LOW-TO-MODERATE INCOME (LMI)

Community Solar Developer Workbook

National Community Solar Partnership

Community Power Accelerator

This workbook was developed by Housing Sustainability Advisors and the Center for Impact Finance at the Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire. This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) under Solar Energy Technologies Office (SETO) Agreement Number 36483 and Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231.

The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Energy or the United States Government.

Note: Text formatted bold links to documents created as content for the Community Power Accelerator Learning Lab; text formatted blue links to external resources; and text formatted Gray are key terms that link to definitions in the “Key Terms” section of the Appendix.

Introduction

This Workbook provides tools and advice to guide developers of community solar projects that benefit low-to-moderate income (LMI) households. While solar project development and finance is complex, all projects share a common set of steps and strategies that will be covered throughout this Workbook.

The Workbook is part of the Community Power AcceleratorTM (the Accelerator), which connects developers, investors, philanthropists, and community-based organizations to finance and deploy equitable solar projects across the country. U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) National Community Solar Partnership (NCSP), the Accelerator provides training, technical assistance, and bridges the gap between solar projects that need funding, and lenders who want to finance them, expanding access to affordable solar energy.

- Chapter 1: Community Solar Regulatory and Market Context

- Chapter 2: Community Solar Project Site Selection

- Chapter 3: Community Solar and Community Engagement

- Chapter 4: Community Solar Development Process and Contracts

- Chapter 5: Community Solar Financial Modeling and Project Structuring

- Chapter 6: Community Solar Asset Management

- Chapter 7: Community Solar Business Structuring

Climate experts agree that in order to confront climate change we will need to scale many kinds of renewable energy projects to replace current fossil-fuel power generation. These projects will include utility-scale solar power plants, distributed solar installations, and community solar systems.

Besides the benefit of renewable energy generation, mission-driven community solar projects can provide additional benefits for subscribers. The National Community Solar Partnership (NCSP) has defined a set of “meaningful benefits” that equitable community solar projects should strive to provide (see below). NCSP aims for developers to include at least two of the five meaningful benefits in their community solar project development and deployment.

For more information on the benefits of equitable community solar projects, please see How Community Solar Benefits Communities. This workbook is specifically for individuals who are focused on building community solar that provides co-benefits to low-to-moderate income and disadvantaged communities. Refer to the DOE landing page regarding education and outreach around community solar.

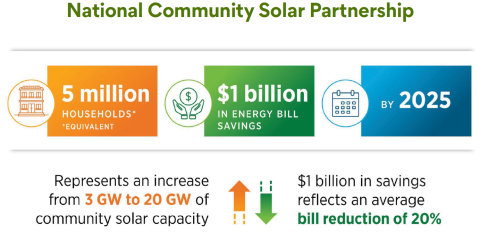

NCSP is a coalition of community solar stakeholders working to expand access to affordable community solar to every U.S. household and enable communities to realize other benefits, such as household energy bill savings, increased community and grid resilience and equitable workforce development. NCSP is led by the Department of Energy’s Solar Energy Technologies Office, in collaboration with the National Renewable Energy Laboratory and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Partners leverage peer networks and technical assistance resources to overcome barriers to expanding community solar access and benefits. NCSP is open to any individual or organization located in the United States with an interest in supporting equitable community solar development in the U.S. Partners span government, utility, non-profit, and for-profit sectors.

For more information on the National Community Solar Partnership and to stay up to date on the latest opportunities, please visit www.energy.gov/community-solar.

This Workbook was created by the University of New Hampshire (UNH) and Housing Sustainability Advisors (HSA). Housing Sustainability Advisors is a consulting group that works at the intersection of solar and affordable housing development. HSA partners with the solar industry and housing developers to finance and build new projects that provide substantial benefits to LMI communities, find new sources of financing to fill gaps, meet requirements, and realize real returns on investments. HSA also supports local, state, and federal government agencies in designing programs to drive energy upgrades into the complex financial structures of affordable housing.

