project.

Typically, in a solar project, the first priority for cash flow distribution is debt repayment, followed by returns for equity investors, and then any remaining cash flow is distributed to other stakeholders, such as community members. If sources of capital are identified that do not require repayment, such as grants or tax credits, more cash flow becomes available for distribution to lower the cost of community solar subscriptions and pass on more savings to LMI customers.

Learn more about: Project Finance for accelerating LMI Solar Access

Additional Resources

- Unlocking Solar for Low- and Moderate-Income Residents: A Matrix of Financing Options by Resident, Provider, and Housing Type: this NREL guide provides a matrix of financing options for LMI community solar projects for different housing types.

- SUNDA Project – a financial modeling tool from the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association (NRECA) for rural electric cooperatives developing community solar.

- Determining Solar costs – U.S. Solar Market Insight Report and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory’s annual update of utility-scale solar data and trends.

- Join the Community Power Accelerator: Powered by the U.S. Department of Energy, the Accelerator provides training, technical assistance, and bridges the gap between solar projects that need funding, and lenders who want to finance them, expanding access to affordable solar energy