The Carsey School of Public Policy at the University of New Hampshire is nationally recognized for its research, policy education, and civic engagement. The school takes on pressing public issues with unbiased, accessible, and rigorous research, builds the policy and political problem-solving skills of its students, and brings people together for thoughtful dialogue and practical problem-solving. The Carsey School Center for Impact Finance addresses the role access to capital plays in addressing income inequality and building a more sustainable future for communities.

This Workbook can be used as a stand-alone tool and also as a companion for the virtual course called the Community Power Accelerator Learning Lab. The Workbook and Course content were developed in collaboration with several national leaders in the community solar field. We would like to extend a sincere thank you to these organizations for sharing their knowledge with us and we encourage you to visit their websites, contact their teams, and support their work.

Are You Ready?

The primary audience for this Workbook includes individuals, non-profit organizations, cooperatives, and mission-driven for-profit companies with the capacity to invest substantial time to learn how to develop community solar projects that include the meaningful benefits listed earlier. Here are some examples of stakeholders who will find the information in this Workbook most helpful:

- Staff from non- and for-profit organizations with some project or real estate development experience, interested in expanding into developing LMI community solar;

- Individuals with some solar development or basic project finance knowledge that want to expand into LMI community solar development;

- Current solar developers seeking to expand into LMI community solar development;

- Staff from non-profit organizations that provide services to low-income households, with interest in expanding into LMI community solar development; and

- Organizations that own land and/or property, and are open to partnering with community solar developers, including the following types of organizations:

- Affordable housing developers

- Commercial land and real estate owners

- Non-profit organizations that own real estate, such as religious organizations, educational institutions, and farming cooperatives

- Government entities that own real estate

- Community organizations starting an energy cooperative to develop solar

This Workbook is intended to go beyond the basics of community solar and is targeted to those who already have a basic knowledge of what community solar is and how it works. If you need basic context to frame the more in-depth information that follows throughout the workbook, see the resources and videos on this page. To learn about the different ways to go solar, watch this video.

What is Community Solar?

The U.S. Department of Energy defines Community Solar as any solar project or purchasing program, within a geographic area, in which the benefits flow to multiple customers such as individuals, businesses, nonprofits, and other groups. In most cases, customers are benefitting from energy generated by solar panels at an off-site array. Community solar allows individuals or groups to buy or lease a share of a project and earn credits toward their electric bill based on the amount of electricity their share generates.

Community Solar provides a great option for those who face barriers installing solar panels on their own roofs, such as renters who do not own their homes, owners with insufficient roof conditions for solar panels, or owners who cannot afford the high upfront investment in solar. Community Solar installations offer the potential for an equitable transition to renewable energy by broadening the reach of solar participation. To learn more, watch this video on Community Solar basics.

Community solar business models vary based on state policy and available incentives. In states with enabling legislation for community solar, individuals, businesses, or organizations may buy or subscribe to a “share” in a community solar project. When you subscribe to a community solar project, you receive a credit on your electric bill each month. The size of your share and the energy generated by the solar array determine how much credit you receive. Solar United Neighbors (SUN), a non-profit community solar advocacy organization, provides an excellent webinar series about the basics of community solar, which can be found below:

- Episode 1, Community Solar Basics: Consumer Information

- Episode 2, Community Solar Policy and Programs

- Episode 3, Project Development: Grow Your Own

Why Now?

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) may be the most important pro-solar law Congress has ever passed. For prospective solar developers, the most important piece is the extension of the 30% federal Investment Tax Credit (ITC) for community solar projects. Starting in 2023, small community solar projects (under 1 MW) may qualify for a base ITC of 30% through 2033. These projects can also earn additional credits, such as:

- + 10% for meeting domestic content specifications,

- + 10% if at a brownfield site or in a community directly impacted by fossil fuels.

- + 10% if in a low-income community or on tribal land (by application) OR

- + 20% if part of a Low-Income Residential Building Project or Qualified Low-Income Economic Benefit Project (by application)

The Solar ITC credit, along with the 20% bonus for qualified low-income economic benefit projects, is a game-changer that will be especially helpful for developing small-scale, equity-focused community solar. Larger community solar projects can also qualify for the tax credits above; however, these credits will only apply at the same levels if larger projects also meet certain labor and workforce development requirements.

Beyond the extension of the ITC and additional bonus credits, the IRA contains many further provisions and funding mechanisms that will help communities go solar and convert to clean energy technologies. For a broad overview of the IRA, the Department of Energy provides further details here. For those interested in specific details on IRA incentives for affordable housing, Novogradac provides a high- quality overview here.

This Workbook is focused on equitable community solar. Equitable community solar is defined as projects that provide access to solar energy for people from all walks of life, including low-income and underserved communities, and that seek to create meaningful benefits for participants such as creating and supporting quality jobs, saving money, supporting community ownership and wealth-building, and providing energy resilience through distributed generation.

This Workbook helps community solar developers integrate equity considerations throughout the development process, including the NCSP’s meaningful benefits. If approached intentionally, community solar can serve as a very effective tool for achieving equity goals. Groundswell recently created an overview of the components of equity within the context of community solar development, which can be found here.

“Eyes on Equity” sections are included in each chapter of this Workbook. In each, you will find tools, resources, and information that you can use to create a community solar project that prioritizes equity

Low-to-Moderate Income (LMI)

A low-income household is one in which the resident’s total annual household income is 50% or less of the area median income (AMI) of where they live. A moderate-income household is one whose total annual household income is above 50% and less than 80% of their AMI. Therefore, households under 80% AMI can be identified as LMI. Neighborhoods and geographic areas can also be defined as LMI according to the percentage of people living there who meet the low- or moderate-income definitions. Due to the definition, a household considered LMI in one location, may not be considered so in another with a lower median income.

Energy Justice

The Initiative for Energy Justice defines Energy Justice as “the goal of achieving equity in both the social and economic participation in the energy system, while also remediating social, economic, and health burdens on those historically harmed by the energy system (“frontline communities”). Energy justice explicitly centers the concerns of marginalized communities and aims to make energy more accessible, affordable, clean, and democratically managed for all communities.” To learn more about Energy Justice, visit the Initiative for Energy Justice.

Environmental Justice (EJ)

The EPA defines environmental justice as "the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies." The Department of Energy (DOE) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) both currently have EJ-focused programs such as the Justice40 Initiative. The DOE conducts regular stakeholder engagement with communities and integrates EJ considerations into its programs, and the EPA facilitates collaborative partnerships and awards EJ-focused grants.

Energy Burden

A household’s energy burden is the proportion of annual household income spent on home energy

costs annually, which can include electricity, heating fuel, and at times, transportation costs. Historically, low-income, Black, Latinx, and Native American households, as well as multifamily and renter households, have higher energy burdens than other households. The Department of Energy’s Low-Income Energy Affordability Data (LEAD) Tool and the Climate and Economic Justice (CEJST) Tool allows users to explore which areas have the highest energy burden. Targeting clean energy investments to communities with higher energy burdens can help remediate inequities in our energy system.

For further information on the benefits of community solar, watch this video: How Community Solar benefits communities.

A Best Practices Guide on developing solar with meaningful benefits, visit online here.

Workbook Structure

The Workbook is organized to present preparatory content, including the Community Solar Self-Assessment and Initial Project Readiness test followed by the seven chapters below:

Community Solar Self-Assessment: Self-Assessment Tool

Project Readiness Test: Community Solar Project Readiness Framework;

Chapter 1: Community Solar Regulatory & Market Context

Chapter 2: Community Solar Project Site Selection

Chapter 3: Community Solar & Community Engagement

Chapter 4: Community Solar Development Process & Contracts

Chapter 5: Community Solar Financial Modeling & Project Structuring

Chapter 6: Community Solar Asset Management & Operations

Chapter 7: Community Solar Business Structuring

Each Chapter Is Structured in the Following Manner

Project Readiness Questions

The intention of the project readiness questions used to introduce each chapter is to provide questions the reader should consider throughout the chapter’s material and should be able to answer after completing the chapter. The questions in the Project Readiness sections coordinate with and expand upon the Credit Ready Checklist, which is a comprehensive tool that enables an organization to determine whether it has prepared all the necessary information to present its community solar project proposal to potential investors and lenders.

Background

This section offers background for the information to follow, sets the context for the material, and provides the details necessary to complete the Action Items.

Eyes on Equity

The Eyes on Equity Boxes present resources and best practices to ensure developers stay on track to reach LMI communities and achieve NCSP’s meaningful benefits.

Additional Resources

This Additional Resources provides additional readings, best practices, and tools for readers to further expand their knowledge of community solar development.

Are You and Your Organization Ready to Develop Community Solar?

Before you go any further into this Workbook, you should spend some time to reflect on whether you and your organization are ready to develop community solar. Solar project finance and development is complex, and learning how to do it will require a substantial investment of your time and resources. Organizations with pre-existing experience in project development, finance, real estate, and service to low- income communities have significant advantages to succeeding in low-income community solar development.

The first step in determining your readiness for community solar development is to assess your existing experience in related fields, you and/or your organization’s financial assets, and your risk tolerance. Unlike, for example, the medical field, where you must earn highly-specialized credentials to practice professionally, no credentials are required to develop community solar. Anyone can start developing a community solar project, yet those who are most prepared have the highest likelihood of achieving success.

Self-Assessment Tool

As you consider the path to becoming a community solar developer, those with the skills and experience below will have an advantage. If you are not already a community solar developer, think about whether your organization has the kind of experience or assets in any of the following areas. Organizations that are strong in any one of these areas can play very important roles in the community solar development process.

Project Developers & Operators

Those that already have some experience in any other real estate or equipment financing have the easiest time learning the skills required to develop community solar.

Property Owners

Solar developers must compete for sites against all other potential land uses. Typically, when a property owner decides to develop any site, their most valuable and first option is some form of real estate, followed by a parking lot. Because solar is not as competitive a land use choice as real estate or parking, it can be challenging to find sites for solar installations. Community solar developers must be thoughtful about the different development priorities of real estate owners and where solar fits in. For this reason, those organizations with property that they are willing to use for solar have the most substantial advantage in community solar development. Even if the property owners are not knowledgeable about the solar industry, they can partner with experienced solar developers who are searching for partners who own property.

Asset Owners

The solar development process requires a substantial amount of capital. Even if an organization is able to borrow the majority of a solar installation cost, lenders will always require a sponsor to invest or provide collateral in the project. Lenders will also require cash or other assets to be provided to secure loans. Cash will also be required from a developer at the very early stages of a project, also called Pre- development funding. As such, those organizations with other assets and cash on-hand have a huge advantage to access additional lending and project finance opportunities.

Low-Income Service Providers

Those organizations that already serve low-income households have the most accessibility to potential low-income community solar subscribers. They understand the unique challenges and costs of providing services and products to this population and can help to build trust with households who may have been impacted negatively by the energy sector in the past. They can also support equitable community engagement to ensure that communities support the development of community solar locally and help to raise awareness and enroll prospective subscribers within LMI communities.

Large-Scale Electric Commercial Customers

Those commercial businesses or organizations that require electric power, especially with substantial high electric demand, have the opportunity to serve as an “anchor tenant” or “anchor subscribers” (key customers). This allows large organizations to subscribe to a significant portion of the energy produced by a project which can provide certainty and reduce risk for developers. These organizations can provide a reliable source of revenue and potentially serve as a host location for a community solar project.

The Community Solar Developer Evaluation tests your organization’s readiness by exploring your skills and experience in the areas above. Your answers will determine if this course is right for you and, if it is, which approach you should take to the rest of this Workbook. Once you answer the questions, the tool will provide you a “Readiness Score” from 0 to 300, with 0 being the least advantaged starting place for being a community solar developer and 300 being the most advantaged.

In addition, you may consider using the Department of Housing and Urban Development Organizational Solar Readiness Tool to evaluate your organization’s current understanding of opportunities for solar

Getting your organization ready to answer this question is the most important goal of this Workbook. The Workbook seeks to help aspiring community solar developers to prepare all necessary information so that they are ready to present their community solar project proposals to investors and lenders. As a result, lessons in project readiness are integrated throughout this Workbook, with exercises aimed at teaching you to pitch your community solar project to a potential investor or lender.

Before a community solar project can be developed, financing for the project needs to be secured, which includes predevelopment, construction, and permanent financing sources. Funders are lenders, investors, philanthropic organizations or government entities that provide capital, debt or equity to a project. Because funders have such a high bar to earn funding, they often push developers the hardest to solve the tough questions about their projects and ensure projects are feasible.

As such, it is helpful to consider project readiness through the lens of capital providers. The analysis of projects by Funders falls into the following categories:

Local Regulations and Policies

The first question all community solar developers must answer is whether the type of community solar project that you are proposing is legal and possible within your state and local jurisdiction. Funders will assess the regulatory environment and local policies regarding community solar projects such as community solar enabling legislation, net metering laws, building codes, zoning requirements, fire codes, permitting issues, tax incentives, and interconnection rules to determine project feasibility. They will look at the status of any required government and utility permits for the project, especially “interconnection permits,” which give permissions from local utilities for solar projects to connect to transmission infrastructure.

Site Control

Funders will analyze whether you have some type of “site control.” In other words, they will want to know if you either own the land or building where the project will be developed, or if you have an agreement in place with the owner to develop the project.

Project Performance

Key factors that drive project performance include location, equipment selection, and installation plan. Project developers will model the location-specific energy generation potential based on average annual solar radiation, shading patterns, installation orientation, and equipment selection. Funders will assess this modeled generation potential as it relates to anticipated project revenues.

Financial Feasibility

Funders will perform analysis to ensure that a project has a reasonable return on investment, both for their investment and other invested parties. The financial feasibility of the project is critical for repayment of and return on their investment. They will closely analyze upfront costs and sources, operating costs and potential revenue, and evaluate overall project risks. Developers must demonstrate that all parties can make reasonable returns and that the project plan includes a cushion, or room within profit margins that accounts for the chance that an outcome or investment’s actual gains will differ from an expected outcome or return.

Financial and Performance Risks

Funders will carefully evaluate the risks of investing in the project, such as regulatory or environmental issues, and weigh these against the expected returns on the investment.

Development team

Funders will assess the development team’s expertise and experience. They will evaluate the team’s ability to manage the project, including their track record of delivering similar projects on time and within budget.

Community Engagement

Community solar projects may face opposition from the local community so investors will want to assess the level of community engagement and support for the project. They will examine factors such as the level of authentic community involvement in the project’s planning, the benefits the project will deliver, and the local community’s willingness to support and/or participate in the project.

The Credit-Ready Checklist, developed by the Community Power Accelerator team, with input from funders and philanthropy, is the key resource that developers may use to ensure their projects are ready to shop around to Funders. Lenders, philanthropic organizations, and developers will know that a project is ready for them to begin initial funding conversations if the checklist is completed for a community solar project. The checklist contains nearly 50 important pre-development considerations, such as information about system size, siting, ownership, capital structure, revenues, and costs. It was developed in collaboration with over 40 representatives from financial institutions familiar with solar lending, including commercial banks, community development financial institutions, green banks, and credit unions. Community solar developers can answer the questions on the checklist with the help of technical support and resources provided through the Community Power Accelerator.